“Knighthood lies above eternity; it doesn’t live off fame, but rather deeds.” – the Serbian poet and philosopher Dejan Stojanovic.

Invasion, monarchies, and the feudal system all were attributes of the Medieval Ages, an era marked by frequent warfare. Among the invaders that the realms had to fear were the Vikings, Saxons, and warlike Magyars from the east.

Who would fight to protect sovereignty, maintain the peace, and ensure power remained in the hands of those who sought it? The medieval knight assumed the role of protector of the realm. But what did it take to be a medieval knight?

What was a Medieval Knight?

If you think a man grows up and then decides he wants to be a knight, you’re mistaken. This pivotal decision is made in the boy’s early childhood.

To be considered for such an honorable role, a number of critical qualities must first be possessed. The boy must be of high birth, which not only implies that he is honorable, but also that he has enough money for his weapons and armor. Prior knowledge of chivalry is required, as this is the code by which he will live after being knighted. He will begin his training around the age of seven if all these prerequisites are met.

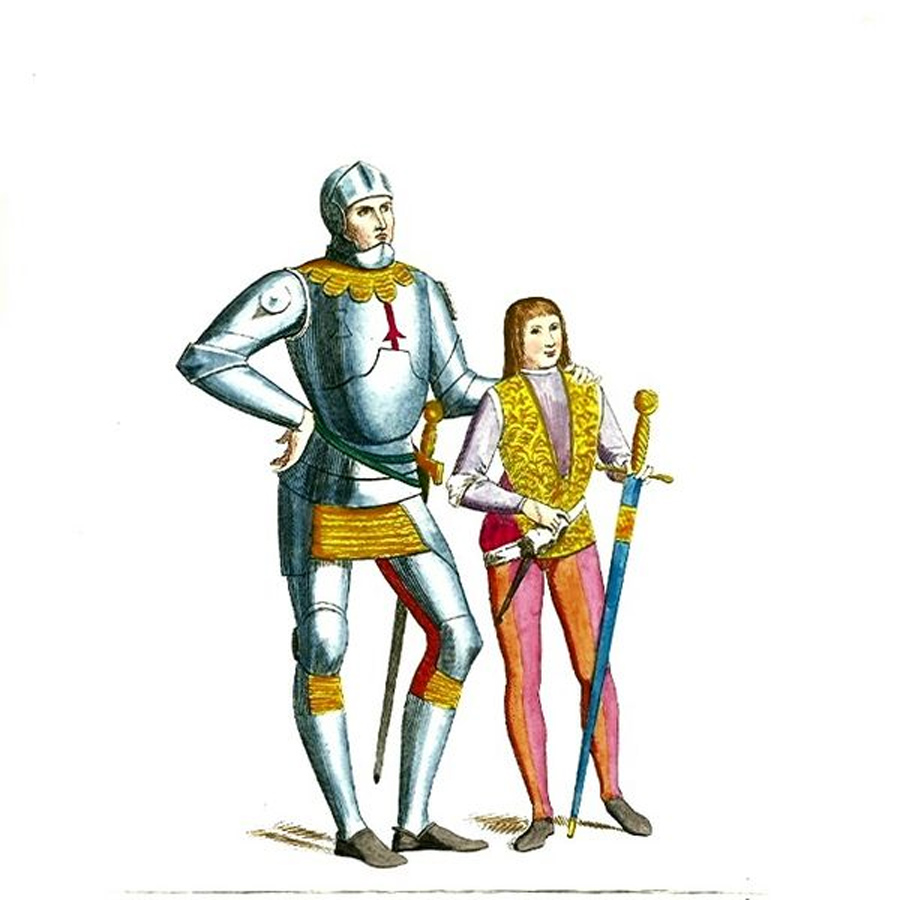

As part of his apprenticeship, the aspiring knight will assist an acting knight in the role of a “page” and later as a “squire”. During his years as a page, the boy will learn about horse care, riding, and, most importantly, hunting. He will be advanced to the post of squire by the age of fourteen, which includes weapon training and lectures in chivalry.

- Götz von Berlichingen: How a One-Armed Knight Rose to Power

- Was King Arthur Real? Examining the Historical Record

On the battlefield or in concerns of war and peace, he will take on greater responsibilities to assist the knight he serves. Then, around the age of eighteen, he will be evaluated to see if he is worthy of becoming a knight.

The “damoiseau” (lording) ceremony is the name given to the ritual in which a squire is appointed to the rank of knight. The scale of the ritual varied depending on the status of the soon-to-be knight or the current state of affairs (peace or war). The more wealthy knights were sent to bathe the night before the event, which was an unusual practice at the time.

On the eve of his knighting, the knight would hold a “vigil,” according to tradition. He had to spend the entire night kneeling in front of an altar where his weapons were kept. This vigil would be performed fully clothed in his armor, which would be a test of strength and endurance.

When the monarch or someone in a high position placed a sword on his shoulder and struck him with an accolade, the knight was officially commissioned. The final words spoken to the newly knighted soldier were, “Be thou a knight.” And thus, his oath of fealty – to God, his monarchy, and the people of his country – would begin.

An Honorable Duty

To comprehend the role of a knight, we first should consider the four tiers of the feudal system. The kings (rulers of the realm, who may or not be royalty) are at the top. The nobles, the lords and ladies, are next, followed by the noble knight, and finally the peasants and serfs.

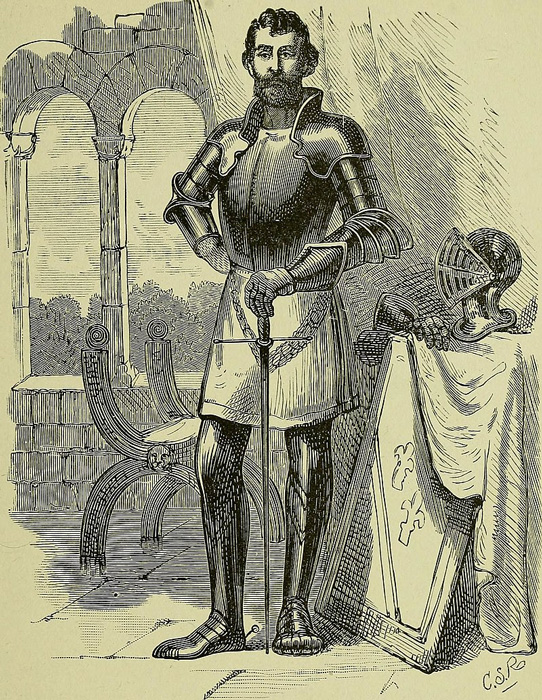

A knight was first and foremost a professional warrior. Knights were hired by lords or monarchs and would march the lord’s armies into battles. Some of the more successful knights would acquire quite a fortune.

If they were the right sort and could present themselves as aristocratic, or had high-up connections, maybe they would serve a ruler or royalty. These positions paid well as they were providing protection to the most important people in the realm. Others would compete in hunting or jousting competitions for monetary or material rewards.

- Did Knights Templar Hide the Holy Grail in Iceland?

- What Can We Know about the Poet Who Wrote Gawain & the Green Knight?

Knights were given a “fief” once they were anointed, this would be enough land to support their families and laborers. Any surplus land was rented off to peasants and serfs, providing the income needed to maintain their high-end lifestyles.

Often this money would also be used to pay a “scutage”, a frequent practice that emerged towards the end of the Middle Ages. Medieval knights could pay the king a fee to be excused from fighting and entrust the perilous duties of war to soldiers.

Was the knight as brave or as treacherous as fairy tales portray him to be? Apparently not, for by the 13th century, over 80% of knights in England were paying scutages to avoid combat. At this point, the knight was essentially an extension of the feudal system, a position that contributed to the maintenance of hierarchy and social order.

The Courtly Knight: Only a Myth?

In Medieval European literature, “courtly love” was a common motif. A term used to express a knight’s love and respect for his lady. His affection and loyalty were pledged to her. He was in charge of his decision, but he was also obligated and bound by it. He would go to the farthest extremes in his lifetime service to her.

So yes, in certain ways the courtly knight was a real figure, as seen by the courtly knight’s devotion to his king and the realm he serves. His honor was bound by his service as a knight. In practice, this may or may not have been honored by all knights.

Some medieval knights were known to be bandits or hired mercenaries who are more concerned with money and power than with the noble functions that came with the posts. Most likely, the courtly knight we read about in literature was a fabrication or fiction designed to aid in the control and shaping of social conduct.

Protectors of the realms, courtly gentlemen, or just high-born men with a proclivity for social standing and lavish living? The path to becoming a medieval knight was unquestionably one of commitment and perseverance. The only question, if there even is one is, how brave these men were, men who are frequently depicted as heroes in fables and myths.

Top Image: The life of a knight was one of privilege, but also danger and hard work. Source: EyeEm / Adobe Stock.

By Roisin Everard