History at its most dynamic is little more than a series of turning points. Key decisions, key marriages or deaths, and key battles often have the greatest impact, for it is here that we see how things could have been, and we gain an understanding of the sheer chance involved in creating the world we live in today.

One such turning point was the Battle of Culloden on 16 April 1746, the last pitched battle ever fought on British soil. The battle took place in Scotland, on Drummossie moor overlooking Inverness in the far north.

On this battlefield kings were chosen, and it was here that the dreams of the Jacobites and their attempts to restore the throne of the Britain to the successors of James II died. Nothing less than the British royal family and the religious future of the British Isles was decided here.

So who fought at Culloden? And what was won, and lost there?

Bonnie Prince Charlie

Charles Edward Louis John Casimir Sylvester Severino Maria Stuart was born on 20 December 1720, the first of two sons born to James Francis Edward Stuart. James and his family were living in Rome, where Pope Clement XI had given his father residence, and had been known as the “Old Pretender” amongst friends and enemies. Many saw him as the legitimate king of England.

For James was the grandson of James II (and VII of Scotland), who had died in 1701. Some sixteen years before that point, James II had been deposed by his aristocracy and the Parliament of Britain and replaced by a preferred Protestant Dutch noble, William of Orange, in what was called the “Glorious Revolution”.

Many who looked on were shocked at James’s overthrow, and considered him the legitimate king. After his death his son James was also considered king, and when he died in 1766, Charles was considered to have inherited the crown as Charles III.

During his lifetime, he was known by many names among his supporters who were largely Scottish and French, ever the enemies of England. He was known as “the Young Pretender” and “the Young Chevalier” but he was most commonly known as “Bonnie Prince Charlie”.

In Rome, Charles Edward was introduced to Italian society. In 1737 James had sent his son on a tour through the main Italian cities. He wanted his son to complete his education as a prince and man of the world.

He was received with distinction on his journey and he was showed how respected the exiled house was by the Catholic powers of Europe, as well as explaining Britain’s concerns regarding its fortunes. His father had planned to rely on foreign aid in his attempts of restoring himself to the British and Irish thrones.

It was important to create in Charles some suitably educated, refined and well informed who could rally such support from abroad. Charles was being made into the very model of a king.

But the key moment in Bonnie Prince Charlie’s life did not occur when he was considered king in exile. It happened while his father still lived, and when, for a brief moment in the 1740s, it seemed that he would win back his crown.

The Battle of Culloden

In 1743, James named his son Charles as “Prince Regent”, effectively resigning his claim to the crown in favor of the Young Pretender. This was a shrewd move, allowing sympathetic elements to unite behind this young man. Furthermore Charles was no inexperienced leader, having been appointed general of artillery and observing the French and Spanish siege of Gaeta, his first taste of war.

Buoyed by this, Charles’s father managed to obtain the renewed support of the French Government in 1744, at which point Charles traveled to France with the sole purpose of commanding a French army that he would lead in an invasion of England. The invasion never materialized, as a storm scattered the invasion fleet and the moment was lost.

Now facing certain defeat if he attempted an invasion across the Channel from France, Charles tried a different approach. Travelling to Scotland, he raised an army there with the support of the Scottsh nobles and marched on Edinburgh.

After a victory at the Battle of Prestopans, Charlie marched south into England at the head of 6,000 men. However here he made his first mistake, in turning back to Scotland after his nobles counselled caution and feared for the lack of local support.

Although this army won another battle on their return to Scotland at Falkirk, the situation remained unimproved and the British were gaining ground, having reorganized their army under the Duke of Cumberland, son of the British monarch George II.

- How the Darien Scheme Changed the History of Scotland’s Independence

- The Lost Dauphin: What Happened to Louis XVII?

Charlie and the Jacobite leadership had few options left other than to stand and fight. The two armies eventually met at Culloden, on terrain that gave Cumberland’s larger, more well-rested force the advantage.

Charles had decided to form his army across from the British cannon, assuming that the enemy would charge first. He realized his mistake and saw how exposed his troops were, but the messenger he sent with new orders never made it and his army was annihilated by the cannon fire.

The battle was over in only an hour. As the smoke cleared, between 1,500 and 2,000 Jacobites were killed or wounded, while the loyalist army had only lost some 300 soldiers. But this defeat was the end for the Jacobite uprising: while as many as 6,000 Jacobites remained in arms in Scotland, the leadership decided to disperse, effectively ending the rising.

Charles himself was lucky to escape the battle and the roving bands of British soldiers who hunted for him afterwards. After a desperate flight across Scotland he finally gave the authorities the slip and returned to France by ship. Not one of the Scotsmen who assisted him ever considered the £30,000 reward for his capture.

A Turning Point in History?

The Battle of Culloden can be considered a genuine and serious attempt by the Jacobites to restore the Catholic dynasty of James Stuart to the British throne. Had Bonnie Prince Charlie defeated the British forces at Culloden, or had he continued his attack into England, our past could have been very different.

As it was, this was the end of the Jacobite rebellion in earnestness. The British Government enacted laws further to integrate Scotland into Great Britain, laws which were explicitly valid in the Scottish Highlands as with the rest of Britain. Charles himself died in 1788 without ever again seriously attempting to claim the throne.

The members of the Scottish Episcopal clergy were required to give oaths of allegiance to the reigning Hanoverian dynasty of Great Britain, and much of Scotland’s independence and separate identity were lost. Charles himself remained in exile for the rest of his life.

However, had he won, Scotland, Britain and Europe could have been very different indeed.

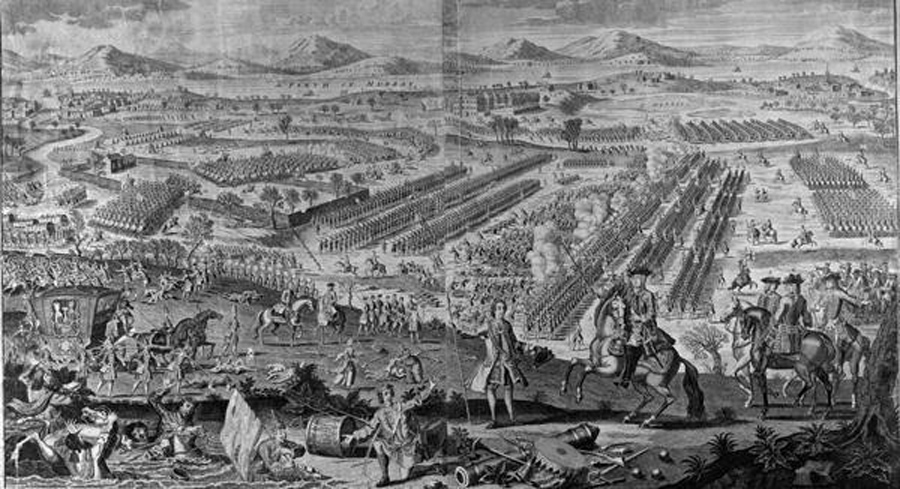

Top Image: The Battle of Culloden. Source: David Morier / Public Domain.

By Bipin Dimri