“And yet it moves.” It is among the most famous phrases said by the famous Italian scientist Galileo Galilei. This phrase, supposedly muttered as he left the room where he was undergoing interrogation by the Catholic Inquisition, tells us much about the Catholic Church, and the man whom they were questioning.

Galileo’s astronomical observations had led to an entirely new understanding of the heavens and the movement of the planets. But, in challenging the accepted religious dogma that the Earth was at the center of the universe, it also created conflict with the Church.

A Scientific Observation

Galileo was very much convinced that the notion of the Earth being static was false, and he wanted to prove the same. As a result of his astronomical experiments and observations, he had concluded that Earth is not standing still, but instead revolves around the sun, much like all of the other planets in the solar system.

This was a dangerous statement to make, as it offered scientific evidence that the Church, and through them the supposed word of God, was wrong. The Church could not let such a statement stand, and Galileo was put on trial under suspicion of heresy.

Under trial and in fear of his life, Galileo was forced to recant and confirm the Church’s position that the sun and all the planets revolve around the Earth. But he was certain of his own conclusions and knew what he had seen. And so, he uttered the immortal phrase:

“Eppur si muove”

But did he?

In the years and decades after the incident, various versions of the story emerged. Some claimed Galileo angrily responded to the Inquisitor with this phrase, challenging Church doctrine openly. Many think this was too good to be true, and question whether he said the words at all.

Mario Livio, an astrophysicist and author of a biography named Galileo and the Science Deniers. Is uncertain of whether the phrase was truly uttered. While researching his book, he found it difficult to unveil whether Galileo actually said those words.

Looking back to the earliest evidence, he turned to the first biography of Galileo. This was authored by Vincenzo Viviana, his protégé, from the year 1655 to 1656, and had no mention of this phrase.

- 10 Interesting Facts About Jupiter

- Outrageous Astronomy – Who Was Behind The Great Moon Hoax of 1835?

As per Livio, the first mention of this phrase in text was in the form of a single paragraph, within the print in the year 1757 named the Italian Library, authored by Giuseppe Baretti. It was written around 100 years after the death of Galileo.

In conducting his research Livio had reviewed the work of Antonia Favaro, a historian of science and expert on the life and work of Galileo. In the year 1911, Favaro published several articles summarizing his collective efforts in order to determine the origin of this famous phrase, “And yet it moves.”

Livio decided to follow-up on Favaro’s work, a century later. Favaro had received a letter from a man named Jules Van Belle of Belgium, who owned a painting depicting the Earth revolving around the sun, dated from circa 1643.

This painting would have been completed just one year after the death of Galileo that the painting was made. At the bottom of the painting appears the famous motto.

Painting the Truth?

The painting was made by a Spanish painter named Bartolome Esteban Murillo. Van Belle believed that this painting once belonged to Commander Ottavio Piccolomini, the brother of the Archbishop of Siena.

Galileo had served the first 6 months of his tenure of house arrest at the residence of Siena’s Archbishop. This puts him very close to the painting, both physically and in time.

This would seem strong evidence that Galileo said those famous words, but this does not confirm that he said them in front of the Inquisitor. Sadly, this painting has never been examined by historians, and the authenticity of the phrase has never been verified.

Livio had not been able to locate the original of this supposed painting of Murillo, but instead consulted with art experts who specialized in decoding Murillo’s art. When they viewed photographs of the painting, the experts were clear: it was not the work of the Spanish painter.

After hunting for years, Livio finally re-discovered the painting in a private collection. The painting had been purchased 2007 from one of the descendants of Van Belle.

A Much Later Date

The auction house dated the painting to the 19th century, which would make it much later than Van Belle had claimed. This would mean the painting would be useless as evidence that Galileo said this phrase. Permission is still pending for Livio to get the painting examined by the art historians.

The auctioneers listed the painting as a painting by the Flemish painter Henrij Gregoir in 1837, the same year when Van Maldeghem completed Galileo’s portrait with the same title. but, until the painting can be assessed by historians, the date remains uncertain.

After completing his research for the book, Livio said that even if Galileo didn’t say these words, it was definitely reflective of what he believed. These were observable facts and were under attack by the Church, who preferred the preserve their authority rather than welcome a new understanding of the world.

So, did the great man say these words and in doing so defy his faith, embracing the observable facts of the universe even when they went against the word of God? Even if he did not, he was certainly prepared to report what he saw,, even when it defied religious orthodoxy.

In doing so, we are gifted a snapshot of a man who would follow his science to wherever it led, even if the conclusions could be a threat to himself. His intellectual honesty provided a breakthrough in our understanding, even if he was unable to confirm it in anything further than a muttered aside.

Conclusion

Galileo’s observations overthrew the standard model of the universe which dated back to Aristotle, some 1,500 years earlier, confirming the theories of Copernicus a century before. His new understanding, since proven to be correct and accepted almost without objection, paved the way for advances in astronomy, and broadened the horizons of humanity.

So, did he say it? In the end it doesn’t matter. He saw it, and in his observations we came to see the universe in a whole new way. Against the truth, even religious doctrine must eventually crumble.

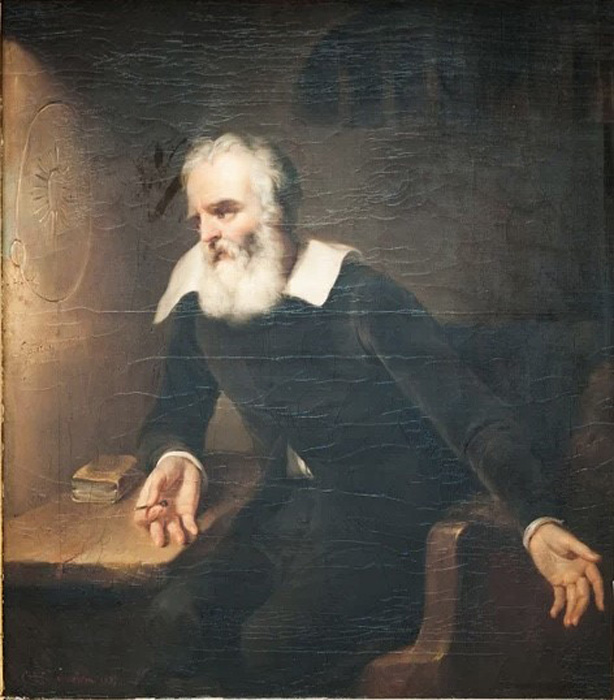

Top Image: Galileo defends himself in front of the Holy Inquisition. Source: Joseph-Nicolas Robert-Fleury / Public Domain.

By Bipin Dimri