In Cleveland, Ohio in 1993, the J C Smith funeral home had recently closed and was being cleared. When the cleaning workers emptied the funeral parlor’s dark basement, a mummified body was discovered, which shed light on a lost, tragic tale from 19th century Queensland. The discovery finally gave closure to a group of indigenous Australians and provided long-awaited answers to a mystery from their past.

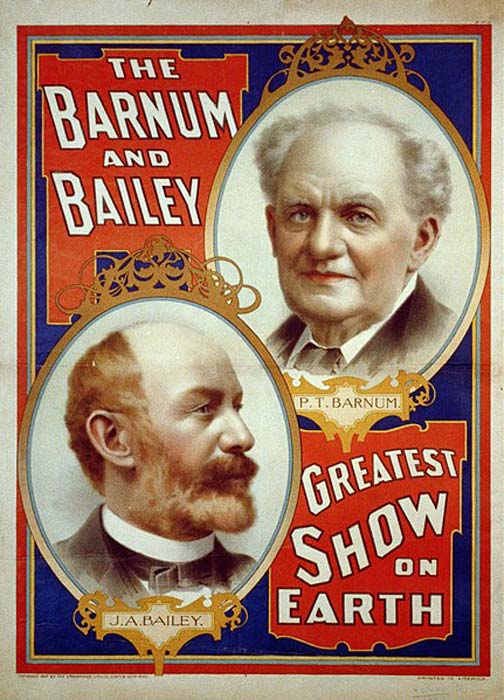

The mummified body was that of an Aboriginal Australian man and was found to be the once-famous “Tambo”. In the 1880s, Tambo, along with his wife and 15 other indigenous people, was recruited as a star attraction by Phineas Taylor “P T” Barnum and James Anthony Bailey as part of Barnum & Bailey Circus. He was exhibited as part of the “human oddities” in the Circus’s dime museum (named for the price of entry), which had been displaying “Freak Shows” since the first half of the 19th century. Barnum is popularly considered a pioneer of such attractions.

Colonialism and the Narrative of Western Superiority

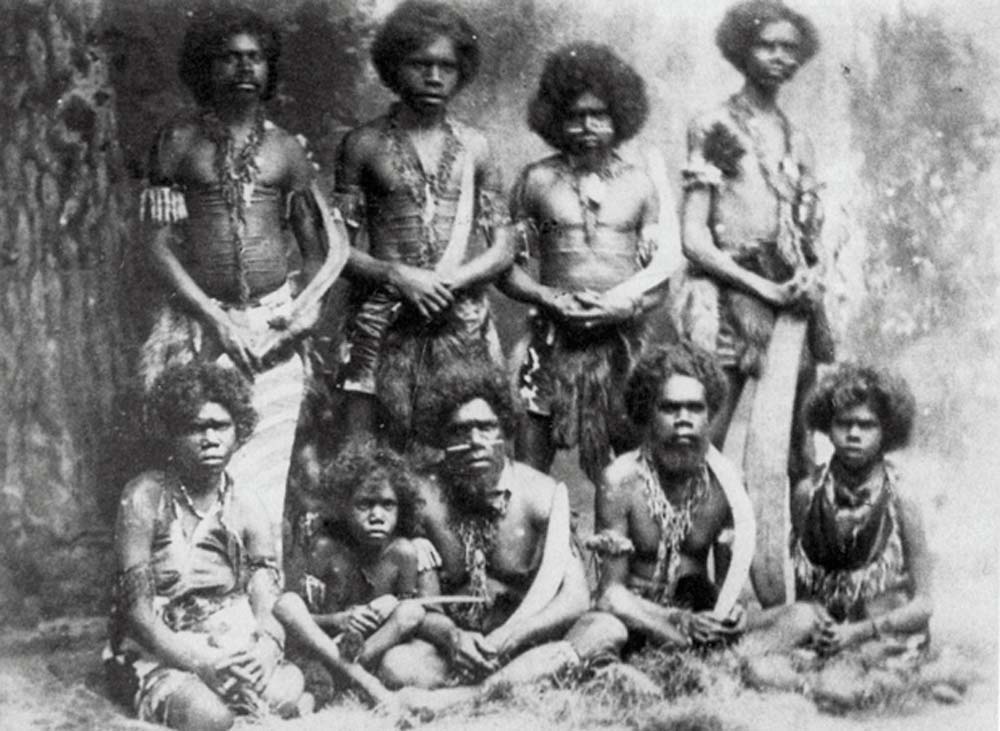

The 19th century saw a vast colonial expansion from the European powers across the globe. One of the domestic impacts of such expansion was a growing curiosity among the Western public to view examples of the cultures and unfamiliar peoples subjugated by this expansion. Examples of indigenous people with strikingly different appearances to Westerners were seen as part of the phenomena of “humans with oddities”. They were paraded in such circuses as Barnum & Bailey’s as examples of European colonizing triumphs against societies perceived as less advanced.

Indigenous Australians, c1904 (hwmobs / Flickr)

Indigenous people’s features and body proportions were unfavorably compared with the anatomy and morphology of Europeans. This created an erroneous and self-serving narrative regarding the superiority of the Western nations over other peoples, often depicted as savages. 19th century forefather of modern anthropology Johann Friedrich Blumenbach had gone further in casting Western man as the ideal for civilizational advancement. He claimed Westerners belonged to the Caucasian race, which was considered superior in comparison to other races because of its supposed corporeal harmony and aesthetic beauty.

On the Origin of “Freak Shows”

With the dawn of Enlightenment, anthropological science sparked a great deal of curiosity regarding the unfamiliar appearances of indigenous humans from around the globe. As the market expanded and people’s fascination for travel and science grew, “Freak Shows” exhibiting such peoples appeared to take advantage of this craze for “Orientalism”. These started in the zoological gardens and parks in 18th and 19th century Europe, where indigenous non-European people were displayed as exotic attractions, at a time when people’s interests in the more familiar zoological exhibits was in decline.

Barnum and Bailey advertised their circus as the “Greatest Show on Earth” (Library of Congress, Public domain)

By the first half of the 19th century, these exhibitions expanded to become part of circuses, dedicated exotic communities, wax figure museums, anatomy museums, fairs and “Cabinets of Curiosities”. 19th century evolution theory was co-opted in a nakedly chauvinist fashion, dividing the world outside of Europe into colonies of “savages”. Indigenous tribes like the Zulu, Khoikhoi, San people or the Aboriginal Australians were seen as physically anomalous humans and commonly compared to monsters, or animals. One of the most notorious early fairs, Bartholomew Fair, was described as a “Parliament of Monsters” by William Wordsworth.

The customs of such indigenous groups were also showcased to Western audiences as examples of technologically primitive cultures. Such representations further legitimized Western society’s colonialist expansion and their sense of cultural superiority. The dehumanizing nature of these “Freak Shows” created a fictional and self-aggrandizing hierarchy for Western audiences, implying that such expansionism and subjugation were natural and appropriate behaviors. These exhibitions remained culturally relevant until the collapse of the colonial empires in the mid-20th century.

Julia Pastrana from Mexico hairy woman. Date: circa 1850. Source: Archivist / Adobe Stock

Barnum and his “Human Circus of Oddities”

P T Barnum was a leading pioneer of these “Freak shows”. Barnum ventured into this industry in 1835, when he showcased a paralyzed slave he owned named Joice Heth. Although she was around 80 years old, Barnum advertised her as George Washington’s 161-year-old nurse. He exhibited her across the northeast of America until her death 1836, after which he made arrangements for Heth’s public dissection in pursuit of further profits.

There were popular claims at the time that Barnum had starved Heth while she was alive and forcibly removed her teeth to make her look older. These stories made their way into the penny press, but in spite of this (or possibly because of the notoriety that came with such stories) “Freak Shows” continued to gain popularity.

After 1841, Barnum reinvented his dime museum into a place of wonders, with these “Freak Shows” being the central attraction, broadly targeting a family audience. The “Freaks” were divided by Barnum into three categories – “born freaks” such as overweight ladies, dwarfs, “skeleton men” and giants; “exotic freaks” from indigenous cultures; and “self-made freaks”, for example those who performed novelty acts and heavily tattooed men. This again proved immensely popular and further cemented the reputation of Barnum as the “greatest freak showman”.

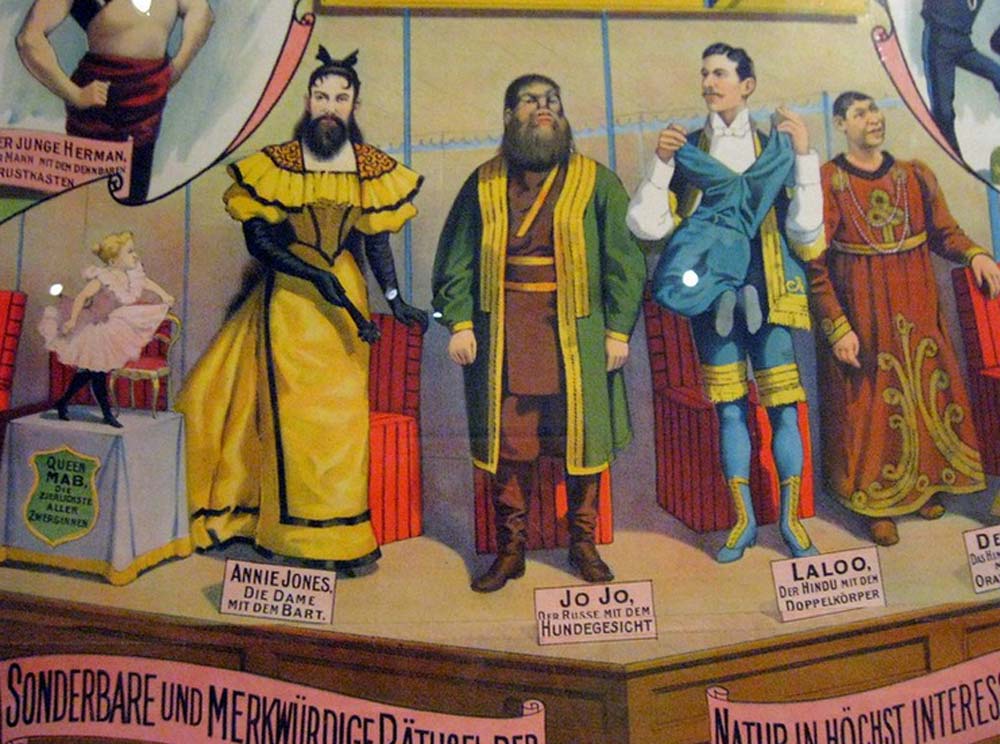

Barnum & Bailey’s circus on tour in Germany (elycefeliz / Flickr)

With the popularization of “Freak Shows”, any examples of physical difference from European racial norms were displayed for public consumption by Western audiences. In the 19th century, a Khoisan woman named Saartjie Baartman, who was bought as a slave by British doctor William Dunlop in 1810, was given the name Hottentot Venus and was displayed in the marketplace and circuses under humiliating conditions, till her death in 1815.

Amongst the attractions displayed by Barnum, Charles Sherwood Stratton, a dwarf, became a star of the show under the stage name ‘General Tom Thumb’. His act included dancing, singing, jokes, as well as imitating mythological and historical people such as Hercules, Cupid, Samson or Napoleon Bonaparte.

Other oddities who gained popularity through Barnum’s “Freak Shows” were Bartola Velasquez and Maximo Valdez Nunez, known as “The Last of the Ancient Aztecs” or the “Aztec Children”, conjoined twins Chang and Eng who were known as the “Siamese Twins” and performed somersaults and acrobatics, and Annie Jones who was showcased as the “Bearded Girl” or “Bearded Lady”.

Tambo’s Recruitment

The story of Tambo, whose mummy was rediscovered in 1993, and his miseries in this circus began over a century earlier in the year 1883. Robert A Cunningham, a recruiter working for Barnum and Bailey’s circus, had travelled to Hinchinbrook and Palm islands, located in the far north of Queensland, to find new attractions for the next exhibition, to be titled “Ethnological Congress of Strange Tribes”.

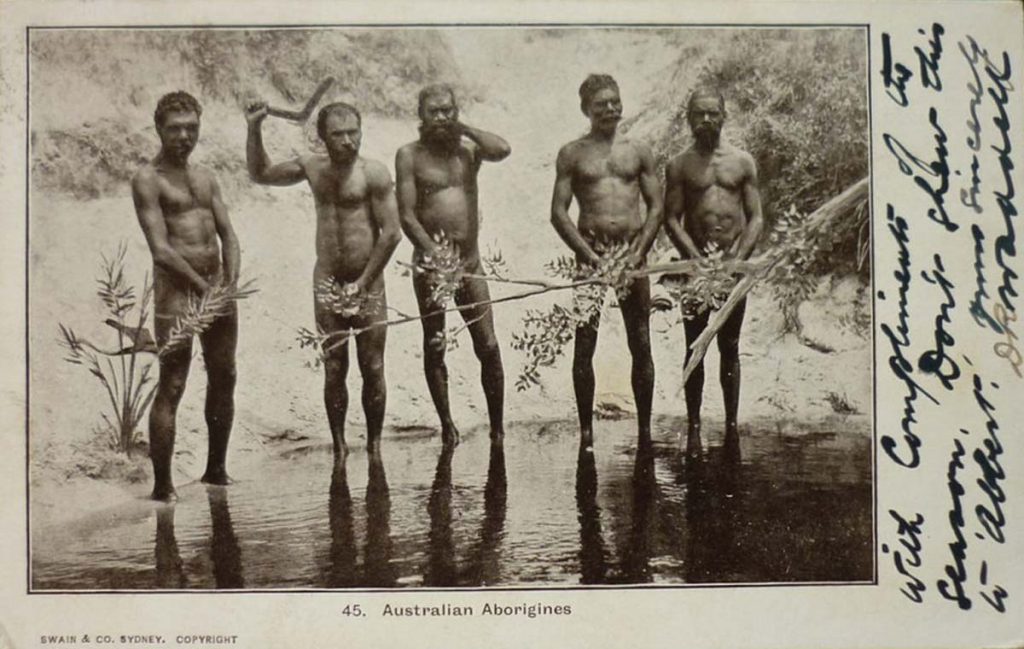

Cunningham’s Aboriginal Circus, including Tambo (believed sitting, second from right) (Unknown Author, Public domain)

Cunningham was looking to add various indigenous people to the collection, which already featured southern Egypt’s Nubians, southern India’s Toda, Africa’s Zulus, and the USA’s Sioux. The Australian Aboriginal tribes were a new addition.

It is not certain how these people were persuaded or forced by Cunningham to join the exhibition, but according to the records, six men and two women from the Aboriginal tribe, as well as a boy belonging to the Wulguru clan, joined the troupe of Barnum and Bailey’s circus and left for Chicago from Palm Island and Hinchinbrook by ship in the year 1883. It is today believed that the people of the Aboriginal tribe were either tricked by Cunningham or given incentives like the promise of adventure, or expensive clothing.

University College London’s honorary research fellow and anthropologist Roslyn Poignant, in her book Professional Savages: Captive Lives and Western Spectacle, writes that chief among the reasons for indigenous people joining the troupe were “Displacement and dispossession in the colonies, chance and curiosity”. According to records from the time, only two members of the group knew the English language. While their records indicate that they went willingly along with Cunningham, it is unclear that any of the people recruited in such fashion truly understood to what they were agreeing.

Lies and Showmanship

These men and women were presented as “Australian Cannibal Boomerang Throwers” by Barnum, ignoring that boomerangs were not used by any of the indigenous people as their “chief weapon of warfare”, as Barnum had advertised. Philip Rang, an Australian cinematographer speaking to BuzzFeed News, noted that the indigenous Australians became “the drawcard” for world exhibitions and these “Freak Shows”. “The Aboriginal groups were considered as boomerang-throwing cannibals, even though Aboriginal people weren’t cannibals,” he said.

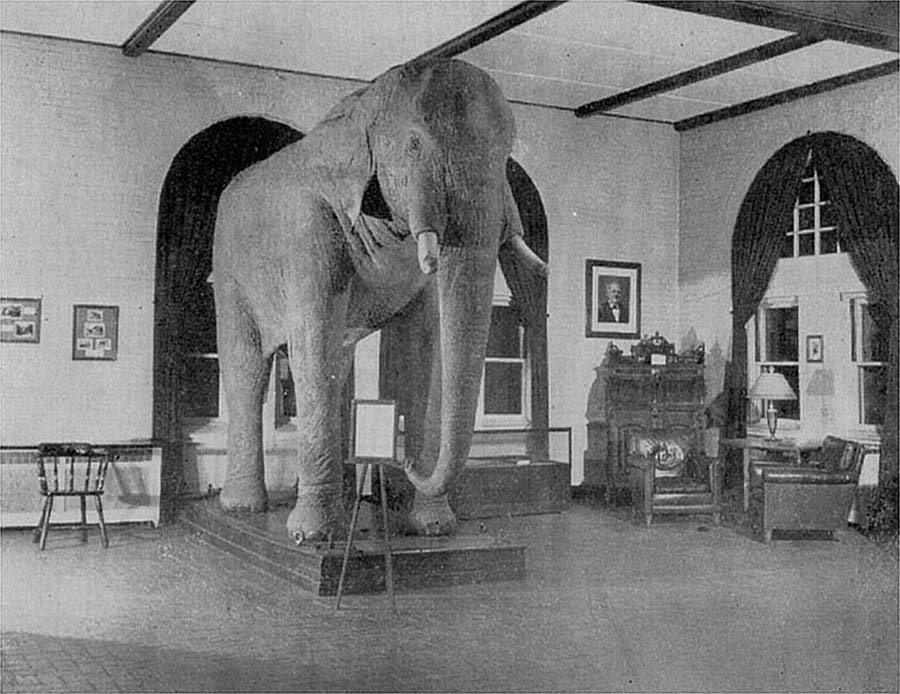

Jumbo was stuffed after his death as an attraction (Barnum Museum of Natural History, Public domain)

These “Australian cannibals”, as promoted by Barnum, were made to sing, dance and throw boomerangs alongside an elephant named Jumbo, for the amusement of the crowds. On the first day of the show in Chicago, more than 30,000 people came to see the performances of these “Australian savages”. Such spectacles were dehumanizing in the extreme. One of the descendants of Tambo, Jacob Cassady, said, “I think it would have been the most horrific experience. They wouldn’t have even known what an elephant was. And they would have been missing their family and were unable to carry out traditional ceremonies.”

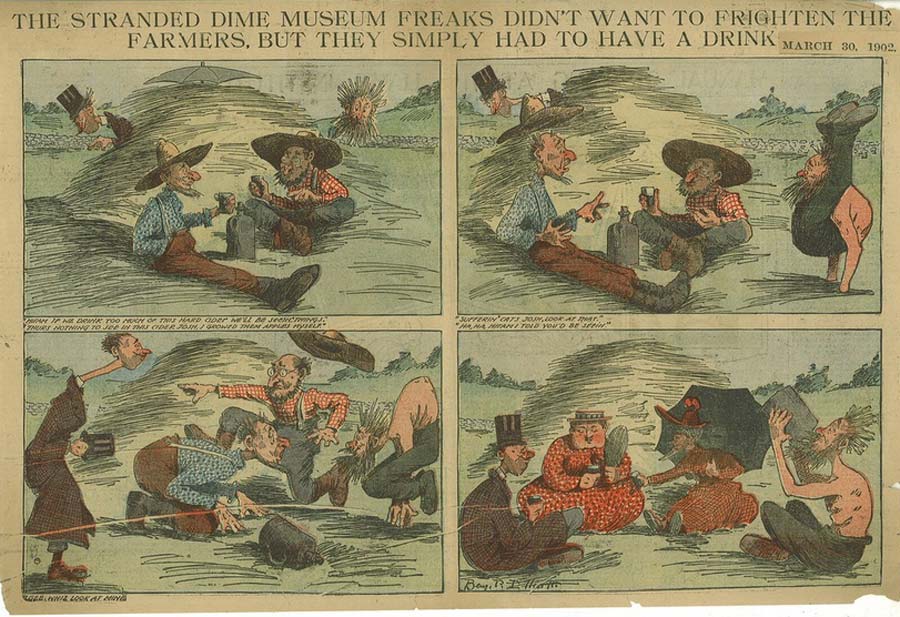

Cassady is the owner of a small museum on Aboriginal history and culture in Mungalla Station in Queensland, which has an exhibition space where the stories of these men and women were put on display. As per Cassady, the Aboriginal people were measured by anthropologists and posed for photographs in Western clothing, as they toured from the US to Europe to Russia. These indigenous groups, as part of Barnum’s troupe, were also allowed by Barnum to visit fairs and dime museums in the USA. These were known for providing “edutainment”, referring to moral education and entertainment for the working class.

Typical dime museum advert, 1902 (stwalley / Flickr)

Walter Palm Island, a descendant of Tambo speaking to BuzzFeed News, noted of Tambo and the troupe “It was very degrading the things he (Tambo) had to do. I look at those old people in those photos and look at the expressions and I see the suffering. I can see the sadness in their face because of being away from country and being overseas in a foreign land and feeling out of place,”

Virtual Prisoners

There is evidence that some freedom and money were granted to these Aboriginal people after the performance season had ended. However, the tribal people were heavily reliant on Cunningham for shelter, medical care and food. The medical care provided was often insufficient and led to most of the troupe dying of pneumonia, as they failed to acclimatize to the cold conditions of the northern hemisphere. The first person to succumb to pneumonia in the troupe was Tambo.

The sources suggest that Tambo died just a year after he left his home. However, the injustice and atrocities these men and women were subjected to did not stop with their deaths. Cunningham and Barnum intended the dead body of Tambo to be placed permanently on display for the general public. And hence, before his relatives could complete any traditional rituals, his body was embalmed and displayed in a dime museum.

Cultural Theft and a Legacy of Shame

As Poignant notes, “He was subjected to a final, terrible indignity. His embalmed body was placed on show in Drew’s Dime Museum, and it remained on display there and elsewhere in Cleveland until well into the 20th century.”

After laying forgotten in the basement of a funeral home until 1993, his dead body was finally rediscovered and repatriated to Palm Island where his relatives were finally able to perform their customary funerary rituals, 110 years after Tambo breathed his last breath.

Remembering what he was told as a child, Cassady says, “I remember Granddad Wally [Walter Palm Island] telling me when he was a kid that some relations were taken away to the circus, but I thought…the story was a bit romanticized. But the more I heard about the story, the more I learnt about it, and the more amazed I was. It thought it was unbelievable.”

These “Freak Shows” gradually passed out of public favor in the first half of the 20th century with the rise in popularity of cinema, and an increase in international tourism after the Second World War. With the passage of more than half a century the truth of such exhibitions has faded from current public awareness, and there is a risk that the gross exploitation of such attractions might be whitewashed with the kind of entertainment offered by modern Hollywood blockbusters. This does disservice to the brutal mistreatment, suffering and abuse of indigenous peoples around the globe at the hands of exploitative entrepreneurs such as P T Barnum, “The Greatest Showman”.

Top Image: Human ‘strongman’ in a circus cage. Source: Pavel Losevsky / Adobe Stock

By Prisha