Warfare is a powerful crucible for innovation. Technologies which take decades to understand in peacetime are subject to rapid development during times of crisis, driven by the need to survive and conquer.

Some ideas seemingly come from nowhere, wanting only the spark of inspiration. Others are brilliant in conception but are beyond modern technology, limited in execution by what is available at the time. In fact, many “modern” approaches to warfare have their roots in such an earlier time, where the ideas were there but the know-how was not.

In the modern day, more than a dozen nations have developed unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs), or pilotless aircraft. Such vehicles, either as weapons-delivery systems or weapons in their own right, have come to be a defining aspect of modern combat.

But the idea is nothing new. The first attempts to create a pilotless plane date back much further, to the early years of the First World War.

A Question of Pilot Mortality

In 1915, war was raging across Europe, in the trenches, at sea, and for the first time in the air. Life piloting a biplane above the fields of battle may seem glamorous but it was also extremely dangerous, and many pilots lost their lives at the controls of the flimsy wooden and fabric contraptions.

The United States, eyeing their possible involvement, could clearly manufacture the planes but lacked the pilots to put in them. Clearly what was needed was a different use for the planes, one which degraded the enemy without sacrificing the pilot.

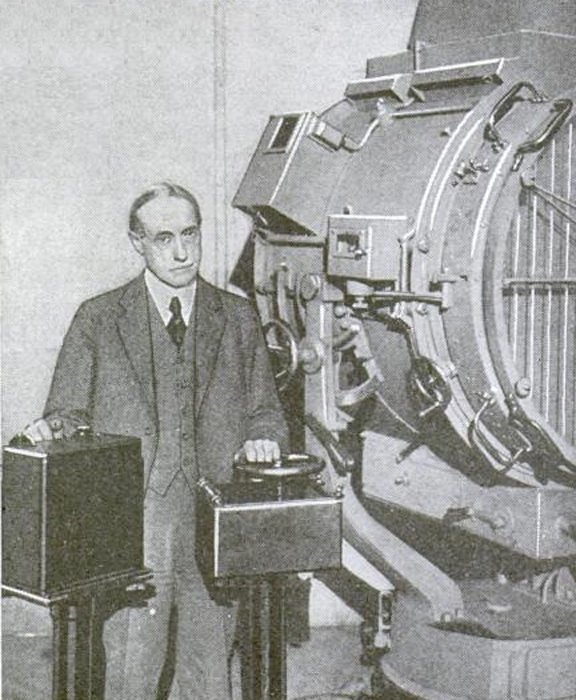

Based on this, the US Secretary of the Navy Josephus Daniels and inventor Thomas Edison proposed a board of prominent inventors to help prepare the United States for war. This was known as the Naval Consulting Board, and among the board members, were scientist-inventors Peter Cooper Hewitt and Elmer Sperry.

Hewitt was an expert in both aeronautics and radio communication, while Sperry’s genius as a engineer had been used in building gyroscopes for the US Navy. Spurred by the need to innovate, Hewitt began with the development of an “aerial torpedo” and soon involved Sperry in the project.

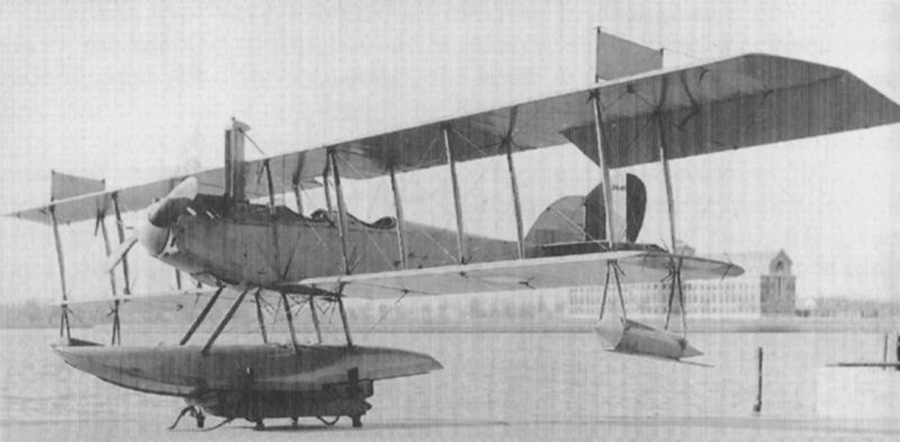

Sperry had already demonstrated an automatic gyrostabilizer, a spin off of his naval designs that enabled a Curtiss flying boat to fly straight and level without human interaction. In 1914, Lawrence, Sperry’s son and chief test pilot, went on to win a French prize of 15,000 gold francs for these demonstrations.

Could gyro-stabilization, when built into the right plane and given a sophisticated radio communication system, lead to an unmanned aircraft? The two inventors certainly thought so, and the Hewitt Sperry Automatic Airplane was born.

Inaccurate but Viable

Sadly, the Navy did not share the vision of the two men and initially rejected the idea. The aircraft was considered too inaccurate to effectively attack naval targets, and only after a great deal of lobbying by the two inventors were they persuaded to finance a prototype project.

The initial design was very simple. The plane would take off and fly in the direction it was programmed. After a certain distance, it would automatically release its bombs over where it hoped the target was, or else crash directly for maximum damage.

There were many external factors such as wind and weather which cold lead to the aircraft missing its target, and so as part of the design process a second type of plane was built. This second type allowed for wireless control from a pilot on the ground, which gave much better precision so long as the pilot could see the target.

After receiving final approval on May 17, 1917, Hewitt and Sperry received seven Curtiss N-9 seaplanes, with a order that six sets of the Sperry automatic control gear be fitted at a cost of $200,000. The project, based on Long Island, was underway.

It seems that the autopilot equipment was already designed and ready to go, but the radio control system hadn’t been fully developed. This aspect took up much of Sperry’s development time, although even after spending considerable money on patented radio devices to include in the plane it still had shortfalls.

The radio control systems he developed were not used on the Hewitt-Sperry Automatic Airplane, although it was installed on several Verville-designed planes in the 1920s, along with gear for the Army Air Services engineering division. These aircraft successfully hit their targets, proving that the system could be made to work.

Following this, practical testing for N-9 program started, and it quickly became apparent that a more efficient airframe was needed. Because of the ongoing war production, deliveries could not be diverted, but a special, rush order was placed with Curtiss in October, 1917.

A Problematic Aircraft

This order was for six planes of unique design, with an empty weight of 500 lb (230 kg), top speed of 90 mph (140 km/h), a range of 50 miles (80 km) and the capability of carrying up to 1,000 lb (450 kg) of explosives. They were known as the Curtiss-Sperry Flying Bomb.

- What Happened to Star Dust? The Plane Taken by the Andes

- The Philadelphia Experiment – What’s the Real Story?

It was to be a design specifically built around the remote control concept, and hence, the planes were not equipped with seats or standard pilot controls. Although Curtiss had no time for wind tunnel testing the first aircraft was delivered on November 10, barely a month after the order.

Initial design concepts had called for the plane to be launched from the sea, either by a catapult or under its own power. However this option was not available to the Flying Bomb, as it was not a seaplane. Instead, the designers tried to modify the catapult design and launch the craft by accelerating it down a long wire.

Three attempts were made in November and December 1917 to launch the Flying Bomb using this method. On the first launch, the plane hit the wire and one of its wings was damaged. On the second launch, the plane lifted free from the wire but then immediately plunged to the ground.

The wire method was proving unreliable and was abandoned in favor of a traditional catapult with a 150-foot (46 m) track, with power obtained from a 3-ton (2.7 tonne) weight being dropped from a height of 30 feet (9.1 m). However, this also led to problems in launching the plane.

On the third try, the plane again failed to launch, damaging the propeller flipping forward onto its nose. Two more follow-up attempts in January 1918 did result in the plane becoming airborne, but it was clear immediately that it had very poor handling characteristics. Too tail heavy, the plane crashed almost immediately.

Retrofitted with improve landing gear and room for a human pilot, Lawrence Sperry took the plane up himself to try to resolve the problems. After two crashes, and the use of a car driving while attached to underneath the plane to simulate a wind tunnel, improvements started to be made.

Sadly, by this time the plane was not required. With the signing of an armistice in November 1918, World War One had come to an end, and despite over 100 tests of the airplane there was now no need for the Flying Bomb. The Navy took over the research program, and the Curtiss-Sperry was never seen again.

Top Image: The Hewitt Sperry Automatic Airplane. Heavy on explosives, light on pilot. Source: Unknown Author / Public Domain.

By Bipin Dimri