Hidden from history for over a century, Scotland Yard took seriously the possibility that an American man was the notorious Jack the Ripper. The suspect’s name was Dr. Francis Tumblety. He was a quack doctor and fake Indian herbalist, who was in London at the time of the murders. Police arrested him, and after posting bail, he sneaked out of the country and sailed back to New York City. Meanwhile, Jack the Ripper’s murders stopped.

Since they had nothing on Tumblety for the murders upon his arrest, Scotland Yard soon charged him with a convictable misdemeanor offense to hold him. This was not an extraditable charge in the United States. Thus, Tumblety had no legal requirement to go back to England. Six months later in July 1889, someone killed another prostitute. At the time, Scotland Yard believed she was also the victim of Jack the Ripper. Since Tumblety was in New York, police took him off the suspect list. Experts agreed only later that Jack had not committed the 1889 murder.

An Interesting Letter

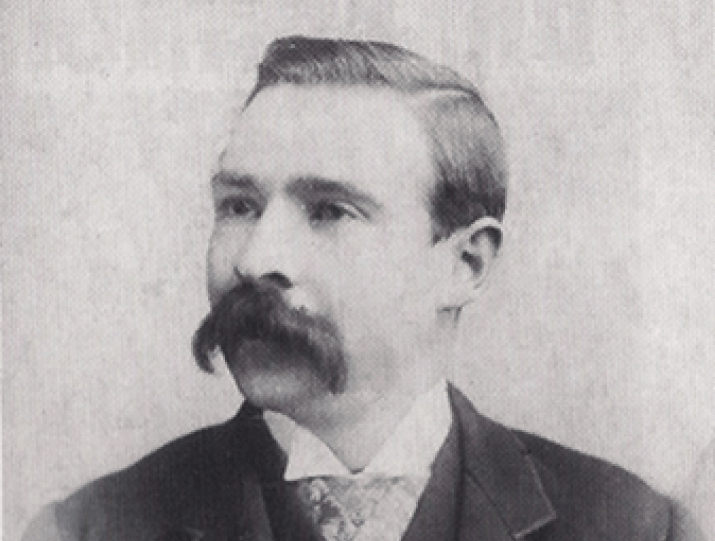

In 1993, retired Suffolk Constabulary police officer and crime historian Stewart P. Evans uncovered a private letter dated September 23, 1913. Chief Inspector John Littlechild, head of the Metropolitan Police Special Branch, had written it and addressed it to famous journalist George R. Sims. In it, Littlechild revealed that Dr. Francis Tumblety became an important suspect after the Mary Kelly murder. He stated to Sims that “amongst the suspects,” Dr. Francis Tumblety was “a likely one.”

Stewart Evans then discovered that Tumblety’s arrest on suspicion had been in the newspapers at the time, especially in the U.S. dailies. Newspaper reports claimed that Tumblety was initially arrested on suspicion of the Whitechapel crimes. However, when the police had insufficient evidence to hold him, they re-arrested him on a misdemeanor charge of gross indecency and indecent assault. Apparently, Dr. Francis Tumblety engaged in sexual relationships with young men. In the nineteenth-century in England, this was an illegal act. During his arrest, Tumblety had a correspondence in his possession, which allowed Scotland Yard to pursue the gross indecency and indecent assault case against him.

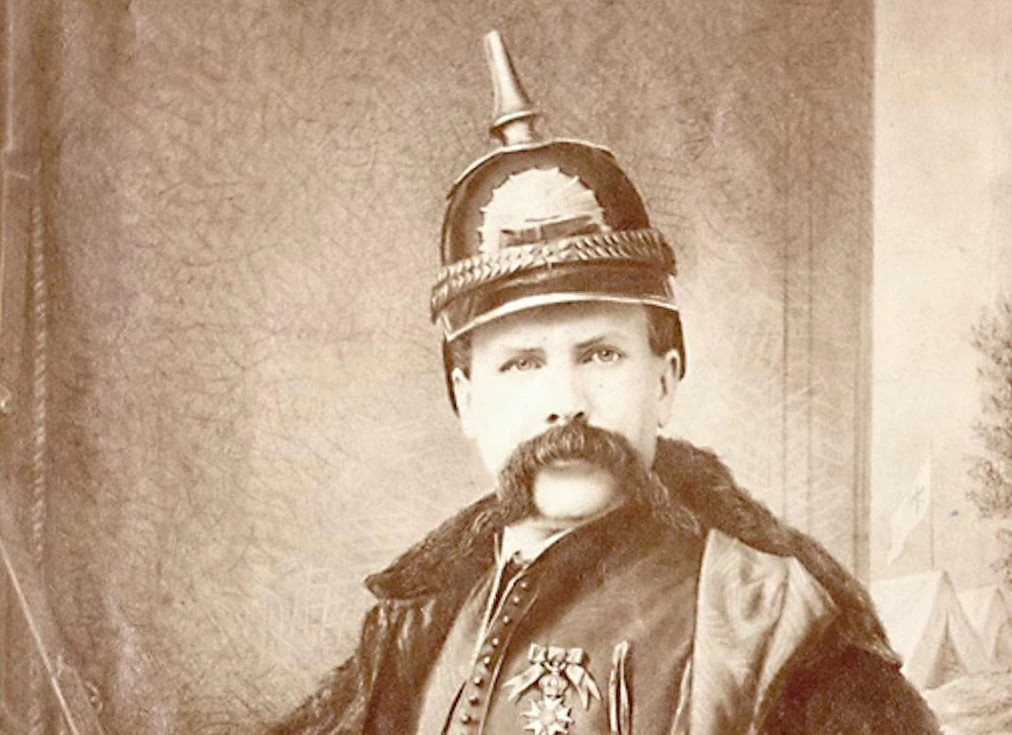

The Controversial Dr. Francis Tumblety

Dr. Francis Tumblety was a relatively well-known and somewhat notorious figure in the mid-nineteenth-century in North America. He was born in Ireland around 1833, and in 1847, he immigrated with his family to Rochester, New York, on the coffin ship Ashburton during the Irish potato famine. As a teenager, he was employed as a steward by a Rochester doctor who proclaimed himself an expert on “‘French cures for sexual diseases.” Tumblety peddled the doctor’s sexually-explicit literature on the Erie Canal boats. Soon after, a man named Rudolf Lyons set up a temporary office in town. He called himself “The well-known and celebrated Indian herb doctor,” which immediately attracted the attention of young Tumblety. When Lyons left, Tumblety followed, and he quickly learned the trade.

By 1855, Francis Tumblety started on his own in Detroit, Michigan, as a full-fledged Indian herb doctor. However, he also continued the practice of selling French cures literature for sexual diseases. Although it was untrue, he also claimed to have received a medical diploma through a medical school. The charlatan began signing his name with M.D. Thus began his highly successful traveling quackery. Subsequently, he left Detroit and traveled through Canada from Toronto to St. Johns and eventually made his way to New York City by 1860.

Tumblety’s Notoriety Grows

Tumblety’s chosen profession ensured that his name was always in the daily newspapers everywhere he traveled. In any public setting where many eyes were upon him, Tumblety displayed his flamboyant Liberace-type character. Although nearly all accounts describe him as peculiar, the fact that people regularly called upon him suggests that his schemes were successful. Indeed, he was earning hundreds of thousands of dollars.

You May Also Like: Was America’s H.H. Holmes Jack the Ripper?

For example, as he came to a new city in the United States and Canada, he would enter as though he was entering a circus ring wearing a flashy outfit and riding a beautiful horse. A valet and two huge dogs followed closely behind him. However, legal problems also followed him closely because he practiced without a license and used the M.D. designation in his signature. In 1860, while he was in St. John, a patient died in his care. Authorities charged him with manslaughter. Instead of facing the music, Tumblety left Canada under cover of darkness and eventually settled in New York City.

After the defeat of the Union forces at the first major battle of the American Civil War just outside of Washington D.C. on July 21, 1861, President Lincoln appointed Major General George B. McClellan as Commander of the Army of the Potomac. McClellan was responsible for the defense of the capital. At this time, Francis Tumblety began his “two-year sojourn” at Washington D.C. He stated in his autobiography that he partially made up his mind to tender his “services as a surgeon in one of the regiments.”

Herb Doc or Surgeon?

Contemporary newspaper reporters repeated his boast of being on McClellan’s surgical staff. Once he arrived, papers reported he was promenading up and down Pennsylvania Avenue. Interestingly, he did not flood the papers with his usual newspaper advertising campaign as a famous Indian herb doctor before his arrival. Instead, he waited for six months and began his campaign in 1862. This change in business practice makes sense, since he was attempting to convince the General that he was a surgeon, not an Indian herb doctor.

The problem for Tumblety was that he did not have a medical diploma and was not a real surgeon. Unsurprisingly, he did the next best thing. He invited the General’s officers to an illustrated medical lecture. This was a practice that prominent surgeons performed in the nineteenth century to demonstrate their credibility.

The Collection of Uteruses

At the conference, he revealed his anatomical collection, specifically, his prized collection of uterus specimens. Perhaps these included the same uteruses that were taken by Jack the Ripper from two of his victims. The man who saw Tumblety’s uterus collection was New York City lawyer and Civil War reptile journalist/spy Charles A. Dunham. Dunham stated to a New York World reporter on December 1, 1888, that he was a colonel when he met Tumblety in the capital. His position as one of the General’s officers would have been why Tumblety invited him to the lecture. The General’s officers were his eyes and ears. Once the General rejected him by the end of 1861, Tumblety left for two months. However, he returned and decided to practice his money-making scheme as an Indian herb doctor. In February 1862, he began advertising himself.

Did Dunham lie to the reporter about Tumblety having an anatomical collection and giving the medical lecture? Interestingly, just before Tumblety arrived in D.C., people saw him in New York City with pictures of anatomical specimens posted outside his Broadway Street office, “which look as if they might once have formed part of the collection of a lunatic” (Vanity Fair, August 31, 1861). Further, Tumblety made his way to Buffalo, New York, after his two-year sojourn at the capital. The Buffalo Courier reported that Tumblety gave medical lectures, “with Thespian emphasis.”

Move to London

In the 1880s, the world traveler was spending half the year in England. In May of 1888 – the year of the Ripper murders – Tumblety sailed across the Atlantic and made residence in West End London. During the murders, police arrested him on suspicion for the Whitechapel crimes. This occurred sometime before police took him into custody on November 7, 1888, for gross indecency and indecent assault. They immediately brought him up in front of Marlborough Police Court Magistrate James L. Hannay for his remand hearing. This would determine if he should remain in custody at Holloway Prison until his committal hearing one week later. Hannay had the discretionary powers to give Tumblety bail. On November 9, 1888, just one or two days later, Mary Kelly suffered a brutal death.

Tumblety had his committal hearing on November 14, 1888. Magistrate Hannay listened to the evidence and agreed the case should be brought up to the judge at Central Criminal Court on November 20, 1888, following a grand jury review. Hannay set bail at £300, and on November 16, 1888, Tumblety posted bail. Holloway Prison released him, and he was free.

Did Hannay set bail at the earlier remand hearing, allowing Tumblety to be free at the time of the Kelly murder? If the magistrate set bail at the later committal hearing for the same offense, he likely did the same at the earlier remand hearing, especially since the case against Tumblety was in preparations for the committal hearing. The fact that three Scotland Yard officials considered Tumblety a suspect after the Kelly murder supports this.

Fleeing England

After posting bail, Tumblety slipped into the English shadows. On November 20, Tumblety instructed his lawyer to request a postponement. The courts approved the request and scheduled it for December 10, 1888. Interestingly, Tumblety’s New York bank transferred approximately £260 transferred on November 20. He sneaked out of England to Boulogne, France, on November 23, 1888. He embarked on the transatlantic steamship La Bretagne at noon in Havre, France, on November 24, and arrived in New York City on December 2, 1888. Because the charge was a misdemeanor offense, Tumblety would not face extradition back to England.

On Amazon: Michael L. Hawley’s book – The Ripper’s Haunts

Six months later, on July 17, 1889, someone murdered Alice Mackenzie. Scotland Yard believed she was the Whitechapel fiend’s victim. Since Tumblety was in New York City, this convinced police that Tumblety was not Jack the Ripper. The world soon forgot about him. Only later did people realized that Jack did not murder Mackenzie.

Tumblety had two personas. Publicly, he was a ubiquitous, eccentric, aristocratic medical professional. However, privately, he was a narcissistic loner, frequenting the slums of every city seeking encounters with young men. On countless occasions, Tumblety found himself in legal trouble, defending against various charges including assault.

The Main Reason Tumblety Became a Suspect

The primary reason journalists reported Tumblety as a suspect was the idea that the Whitechapel murderer hated women. This is precisely what Littlechild stated in his private letter, “…his feelings toward women were remarkable and bitter in the extreme, a fact on record.” Littlechild’s recollections were surprisingly detailed and accurate about Tumblety being a suspect after the Kelly murder. He also alluded to Tumbelty’s bitter hatred of women. Additionally, his arrests and escape from France made him very suspicious.

Scotland Yard’s identification of Tumblety in France could only have come from officials in Litttlechild’s Special Branch division, which explains why he knew of Tumblety’s escape. However, law enforcement then makes a blatant error. “He [Tumblety] shortly left Boulogne and was never heard of afterward. It was believed he committed suicide…” Tumblety made it safely back to New York and died in 1903. The incredible accuracy of Littlechild’s earlier comments suggests this error did not stem from a lapse of memory. More likely, Littlechild did not participate in the case after authorities identified Tumblety in France.

Another reason officials suspected Tumblety was because he preferred young males for sexual companionship. Theories flew that he had an unusual hatred of women, or misogyny, which had begun in his teenage years in Rochester, New York. Supposedly Tumblety stated that women were a curse to the land, and he even blamed them for all the world’s trouble. He considered them imposters who lured young male youths away from their intended lovers: older men.

Breaking News

The journalist who broke the story of Tumblety’s arrest on suspicion of the Whitechapel crimes was the New York World’s London Special correspondent, E. Tracy Greaves. The story surfaced in his Saturday, November 17, 1888, news dispatch. The report was a weekly update on the Whitechapel murders investigation one week after the murder of the last victim, Mary Kelly, on November 9.

American reporters also used the police as their source for the Whitechapel investigation. Greaves even admitted to having a Scotland Yard informant.

In an interview with a New York World reporter in January 1889, Tumblety admitted to his arrest in England. He said:

[blockquote align= “none” author= “Francis Tumblety”]I happened to be there when these Whitechapel murders attracted the attention of the whole world, and, in the company with thousands of other people, I went down to the Whitechapel district. I was not dressed in a way to attract attention, I thought, though it afterward turned out that I did. I was interested by the excitement and the crowds and the queer scenes and sights, and did not know that all the time I was being followed by English detectives.[/blockquote]

Other Details

Two Scotland Yard officials mentioned Tumblety as a suspect after they completed the case for indecency and indecent assault. Assistant Commissioner Robert Anderson sent private cable dispatches to at least two U.S. chiefs of police. He asked San Francisco’s Patrick Crowley and Brooklyn’s Patrick Campbell for all the information they had on Tumblety.

A misconception is that Anderson requested handwriting samples, but this did not occur. He merely asked for all information. Nonetheless, Crowley did offer handwriting samples, and Anderson accepted them. He sent these cable dispatches on November 22, before they realized Tumblety had sneaked out of the country.

Also, when Inspector First Class CID Walter Andrews was in Toronto, Canada, on December 11, 1888, a reporter asked if he knew Tumblety in reference to the murder case. Andrews stated:

[blockquote align= “none” author= “Inspector First Class CID Walter Andrews”]Do I know Dr. Tumblety, of course, I do. But he is not the Whitechapel murderer. All the same, we would like to interview him, for the last time we had him he jumped his bail. He is a bad lot.[/blockquote]

If Andrews stated Tumblety was not the murderer, why did he still want to interview Tublety? Getting an interview for the gross indecency case would have been fruitless since he could not be deported. Perhaps it’s because he believed Tumblety might face murder charges if more evidence turned up.

On December 4, 1888, journalists reported on an English detective staking out Tumblety’s residence. Purportedly, the detective told a bartender that he was investigating the chap who committed the Whitechapel murders.

Could Francis Tumblety Be Jack the Ripper?

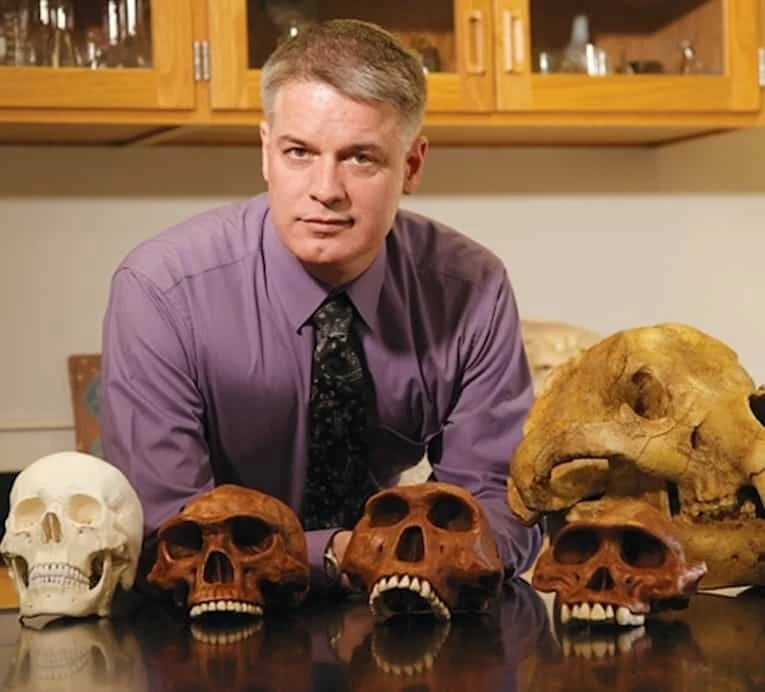

If the Whitechapel murders were sex crimes, then Francis Tumblety was not Jack the Ripper. Most gay male sado-sexual serial killers prey upon men, as with Jeffrey Dahmer. However, in Tumblety’s case, the evidence shows that his motive would have been a hatred of women.

Some modern experts do not see the Whitechapel murders as sexually-motivated or even sadistic. Forensic pathologist Dr. William Eckert M.D. investigated the Whitechapel case in 1989. He concluded that the motive was anger-retaliation exhibiting non-sadistic behavior. Forensic scientist and criminal profiler Dr. Brent Turvey also observed the victims of the Whitechapel murders. He did not see a sexual motive, but anger-retaliation: specifically, misogyny.

Interestingly, in January 1888, the year of the murders, Dr. Francis Tumblety told a Toronto mail reporter that he was in constant dread of sudden death for kidney and heart disease. How coincidental that the three organs removed from the Whitechapel victims included the uterus, kidney, and heart.