The scandal of the Cambridge 5 is probably the most prominent and damaging intelligence disaster the United Kingdom has ever had. This group of 5 graduates of Cambridge University, recruited while students and traitors to their country, passed on vital information to the Soviet Union from the end of World War II and into the early stages of the Cold War.

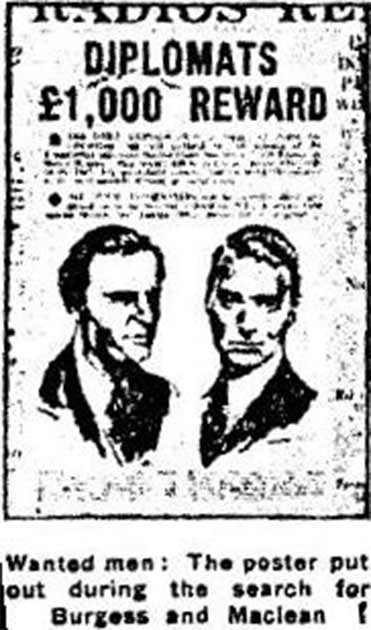

The conspiracy came to the attention of the general public in 1951 owing to the sudden flight of two of the five, Guy Burgess and Donald Maclean. These two members were even honored and given a tribute from the foreign intelligence service of Russia.

As a result of their sudden disappearance, suspicion also fell on Kim Philby, the central member of the five, who himself fled the country in 1963. Apart from these three, the other members of the spy group were called Anthony Blunt and John Cairncross.

All five members of the group were convinced that Soviet Communism’s Marxism-Leninism was the best political system. All of them pursued different careers in the British government in different branches. The gave them access to a a lot of sensitive information, which they passed on to the Soviet Union.

Now that you know a little about the Cambridge 5 let’s get to know about each of the members in detail.

Guy Burgess and Donald Maclean

Before becoming a British diplomat, Donald Maclean pursued his education at the University of Cambridge during the early 1930s. He met Guy Burgess there, who was also to become a British diplomat. The two men were united by an unfavorable opinion of capitalism.

This made them vulnerable to being recruited by Soviet Union intelligence, and so they were. Maclean started providing sensitive information to the Soviet Union in 1934, with Burgess doing so from 1936.

Maclean used to deliver information he obtained from his work as a British Foreign office member, and Guy Burgess did so from his work as a BBC correspondent, MI6 (British foreign intelligence service) member, and later as a British Foreign office member alongside Maclean.

Soon, Burgess and Maclean built up a bad reputation as “hopeless drunks” because they were unable to hide their secret profession when drunk. Once Burgess almost revealed his profession when, while leaving the pub, he unknowingly dropped a secret file that he had taken from the British Foreign Office. Similarly, Maclean also shared with his close friends and brothers that he leaked sensitive information to the Soviet Union.

According to records, Burgess had leaked nearly 389 secret documents containing sensitive information to the KGB in early 1945, and more than 168 documents in the year 1949. Between 1934 to 1951, Maclean was known to have passed a large amount of secret information to Moscow.

However, despite warnings from the US about British secret information being leaked to the Soviets, this all went undetected owing to the fact that the British Secret Service was not ready to take the US warnings seriously.

During early 1951, both Maclean and Burgess both disappeared, making international headlines. Their sudden disappearance made people believe that they were involved in leaking information to the Soviet Union. Their disappearance was linked to a mysterious “third man” who had tipped them off that the authorities were on to them and who was also believed to be a Soviet spy, operating undetected.

The defection of the pair was confirmed when the two of them appeared for a press conference held in Moscow in 1956. By then they were beyond the reach of the West, and the United Kingdom did not even release an arrest warrant for the pair until 1962.

Kim Philby

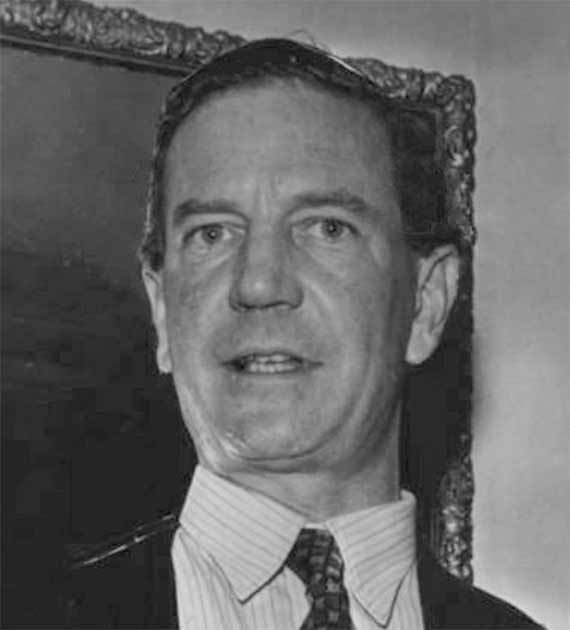

Harold “Kim” Philby, the true “third man” is perhaps the most damaging mole the British Intelligence Service has ever had. He began working as a spy for the Soviet Union in 1934, and provided them with top secret information over the next three decades.

Over that time he rose to become a senior-level officer in the Secret Intelligence Service of Britain, working closely with the CIA chief of counterintelligence, James Jesus Angleton. According to records, Kim Philby was involved in leaking over 900 British secret documents to the KGB.

Investigations about him revealed a number of suspicious matters, suggesting to authorities that he was the “third man” mentioned in relation to Maclean and Burgess. However no strong evidence was found and he was not prosecuted, although he was eventually made to resign from his position in the Secret Service in 1951.

- Who Was Aleister Crowley…Occultist, Satanist, and British Spy?

- Somerton Man: Taman Shud Case Remains Unsolved

In 1955, he addressed the suspicions head on, appearing in a press conference to deny all allegations made against him. In that same year, almost unbelievably, he was removed from the suspect list and became free of all charges.

After his exoneration, Kim Philby went on to work as a journalist in the Middle East. He was offered employment from The Observer newspaper as well as The Economist. He was even re-employed by the Secret Intelligence Service of Britain, to deliver reports from the Middle East region.

A Web Of Defections

In 1961, the Soviet KGB defector Major Anatoliy Golitsyn named several moles within the British and United States intelligence services, including confirming Philby as the “third man”. These allegations led Nicholas Elliott, an intelligence officer stationed near Philby in Beirut, to confront him in 1962.

On 23rd January 1963, Philby vanished from his home in Beirut, appearing in Moscow six months later. His betrayal highly embarrassing for the United Kingdom, who had failed to arrest him when they had the chance.

Furthermore, both the national security of the United Kingdom and the United States was considered compromised by the USSR. Although Philby was gone, he was still a useful advisor to the Soviets, and beyond Western retaliation.

Anthony Blunt

Anthony Blunt was the fourth member of the Cambridge 5. He was the Surveyor of the Pictures of the King (and later Queen), working on the Royal Art Collection. This gave him privileged access to both George VI and Elizabeth II.

He was also at one point a member of MI5 (British domestic intelligence service), using this role to provide the KGB with secret information. He also provided his fellow agents with important warnings of situations that could put them in danger.

In 1964, the MI5 became suspicious of the involvement of Blunt in the leaking of secret information to the USSR. MI5 interrogated Blunt, and he confessed to his crimes in exchange for protection against prosecution.

John Cairncross

John Cairncross, was recruited as a Soviet spy in 1936 by James Klugmann, a prominent British communist. Cairncross was a British literary scholar. He initially worked in the treasury and later in 1940 was transferred to work in the Cabinet Office, at the heart of the UK government.

In the Cabinet Office, he worked as private secretary to Sir Maurice Hankey, Chancellor of the Duchy of Lancaster. After four years in the post, he was moved to MI6.

In the years following World War II, John Cairncross is known to have leaked sensitive information to the Soviets relating to the new NATO alliance. In 1964, during an MI6 meeting, Cairncross confessed to working as a Soviet spy. However, this was kept a secret for a number of years, and like Blunt he was provided with protection against prosecution.

The treachery of Cairncross came to light in 1979 when he made a public confession to Barrie Penrose, a journalist. The news went viral, and people came to the conclusion that John Cairncross was the fifth member of the Cambridge 5.

However, this is not certain. Cairncross himself did not accept that he was a member of the Cambridge 5. He insisted that the information that he had provided to the Soviet Union was not in any way harmful to Britain, and believed that he had maintained his loyalty towards his homeland. A number of researchers believe that Victor Rothschild was the real “fifth man.”

In 1991, Cairncross appeared for an interview with ‘The Mail on Sunday.’ He shared how he leaked vital information to Moscow, and this enabled the Soviets to win the Battle of Kursk against the Germans in 1943.

How Were They Recruited?

Well, you must be curious to know how the Cambridge 5 group was formed and how it all started. According to the National Archives of the UK, the recruitment started in Cambridge University Socialist Society (CUSS).

Kim Philby was elected as the Junior Treasurer of CUSS in March 1932. Here Philby is also known to have met with Maclean and Burgess. In 1934, Philby was recruited by Arnold Deutsch, a shadowy figure working as a Soviet Intelligence Officer in England.

Philby apparently recommended the names of Maclean and Burgess as potential targets for recruitment. While still studying at the University of Cambridge, Maclean, Burgees, Blunt, and Philby had all developed notions and ideas against capitalism and Western democracy, which left them sympathetic towards the USSR and vulnerable to KGB recruitment. It was this led to the formation of the Cambridge 5 spy group.

How Much Damage Did They Actually Cause?

The total damage and negative impact caused by the Cambridge 5 is quite difficult to quantify. However, one thing is sure that Cambridge 5 caused huge embarrassment to Britain and damaged the trust that the United States had in British intelligence. The Cambridge spies were also responsible for providing the Soviets with key advantages at a number of crucial moments.

The leaking of private messages between Winston Churchill and several top Americans by Maclean might have helped Stalin to make ruthless and uncompromised dealings regarding the postwar reorganization of Europe at Yalta. Moreover, the sensitive information passed by Maclean relating to the Anglo-American intentions as well as plans also proved to be helpful for Stalin.

The contributions made by Kim Philby towards Soviet espionage were probably the most damaging of all British traitors on a human scale. He exposed a long list of British agents, leading to several very probably being murdered. Furthermore, his position within the British secret service allowed him to deflect counter-espionage activities, allowing other Soviet spies to escape detection

John Cairncross, on the other hand, may have had the biggest impact on human history. He was responsible for leaking the sensitive details relating to Bletchley Park, the UK codebreaking center in World War II, when he was in the British Foreign Office.

Moreover, his passing on of information regarding the British (and parts of the United States) atomic weapons is known to be the very basis of the nuclear program of the Soviet Union. As Sir Maurice Hankey’s private secretary, he had access to the reports relating to the British atomic program, and passed on this confidential information to the Soviet Union.

The Legacy Of The Cambridge 5

Due to the lack of sufficient evidence or failure to act, the spies of the Cambridge 5 were never arrested and always escaped prosecution. There is even the suggestion that the authorities tried to cover up the cases against the spies and protect their deeds from being revealed in front of the general public. None of the five spies were ultimately punished, and all died a natural death.

Cairncross was never charged with espionage, dying in 1955 in England after suffering from a stroke. Donald Maclean died at the age of 69 from cancer. He was cremated in Moscow with the Soviets calling him a “faithful son and citizen” of the state.

Burgess continued to stay in Russia and drank himself to death, dying when he was 52 years old due to acute liver failure. Antony Blunt lived in seclusion in London and died at the age of 75 from a heart attack.

Finally, Kim Philby, known as the most notorious spy among the Cambridge 5, died in 1988 when he was 76 years old. He had spent his last 25 years of life in Moscow. According to his wife, he felt tortured owing to his betrayals and his failings. He also started drinking a lot, and eventually this led to his death.

Makes For a Great Story

The story of the Cambridge 5 has been a fruitful one for writers. John le Carre, the Cold War novelist, based his famous novel Tinker Tailor Soldier Spy on the story of the Cambridge Five. Alan Bennett, the English playwright, wrote An Englishman Abroad, a dramatization of Guy Burgess in Russia.

Traitor, a television play by Dennis Potter, revolves around a central character named Adrian Harris who is interviewed by western newspaper reporters in order to gain insights into his defection. Harris seems to be a mixed character of Burgess, Philby, and Maclean. Cambridge Spies is also another popular television drama that sheds light on the doings of the spies to the Soviet Union.

This is just the tip of the iceberg, and there have been many films that draw inspiration from the story. Another Country, The Imitation Game, The Jigsaw Man, and A Different Loyalty all owe their inspiration to the espionage activities of the Cambridge 5.

But while all these works of fiction show how enduringly fascinating the story is, none of them are able to answer the question at the heart of the matter. Sympathy to a cause is one thing, but we will never truly know why such clever men in privileged positions chose to betray their nation so utterly.

Top Image: None of the Cambridge 5 were ever prosecuted by the United Kingdom. Source: jgolby / Adobe Stock.

By Bipin Dimri