When, in 1973, permission was granted for King Casimir IV Jagiellon’s burial coffin to be exhumed, Polish archaeologists were ecstatic. Such permission is given only in extremely rare cases, and they would be offered a privileged opportunity to inspect the tomb of a dead king.

However, little could have prepared them for what was to come. And when their fortune swiftly turned fatal, many feared that the lethal “King Tut curse” had struck yet again.

Casimir IV Jagiellon: The Duke of Lithuania

Casimir IV Jagiellon, the son of Polish King Wadysaw II Jagiello, was born on November 20, 1427. An elderly father, Władysław was 75 when Casimir was born. As he was only second in line to the throne Casimir didn’t receive a formal education, did not take classes in Latin, and was not given much instruction regarding the responsibilities of the office of the crown.

At the young age of thirteen, Casimir was proclaimed the Grand Duke of Lithuania. During his tenure of reign as the duke, it is said that he treated everyone equally, regardless of race or religion. However after only three years as duke, his father King Wadysaw II passed suddenly due to an untreatable cold that had taken hold of him.

Poland was suddenly trusted into the hands of Casimir’s older brother Władysław III, but not for long. In 1444, only one year after his father’s death the new King Władysław III was slain at the Battle of Varna. In 1449, Casimir, the Duke of Lithuania, was crowned King of Poland.

It was an inauspicious start, but in the long years until his death the king would come to be seen as one of the most successful rulers of Poland. In 1466 he succeeded in overcoming the grand power in the region, the Teutonic Order, after waging a tax and meeting them head on in what is known as the Thirteen Year War. Furthermore, he reclaimed one of Poland’s most important cities off the coast of the Baltic Sea, the city of Pomerania.

- The Legendary Curse of King Tutankhamun’s Tomb

- Where was the First Rzeczpospolita? Europe’s Huge Hidden Country

With a strong and trusted parliament and advisors around him, the young monarch managed to elevate Poland’s economic standing by aligning Prussia with the Polish state. Casimir became one of the most progressive Polish kings and established one of the most prestigious and powerful dynasties in all of Europe thanks to his determined and successful political efforts.

A Dead King and Decaying Body

But, it could not last forever. On a hot, sunny day in June 1492 King Casimir IV died at the age of 64 from causes unknown. However, there was one oddity: it was noticed almost immediately after his death that the late king’s remains were decomposing far more quickly than was typical for a freshly deceased body.

The body was covered with calcium salt, draped in expensive silks, and placed in a coffin made of wood that had been sealed with resin to preserve it for the journey to Wawel Cathedral, where it would be laid to rest forever. Poland’s great ruler was laid to rest on July 11, 1492, but for how long?

Not for ever, it would seem. The royal relics and tombs passed through the hands of the various authorities until it fell to Poland’s communist government of the 1970s, who imposed highly stringent regulations. Even requests by eminent academics and researchers to exhume King Casimir IV’s remains for research and conservation were turned down.

The casket wasn’t dug up until Cardinal Karol Wojtyla, the obstinate archbishop of Krakow who would later become Pope John Paul II, demanded the exhumation. The only worry that remained was the possibility that the tomb would be found to have been abandoned after being looted during World War One. Russians were known to target royal burial tombs.

When Polish media got wind that their beloved King Casimir IV was to be dug up the story caught the attention of the nation. Before the burial site was exhumed the archaeologists and citizens alike joked that the tomb was cursed and those who continue should proceed with caution.

Such stories are common amongst ancient tomb explorers. Sadly, this joke ended with some not-so-laughable outcomes.

A Biological Time Bomb

Researchers opened the almost 500-year-old coffin on April 13th, 1973, to find the wooden coffin had rotten away and what remained were sections of the king’s decaying corpse. At first glance, their discoveries were consistent with what was anticipated to be discovered in a medieval burial tomb.

- Mausoleum of Augustus: Why Are There No Tombs of Early Roman Emperors?

- The Curse of Tippecanoe: Are some US Presidents Fated to Die in Office?

But the curse was quick to strike. Four researchers who had been working in Wawel Cathedral on the exhumation of the tomb passed away from infections in the following few days. Suddenly this seemed to be a repeat of a similar event that happened fifty years previously.

In 1922 the famous burial chamber of the ancient Egyptian ruler King Tutankhamun was uncovered. With this exhilarating find came the sudden death of nine archaeologists involved in the tomb’s unearthing.

Additionally, over time, up to fifteen researchers who were either working on-site at the tomb of King Casimir IV or handling the artifacts in labs began to experience health problems and eventually passed away. It appeared that anyone exposed to the discovery found themselves on death’s door. By disturbing those who had been laid to rest, had they tempted faith?

The Curse of Aspergillus Flavus

In fact, in 1999 a German microbiologist examined the remains of multiple mummified corpses which had been exhumed from around the world. What he found was numerous types of mold spores that cause potential health risks to humans if inhaled.

Most of them contained a saprophytic and pathogenic fungus called Aspergillus Flavus. These fungi infect animals and cause allergies, asthma, and other respiratory problems in healthy individuals, but if they were to enter the body of an immunocompromised person, they most likely be fatal.

To avoid contracting the venerable ancient curse, archaeologists today who study ancient ruins or tombs must be in good health, have not recently received cancer treatment, and have no pulmonary or cardiovascular conditions.

Like the archeologists and scientists who entered the tomb of King Tutankhamun, the researchers had unknowingly exposed themselves to a deathly infectious fungus. Prying into the tombs and the past meant they had signed their death certificate. In this unfortunate case curiously did kill someone.

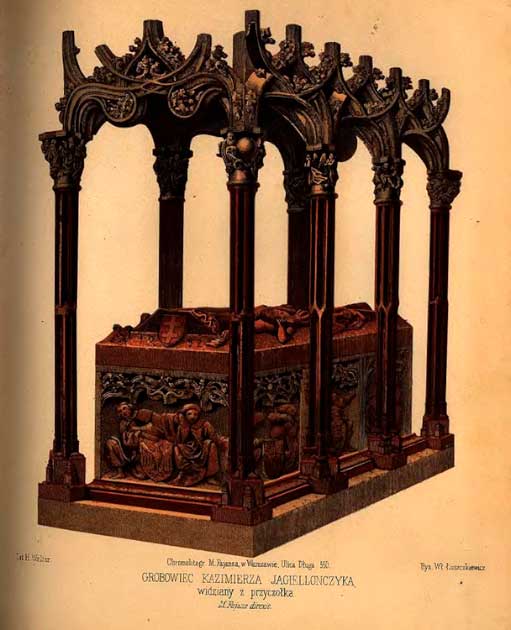

Top Image: Tomb effigy of Casimir IV from Wawel Cathedral. When his tomb was opened in 1973 many believed it was cursed. Source: Maksymilian Fajans / Public Domain.

By Roisin Everard