Britain in the Second World War faced possibly her greatest domestic challenges by air. Much of the credit for her successes in stemming the Nazi aggression and eventually taking the fight to the Germans must come from the brilliant people who designed her aircraft. But much more credit must go to their knack for adaptation, and innovation.

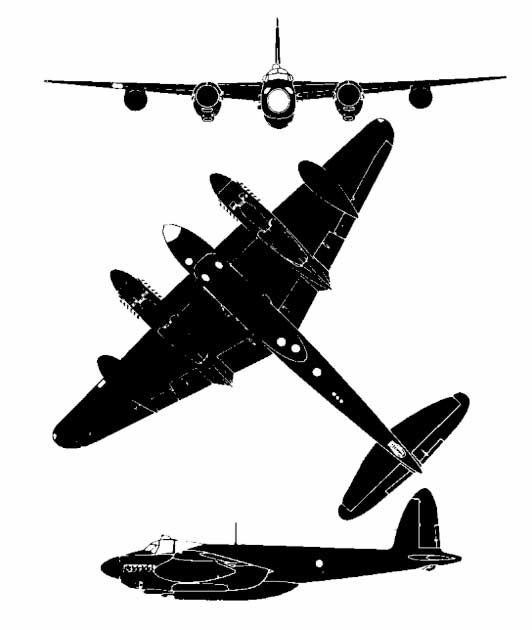

This is certainly true of one of the most remarkable aircraft built during the years of the Second World War: the Mosquito. Designed as a fast bomber, mostly made of wood and originally with no air-to-air armament at all, she somehow turned out to be one of the truly great fighter planes of the war.

She was nicknamed “The Wooden Wonder” because of her speed and unexpected agility in the air. She was almost never built, requiring the intervention of the British Air Chief Marshal, Sir Wilfrid Freeman, who defended the concept design. In 1941, she was recorded as the fastest aircraft in the world.

How did a bomber beat the fighters at their own game?

Development of the Mosquito

The original designs for the Mosquito in 1936 were for her to be a fast bomber. However, these soon evolved and became adapted to many roles. Able to fly at low-medium altitudes, the Mosquito could be used as a day tactical bomber or even, at a push, a night-time high-altitude bomber.

In addition to these roles, she could be used as a pathfinder, as a maritime striker able to quickly respond and hunt down enemy shipping, and a photo reconnaissance plane. The British Overseas Airways Corporation would also utilize the aircraft in a non-military capacity to transport small, high-value cargo to neutral countries that were being restricted by enemy-controlled airspace. It allowed for one pilot and one passenger.

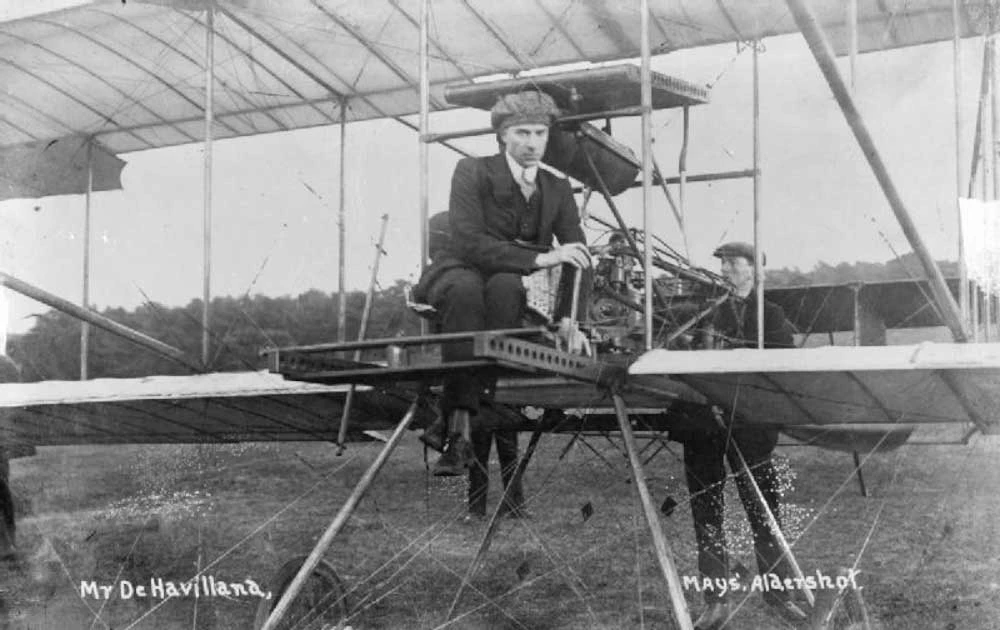

Geoffrey de Havilland came up with the design for this aircraft in the 1930s. A true aviator of the old school, by midway through the 1930s, he had established a reputation for high-speed aircraft with innovative designs.

- The Nazi V-3 Cannon: Could this “Vengeance” Weapon Have Destroyed London?

- Yamamoto: How did the U.S. Manage to Kill the Legendary Japanese Admiral?

He had designed and created the DH.88 Comet racer which set many record times for long-distance flights both in racing and on record attempts. He developed this idea by designing the DH.91 Albatross which was mostly made of wood. This feature, seen as oddly anachronistic by many of his contemporaries, would be passed on to the Mosquito.

The Albatross could hold 22 passengers and could fly at around 210 miles per hour (338 km/h) and reach an altitude of 3,400 meters (11,150 feet). It was faster than any other plane of its type, and De Havilland discovered that the wooden construction not only saved weight but compensated for the lower-powered engines used in his aircraft. He used the lower power engine because they were easy to mass produce and construct.

Geoffrey’s success with the Albatross led him to believe that a bomber with a good aerodynamic design and minimal skin area would surpass the specification for bombers set by the British Air Ministry. In 1938, de Havilland began to create a prototype using the Rolls Royce Merlin-powered engines.

Success with these initial designs led him to write to Air Marshall Wilfrid Freeman explaining that wood would be a better option for bombers, as aluminum and steel shortages would occur during war, but wood would remain quite plentiful.

History of Operations

The first produced Mosquito, the W4051, was sent to a Photographic Reconnaissance Unit. It was set to begin taking secret photographs in July 1941 at 6,000 meters (20,000 feet). It was not until November 1941, that the RAF at Swanton Morley, Norfolk took in the first operational Mosquito bomber, the W4064.

Through 1942, they undertook low-level and shallow dive attacks. They were mainly used on industrial and infrastructure targets across Netherlands and Norway, but they were also used on targets in Oslo and Berlin. The pilots and crew praised them for their handling, their speed and their flight characteristics.

While on duty the aircraft came up against flak fighters called Snappers. They often found themselves in German airspace and were often at a disadvantage. However, during the fights, Mosquito pilots were able to make the most of their excellent handling capabilities to escape from danger. This was more useful than its speed when evading the enemy.

- The Largest Aircraft in WW2: What happened to the “Gigant”?

- The Kugelpanzer: Why Did the Nazis Build a Spherical Tank?

The Mosquito was not announced publicly until September 1942. It was after a raid in Oslo on the 25th of September and recorded in the Times on the 28th of September. They also participated in Operation Oyster which was a raid against the Phillips works in Eindhoven, Netherlands.

As the war progressed, Mosquito bombers continued to fly at high speeds whilst low and medium altitudes during the day to engage with infrastructures like factories, and railways and pinpoint targets across Germany and its conquered lands. As a fighter she excelled as well, with the twin engine design allowing space for four machine guns directly ahead of the pilot, improving accuracy.

In 1943, the Mosquitos were formed into a Light Night Striking Force to help guide the RAF Bomber Command raids and to become nuisance bombers that caused chaos and destruction across the German targets. They became so effective that by the end of the war and on their last official European War engagement in 1945, they continued to hunt German submarines. The last ones that were active were not retired until 1963 and had been used by the Number 3 Civilian Anti-Aircraft Co-operation Unit.

The Variants of the Mosquito

Due to the success of the original model, there were many different variants created. From Mid-1943, variants began to be made to make them more suitable for different operations. The NF XII was designed to carry AI radar which introduced a spinning dish scanner to aircraft for the first time. This took over the space that was previously occupied by 4 machine guns.

Production was not limited to Great Britain, and the commonwealth also began to build these. The F.B. 26 variant was created by Canada and Australia also built a variation named the FB 40 which had engines that were heavier but more powerful. In all, no fewer than 27 different versions of the Mosquito were created and taken into service. They were particularly useful in carrying larger loads over long distances.

The Mosquito utilized a more traditional material to create a useful and durable aircraft. Whilst other nations focused on metal production, Britain focused on wood. The Mosquito aircraft participated throughout the war and played a part in some of the largest and most significant operations that occurred.

This included large raids across Germany and even playing a role in the Battle of Britain and D-Day. There are around 30 aircraft that still exist today though none are airborne. In order to see one, many of them are housed in the de Havilland Aircraft Museum in the UK.

Top Image: The de Havilland Mosquito, here fitted as a bomber with a clear Perspex nose for the bomb sight. Source: Royal air Force official photographer / Public Domain.

By Kurt Readman