Here’s a question we bet you never thought you would hear: in 1943, during the height of WW2 were 1,400 African American soldiers from the 364th Infantry Regiment executed at Camp Van Dorn?

It seems a crazy proposition. The deaths of so many men would be notable at any point in history. Add to this the fact that they occurred on American soil, and that the executions were ordered by the US Army, and the story becomes even more unbelievable.

And yet the rumor stubbornly refuses to go away. Multiple investigations have been launched over the years seeking the truth, but some questions remain unanswered.

How much of this story is the truth?

The 364th Regiment and the Thanksgiving Riot of 1941

The United States Army of World War II was, in many ways, a far cry from what it is now. For a start, it was still segregated and divisions between white and black troops ran deep. The 364th Negro Infantry, formed in 1941, was one of many all-black regiments in the army.

Founded at Camp Claiborne, Louisiana, the regiment was mainly made up of soldiers from northern states, mostly Chicago, Philadelphia, and New York. The regiment was made up of black soldiers but ruled over by white officers.

As was common at this time, these white officers had a reputation for mistreating the black soldiers under them. When the soldiers tried writing letters to their congressmen and senators to complain, their commanders intercepted the complaints and used them against them.

By the time the 364th was sent to Camp Florence, near Phoenix in Arizona, in late 1941 it already had a reputation for being “troublemakers”. They had been sent to Camp Florence to guard over the German prisoners of war currently being held there. As postings go during wartime this should have been a rather comfortable one.

However, it didn’t take long for trouble to start brewing. Thanks to the Jim Crow laws of the period the South was still deeply segregated.

Phoenix’s population was around 7% black and other minorities like Hispanics and Native Americans had restricted daily lives and rights. This was something that did not sit right with the 364th’s soldiers who were used to a slightly less institutionalized form of segregation back home in the North and were already bristling at the abuse they received from their officers.

That Thanksgiving Day roughly 100 members of the unit were involved in Phoenix’s Thanksgiving Day Riot. Many of the soldiers visited the bars of the city’s black neighborhood and trouble broke out after black MPs from Camp Florence turned up and began arresting their fellow soldiers. As shots began to ring out, members of the 364th responded by grabbing their rifles and returning to the area.

The unrest began to spread and local law enforcement and soldiers from the camp had to be brought in to try and calm things down. A 28-block square area was blockaded to try and capture the soldiers.

A total of three people were reportedly killed: a white officer, an enlisted man and a civilian. 12 other enlisted men were injured. Troublingly, it has long been suggested that many more civilians were killed during the riot, but since it took place in a black area of the city, casualties were under reported.

The Camp Van Dorn Massacre

As punishment for their perceived transgressions while stationed in Arizona, the 364th was sent to Camp Van Dorn near Centerville, Mississippi on May 26, 1943. The unit continued to fight for equal treatment and throughout their time there it was normal for 65-85 men to be in the stockade for minor infractions at any one time.

For example, one young man, Francis Johnson of Chester, was locked up and limited to bread and water for over two weeks. His crime? Protesting after being kicked by his white officer.

Just a few days after they arrived at Camp Van Dorn one of the unit’s men, Private William Waker, got into a scuffle with MPs outside the base’s entrance. He was returning from rest and recuperation when white MPs stopped him at the gate and tried to arrest him because his uniform was missing a button. Seeing this as unfair treatment, Walker resisted.

The local sheriff saw the altercation and stepped in by shooting Private Walker. When his fellow soldiers heard what had happened, they broke into the armory and took rifles and ammunition, preparing for revenge.

According to reports a black MP riot squad was called out and fired shots into the crowd, hitting one soldier in the leg. If one believes the official record, this was the sum total of the “Camp Van Dorn Massacre.”

However, according to loan officer Carroll Case, 1,200 members of 364th Regiment were lined up by white soldiers and civilians and shot that day. He recorded his version of events in his 1998 novel, The Slaughter: An American Atrocity.

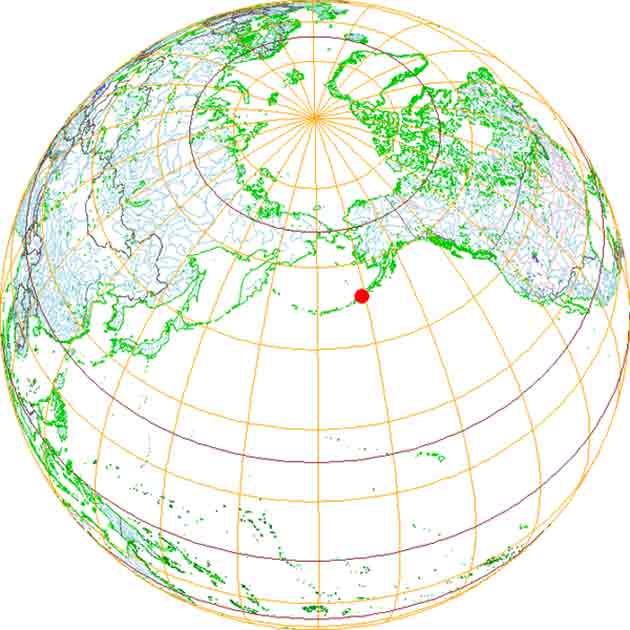

As part of an alleged cover-up, most of the remaining regiment was then sent to the Aleutian Islands in Alaska where they repulsed several Japanese Army attacks at Amchitka Island. Some 300 other members are believed to have been transferred to other units. By 1945 the regiment had been completely disbanded.

Massacre or Hoax?

If true, the massacre would be one of the worst racial atrocities in US history. Which is saying something.

The problem is there’s next to no evidence that the massacre even took place and Carrol’s book is almost a complete work of fiction. The US Army for its part has consistently denied the massacre.

- Knights of the Golden Circle: A Pro-Slavery Empire

- Unchecked Aggressions: The Lynching of Robert Prager

It is in Carroll’s book that we find the answer. It is made up of two parts, the first of which claims to be historical fact and features limited historical documentation to back up its claims.

The second part is a fictional account of the events Carroll claims happened that day. Most of his ideas are based on the accounts of two residents who claimed to have witnessed the massacre as well as a soldier. However records show this soldier wasn’t stationed at the camp during the massacre and died long before Carroll released his book.

What he doesn’t have is the accounts of any members of the 364th or any of the 30,000-odd other soldiers stationed at the camp that day. Not a single whistle-blower or person with a guilty conscience has ever come forward. That makes Carrol’s claims feel a bit unlikely.

Furthermore, after Carroll’s claims began receiving national attention the National Minority Military Museum Foundation decided to investigate. It quickly found that the writer’s claims had no historical documentation and deemed his book a hoax.

These findings were later backed up by a more than year-long investigation which was carried out by the Department of Defense in 1999. The assistant secretary of defense dubbed Carrol’s claims a: “work of fiction and a marketing grab”.

The military’s subsequent report pointed out that “All of the nearly 4,000 men who were assigned to the 364th in 1943 have been traced to their separation from military service.” It may make for a lurid tale, but it has been entirely debunked.

This isn’t to say that nothing bad ever happened to the 364th Regiment. Rather suspiciously between June 1943 and 1945 (when it was disbanded) over 800 names disappeared from its regimental roster. That’s quite a few soldiers to lose, suggesting something was going on.

Furthermore, the above investigations may have found no evidence of a massacre, but their findings were still deeply disturbing. They found plenty of evidence of cruel and unusual punishments being heaped upon the regiment and plenty of racist and unfair treatment being carried out by its white officers. Whenever things heated up the army simply shipped the regiment off to a new posting where the cruel treatment could start fresh.

Sadly, Carroll’s outlandish claims overshadowed a very real conspiracy. For far too long minority soldiers suffered while serving in the armed forces, their voices all too often silenced. Only by shining a light on these atrocities can society begin to heal.

Top Image: We 1,200 US servicemen shot at Camp Van Dorn? Not everything is as it seems. Source: Zef Art / Adobe Stock.