Gaius Julius Caesar is, as a historical figure, not a straightforward proposition. The Romans with their confusing nomenclature didn’t help, of course, but despite their misleading efforts the man himself is something of a contradiction.

Here is a man who wrote thousands of words about his campaigns and his victories, but who we cannot entirely trust on depictions of either these battles or of himself. Here is a man who has been the subject of many descriptions, but almost always from a source with a hidden agenda.

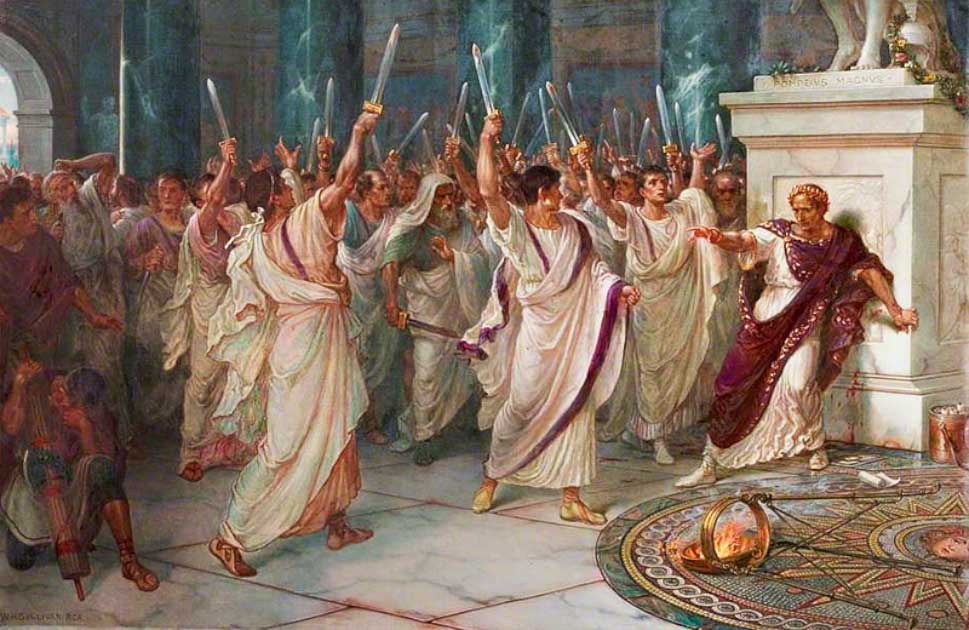

Here is Caesar, who was not himself a “Caesar” but who gave his name to the line of Emperors who came after. Here was a dictator for life, elected through the appropriate channels, who was murdered by the people who had elected him.

But, most pressingly, here is a master politician whose reputation rests not on politics, but on the battles he fought and won for the Roman Republic. His rise seems inevitable with hindsight, but what led to the senate seeing his support and help in the first place.

How did mighty Caesar win his reputation?

1. Siege of Mytilene

Caesar was born into an ancient and noble family, but one which lacked political influence. It was clear that scions of this house needed to find their own fortune, and so it was with Gaius Julius. He was an ambitious youth, and with the death of his father the head of his house at age 16, but it was as the high priest of Jupiter that he first attempted to make his way.

Happily family feuds saw him stripped of that role and allowed him to pursue a military path. Stationed under Marcus Minucius Thermus, who had been governor of Asia, Caesar first saw battle at Mytilene where he acted with distinction, earning himself the Roman “Civic Crown”.

- Mausoleum of Augustus: Why Are There No Tombs of Early Roman Emperors?

- Roman Concrete: Volcanic Material Created An Empire

Having gained the attention of his generals, Caesar was swiftly send on a mission to Bithynia to secure the aid of King Nicodemus. However, he was so long at the court of King Nicodemus that rumors started that the pair were having an illicit relationship, forcing Caesar back to Rome if only for the sake of his reputation.

2. Governor of Hispania Ulterior

Having returned to Rome (although he did manage to get himself captured and ransomed by pirates on the way), Caesar was free to pursue his political aspirations. It would be another fifteen years before he returned to his military career.

Having served as quaestor (a public official) in Hispania in 69 BC, he returned to the Iberian peninsula as governor of Hispania Ulterior, an area encompassing parts of modern day Spain and Portugal. There he acted to conquer the local tribes, earning the title “Imperator” from his troops.

Only if your troops had made such a proclamation could you apply for a “triumph” to be held in your honor in Rome, and so there may be a whiff of the political in this upswelling from the ranks. It also created a problem for Caesar, who wished to be Consul, the most senior senatorial rank, but could not while in command of his troops.

3. Gallic Wars, 58 – 51 BC

Caesar chose the consulship, denying himself the triumph as a military leader. However this was a canny political move and led to Caesar’s governorship of Gaul (modern day France), where he truly made his reputation.

With the help of his newfound political allies, with whom he formed the “First Triumvirate”, Caesar was given command of no fewer than four Roman legions, and installed as governor of a huge province stretching from the Balkans across the Alps to southern France. Caesar was also made consul (and thus immune from prosecution) for five years, rather than one.

When his term was up the ex-consul almost fled Rome lest he be prosecuted. With four legions under his command, Caesar set out to conquer ancient Gaul in its entirety. In a series of battles he took his well trained and numerous soldiers all the way to the English Channel.

4. Alesia

Caesar’s tactical masterpiece of the Gallic wars was undoubtedly Alesia. Besieging a Gaul stronghold and with a huge Gallic army approaching at his rear, Caesar created two rows of walls with his army between the two, both attacking the town and defending from outside sallies.

The Battle of Alesia in 52 BC, against the confederation of Gallic tribes under their chief Vercingetorix, was the final battle of the war. The defeated chief famously threw his arms at Caesar’s feet and all Gaul was won for Rome.

Alesia fell to the Romans and was converted to a Roman town. However, after it was abandoned during the decline of the Roman empire in the following centuries, the location of Alesia remained unknown for a long period of time.

5. As Dictator

It was Caesar’s successes in the Gallic Wars (as covered in glowing terms by Julius Caesar’s publications on how great he was) which won him his reputation. Favored by the army, Caesar felt powerful enough to refuse when Rome called for him to disband his legions and return as a private citizen.

Caesar’s decision to cross the Rubicon and enter the Italian territories in force, something strictly forbidden, was not as wild and impetuous as it might seem. His battle-hardened forced were superior to the green levies raised by Rome, and Caesar was in a position to do what he wanted.

First as an emergency dictator, and then (briefly) as dictator in perpetuity, Caesar used the reputation he had built for himself and the love of the soldiers to position himself as a dictator at the head of the Roman Republic. In the end even his death could not prevent the fall of a democratic Rome.

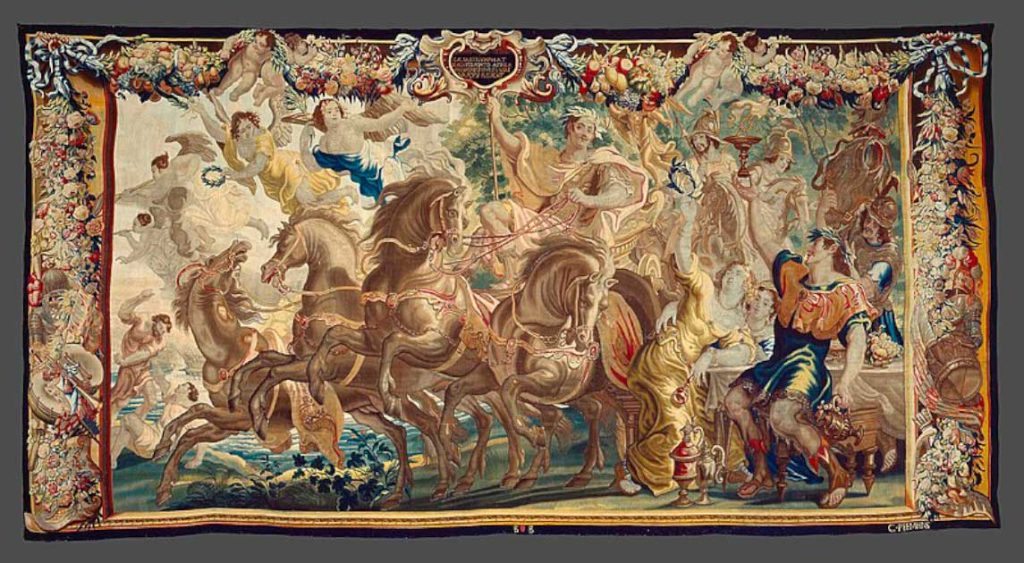

Top Image: Gaius Julius Caesar was famed for the battles he won, but it was his political contacts who gave him the impetus he needed. Source: FrDr / CC BY-SA 4.0.

By Joseph Green