The start of the 8th century was a golden age for Islamic expansionism in Europe. The new religion of Mohammed and his followers swept across the Middle East, north Africa and into southern Spain, and it looked for a moment as if the armies of the Umayyads of Damascus might overrun Europe entirely.

We have already covered the Battle of Guadalete, where the Muslim invaders of Spain overran and defeated the Christian Visigoths and established themselves in western Europe. But this was far from the end of their ambitions, and the armies of the caliphate marched northwards, across Spain and into France.

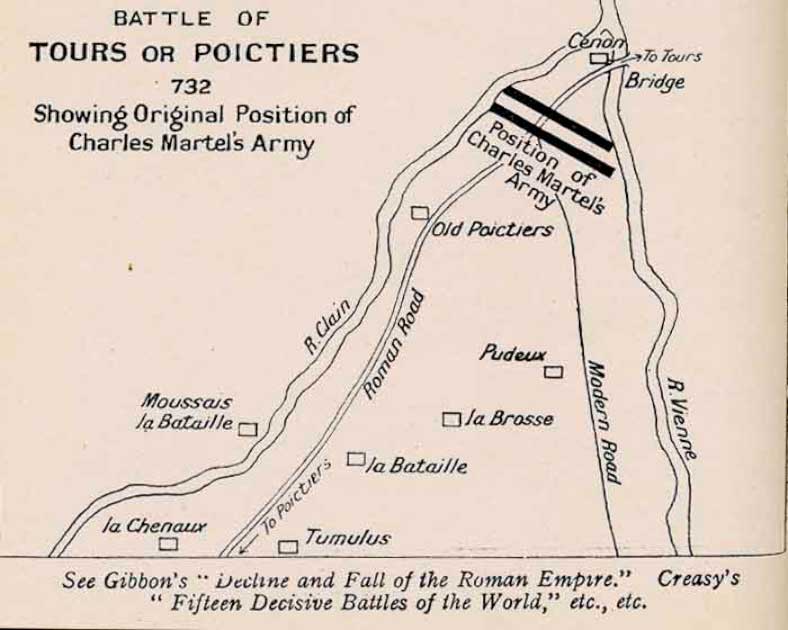

Europe seemed destined to fall to Islam. It was only at the Battle of Tours, in 732 and after twenty years of fighting the Muslim armies, that they were finally halted.

The High Water Mark

On October 10, 732, the leader of the Franks, Charles Martel and his followers met the Islamic army of Emir Abdul Rahman Al Ghafiqi Abd al Rahman near the city of Tours in France. During the battle, the Frankish army defeated the invading Islamic army, and their leader was killed.

The Battle of Tours is therefore seen as an important battle which stopped the progress of Islamic invaders into Europe and preserved Christianity. As Islamic conquests stopped in the European region, Christianity grew in influence in France, Italy and other European countries.

The effort to defeat the Islamic army and stop the conquests was important because the Islamic people were already controlling the Persian Empire and the Old Roman Empire. If they had not been defeated at the Battle of Tours, the influence of Islam would have threatened other established empires and religious institutions in Europe.

The army of the Franks raised to face the Muslim threat was claimed to be enormous. The army’s numbers are recorded to be around 75,000 people but more recent revisions suggest a more modest force of maybe 20,000 soldiers.

- The Battle of Guadalete: How Islam Fought its way into Spain

- Alesia! The Lost Battle and the Roman Conquest of Gaul

The number of Muslims who fought under Abd er Rahman is also uncertain, but the contemporary Christian estimates of 60,000 to 400,000 soldiers seem wildly high. Most likely both sides were evenly matched with the same number of troops.

Moreover, much of the Islamic army was occupied in breaking up into smaller parties to carry out raids and pillaging campaigns of the houses and cultural centers of the Franks. Thus, the actual estimate of the Islamic army is difficult to put down.

However, according to historical accounts, the entire core army of the Muslims was present in the Battle of Tours. The defeat by the Franks, with Christian losses of only 1,500 (according to St. Dennis) was the end of their push northwards.

There are further confusion accounts as to the total number of troops. According to historical texts, the Islamic army waited for six days before the battle started, and during this time, the leaders were able to recalled all parts of their army. It is possible that the Muslim generals themselves did not know how many troops they had amassed.

The Muslims of Northern Spain had taken over Septimania by this time and settled down at Narbonne in southern France, which they called Arbuna. The Muslims were at their peak of power at this time and quickly pacified the nearby territories.

The Muslims threatened the Frankish territories, and the conflict continued for many years. But the Christians hoped that the tide was turning. Before the Battle of Tours, the Frankish people also fought the Battle of Toulouse, and while they were victorious this was not the knock-out blow they were looking for.

The Battle of Tours

As the Muslims pushed into Gaul they faced the Franks in the full might, the most powerful Christian military in Europe. The Muslims were confident: they had swept across much on the known world and, after all, they were convinced they had God on their side.

But the Franks controlled lands across modern France, Germany, Belgium and the Netherlands and were developing into the first European imperial state since the Western Roman Empire. The Muslim threat brought even more soldiers to their banner, as the Frankish realm emerged as a vast conglomerate standing against the Umayyads.

It seems the Muslim overconfidence played a significant part in their fall. The army had advanced into Gaul rapidly, outstripping their supply chain, and it seems the Muslim commanders were not anticipating that they would encounter a large army in their path.

For seven days the armies refused to engage in force, and although there were multiple minor battles between outriders and scouting forces neither general wished to risk everything on a concerted attack. However the advantage was with the Franks: they were battle hardened, they had chosen the field, and they had concealed a portion of their force in the wooded uplands, preventing the Muslims from assessing their true strength.

Another problem was that the Muslims could not simply go around the Franks. Tours was a major city and it would need to be conquered and sacked to prevent it raising an army in the Muslims’ rear.

Abd-al-Raḥmân felt compelled to give battle and that his force, comprised largely of cavalry, would win the day. It was he that broke formation, sending out waves of cavalry charges to finally attack the Christian center.

The cavalry charges were witheringly destructive but the disciplined Franks held against the onslaught. Against all military theory of the time, infantry were shown to be able to withstand a cavalry charge, and military tactics were changed forever.

Abd-al-Raḥmân himself was killed towards the end of the day in a Frankish counterattack, shortly before night fell and the battle was paused. When the Franks woke the next day the Muslim camp was deserted.

There would be a second Umayyad invasion a few years later, but it met with defeat. Never again would their armies push from Spain into Europe. It seemed that, with his victory at Tours, Charles Martel had changed the course of history.

Top Image: Charles Martel leads a charge against the Saracens at the Battle of Tours. Source: Levan Ramishvili / Public Domain.

By Bipin Dimri