Between 1946 and 1991, the United States, the Soviet Union, and allies on both sides were locked in a long, drawn-out conflict known as the Cold War. The nuclear arms race was becoming aggressive, and there was a constant threat of nuclear attack from both sides.

This constant threat of sudden nuclear destruction impacted how regular citizens lived. Bomb shelters were built, children practiced duck and cover drills in school, and the terror of not knowing when nuclear attacks were coming made both the Soviet Union and the US even more hostile towards each other.

During the Cold War, gaining intel on the opposition was highly sought after, and things like double agents, defections and information releases, and wiretaps were common. One of the most interesting wiretaps, Operation Ivy Bells, occurred deep undersea in Soviet-controlled waters.

Operation Ivy Bells

Operation Ivy Bells was a joint mission between the National Security Agency (NSA), the United States Navy, and the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) to apply wiretaps to Soviet underwater communication lines during the early 1970s. During the Cold War, the United States was desperate to gather any information it could about the missile and submarine technology that the Soviet Union had and was further developing.

The United States was most concerned about intercontinental ballistic missiles (ICBM), which have a range of more than 5,500 km (3,400 miles) and were designed for nuclear weapons as well as conventional, biological, and chemical weapons. Along with the threat of ICBMs, there was the genuine threat of first-strike capability on the side of the Soviet Union.

First-strike capability is “a country’s ability to defeat another nuclear power by destroying its arsenal to the point where the attacking country can survive the weakened retaliation while the opposing side is left unable to continue the war.” The risk of one side getting a knock-out punch in first was a constant worry for both superpowers.

- Operation Satanique: When France Bombed Greenpeace

- Project Azorian: Did Howard Hughes Try to Steal a Russian Sub?

Operation Ivy Bells came about because the United States learned that there was an undersea communication cable that connected the Soviet Pacific Fleet base in Petropavlovsk, which lies on the Kamchatka Peninsula, and the Fleet’s main headquarters in Vladivostok (a distance of over 2,250km [1,398 mi]). The cable ran across the Sea of Okhotsk, which was part of Soviet territorial waters, and foreign vessels were not allowed into the sea.

The US needed to hear these communications, and to do so they needed to tap the cable. But entering the Sea of Okhotsk was dangerous, and the Soviet Navy had placed an extensive network of sound detection devices along the seabed to detect any intruders entering below the water. Operation Ivy Bells was too critical for the US to simply drop, however: a solution had to be found.

The Installation

In October 1971, a modified submarine, the USS Halibut, was sent into the depths of the Sea of Okhotsk. Operation Ivy Bells was so classified that most of the sailors who took part in the operation lacked the security clearance required to know about it.

This meant a cover story needed to be created, and the US claimed they were there to collect the debris of the Soviet SS-N-12 Sandbox, a supersonic anti-ship missile (AShM), so the US could develop countermeasures to protect its ships in the future. In the event, the retrieval of the SS-N-12 Sandbox was successful, and more than two million pieces and fragments were collected and sent to the US Naval Research Laboratory. The missile was able to be reverse-engineered: the mission was a success even without the cover story aspect.

The divers in the USS Halibut who were there to work on Operation Ivy Bells were able to locate the communication cable at a depth of 120 m (400 ft) and a 6.1 m (20-foot) long device to the cable. The device was designed to wrap around the cable without puncturing its casing and was able to record all communications made over the line. A large recording device was attached to the cable and was explicitly designed to detach from the cable if it was raised for repair or maintenance.

Every month divers were sent to retrieve the recordings and install new sets of tapes. The taped recordings were taken to the NSA to be processed before being sent to the other agencies involved in Operation Ivy Bells.

Ironically, the US learned that the Soviets were positive that the cable was so secure they felt no need to encrypt their messages. Other valuable information gathered from the tap included intel on the naval operations at Petropavlovsk. This was important because it was the Navy’s main nuclear submarine base, and two nuclear-powered ballistic missile subs were kept at Petropavlovsk.

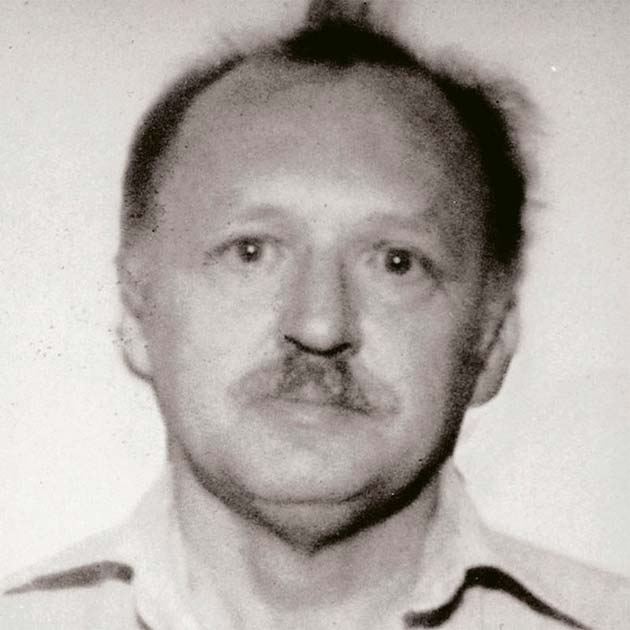

Ronald Pelton

Operation Ivy Bells was compromised by a man named Ronald Pelton in 1980. Ronald worked for the NSA for 44 years and was fluent in Russian; the issue was that he was in debt.

- Operation Hurricane: Britain’s Desperate Bid to be Third

- Did the CIA Really Have an Inflatable Plane?

He was $65,000 in debt and had even filed for personal bankruptcy three months before resigning from his NSA job. Finally, in his desperation, Pelton went to the Soviet embassy in Washington, DC, and offered to sell information to the KGB for a price.

The KGB reportedly gave Ronald Pelton $35,000 for the intelligence he gave to them from 1980-1983. For providing information to the KGB about Operation Ivy Bells, he was paid only $5,000 for this top secret information.

Even though the Soviet Union now knew about the cable being tapped, they waited until 1981 to do anything about it. Then, unexpectedly, US satellites detected Soviet ships, including a large salvage vessel, anchored directly on the site of the tap.

The US launched the USS Parche to retrieve the device, but they could not find it. It was assumed the Soviets had managed to get to the device before the US could. In fact the US had no idea that Robert Pelton had sold information about Operation Ivy Bells until July 1985.

Vitaly Yurchenko, a KGB colonel, was Pelton’s original contact in DC in 1985. Yurchenko defected to the United States and provided information about what Pelton had done. This led to Pelton’s arrest, and because the crime was in direct violation of the Espionage Act of 1917, he was severely prosecuted.

To see the wiretap and recording device the US used during Operation Ivy Bells, you can visit the Great Patriotic War Museum in Moscow, Russia, where it has been on display since 1999. The museum has the most extensive collection of objects and ephemera from WWII in the world and is 100% worth a visit if you are ever in Moscow.

Top Image: Operation Ivy Bells was a complete success, even down to the goals of the cover story, until it was betrayed for a mere $5,000. Source: Jesper / Adobe Stock.