Collecting seems to be a human fascination, and the desire to acquire, maintain, organize and display specific items reaches far into the past. People have been collecting since the beginning of time, and it is because of collecting that we have museums like the Louvre in Paris.

It isn’t just art museums that collectors’ passion has been able to establish. Many botanical gardens come from specimens donated to the institution by dedicated botanists. One of these fantastic botanical gardens is the Kew Gardens in southwest London. Among the bright and beautiful blooms is an extensive collection of orchids.

These orchids are a remnant of the past and a trend that swept through Victorian England. It was a trend that was so prolific that Kew Gardens continues to work to prevent the extinction of rare and exotic orchids.

But it seems the Victorians took it too far. The upper class in the 1800s often became obsessed with orchids, a condition referred to as “orchidelirium”. The condition led to a greater understanding of gardening, to be sure. However, the passion for collecting orchids became so intense that people did whatever they could to have the best of the best.

Many people’s losses of fortunes and lives have been attributed to orchidelirium, and it is still occurring to this day. What was orchidelirium, and why was Victorian England so passionate about orchids?

Orchidelirium

Orchidelirium refers to a time in the Victorian era (the 1800s) when people were obsessed with collecting and discovering rare orchids. Orchidelirium was very similar to the “Tulipmania” phase that captivated Holland.

The Orchidaceae family is one of the largest of all flowering plants, and there are around 27,000 different species that exist today. Each year the number of species grows as hybrid variants are produced and added to the taxonomic family. Only one percent of orchid species can be found in Europe, and a large majority of wild orchid species grow in the tropics and subtropics.

Yet, orchids, for all their exotic bona fides, are surprisingly hardy and adaptive plants. They can be found on every continent except Antarctica. They can exist at high altitudes, semi-desert, and tropical conditions.

What made orchidelirium so consuming during the Victorian era was that the flowers desired most were not meant to be grown in England. The cold and temperate weather is not suitable for flowers that are found in nature in South America.

Getting an orchid in your possession was one thing; keeping it alive and reproducing was another. The wealthy had the means to obtain and care for the plants. The more greenhouses and nurseries filled with orchids someone had, the more affluent and refined that person was.

Keeping Up with the Victorians

The common legend associated with the start and spread of orchidelirium runs as follows:

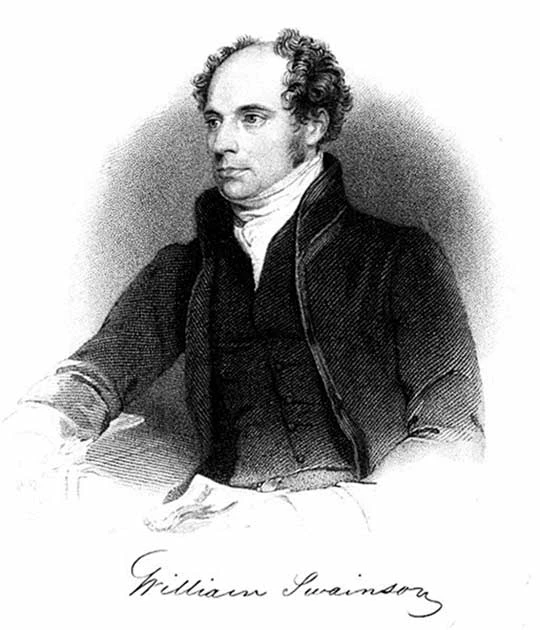

“In 1818, William Swainson sent several plants from Brazil to London using what he believed were parasitic plants as packing material. When the package arrived in London, one of the plants was in bloom. Its vivid hue and strange shape were unlike anything most European eyes have ever beheld in the way of flowers. Europe fell in love. And soon began orchidelirium, the European obsession with orchids.”

- Why did Pineapples Become a Status Symbol in 18th Century England?

- Boy Jones: Peeping Stalker of Queen Victoria

The truth, according to scientists at the Smithsonian Environmental Research Center, was that Swainson, a biologist, most likely knew that the “parasitic plants” were, in fact, orchids. He recognized their value when he shipped them to Europe, and people were amazed by the plant.

Orchid cultivation was not a new concept. Since the middle ages, Europe has collected or sought out orchids. The popularity of the orchid was nothing compared to the obsession that occurred in the 1800s.

The rich could afford to collect orchids; they were associated with royalty and privilege. The upper class became infatuated with obtaining rare species and would do anything to own the largest and most diverse collection they could amass.

At the peak of orchidelirium, a single orchid would sell for over £200 (today, that would be around £25,000 or $29,000). The constant swings in supply and demand only made the prices for orchids sold at auctions reach astronomical levels.

While someone could buy a single orchid at an auction, many would be sold in lots of 100 or more and cost a fortune. An example of how collectors could trade and sell plants to others for large sums of money is the tale of a collector who purchased an orchid from another collector for £12. Five years later, he sold the same flower back to its original owner for £1,000.

The markup was solely due to the desirability of the orchid in question according to the vogue of the time: the underlying plant had not changed in appearance, availability or rarity. Orchidelirium, while undoubtedly a job stimulus for the Victorians, was a speculative bubble in its purest form.

The Orchid Hunters

Wealthy orchid collectors would hire men to go all over the globe and retrieve rare species of orchids and bring them back to England. Frederick Sander, the “Orchid King,” employed 23 hunters and built more than 60 greenhouses to cultivate and sell his collection.

A greenhouse in Victorian England was no small undertaking, and Sanders was such a prolific collector that in 1886, he was given the official title of Royal Orchid Grower to Queen Victoria. The wealthy, struck with orchidelirium, would finance costly orchid hunting trips so the hunters could find the flowers for them. Why go trekking through forests in foreign lands when you can just pay someone else to do it?

There were “free agent orchid hunters” who would spend months abroad collecting every orchid they could find just to bring them to auctions and make a fortune. Not all orchid hunters were honest men, and many would take advantage of their wealthy employers.

Historians have found accounts from supposed “orchid hunters” who took the money and would live the highlife in Paris. When the funds got low, these men would buy a few common orchids and bring them back to England and pretend they “found” the plants on their trip.

But for those who would not commit fraud, orchid hunting was a dangerous and deadly profession. Hunters had to deal with tropical diseases, wild animals, thick and treacherous terrain, angry indigenous populations in the hunting grounds, and other orchid hunters.

- How the Darien Scheme Changed the History of Scotland’s Independence

- The Great Stock Exchange Fraud: Lord Cochrane’s Napoleonic Lies?

One of the Orchid King’s hunters, William Arnold, got into a fight on a ship headed towards Venezuela with another hunter, and the men pulled guns on each other and almost started a shootout. When news of the ordeal reached the Orchid King, he instructed Arnold to follow the man, collect the same flowers he did, and then urinate on the man’s specimens to destroy them.

Orchid hunters would return from their expeditions with stories about other hunters stealing specimens from rivals or being held up at gunpoint by another hunter to find where one specimen could be found. On several occasions it seems the competition to find the rarest orchid even turned deadly.

The number of orchid hunters who died due to orchidelirium is unknown. There was a story of a team of eight hunters who went on an expedition to the Philippines and encountered many dangers. One party member was burned alive by natives, and one was mauled by a tiger. Five men went into the jungle and never returned, their bodies never found. The sole survivor however finished his job, and was paid handsomely for the species he brought back.

Valuable Species

Any rare orchid was valuable to both sellers and collectors. Some of these orchid species included the stunning blue colored Vanda Caerula, which sold for £300 pounds (£40,500 or $46,000 today). From Java, orchid hunters brought back the Vanda Tricolor, which has pink and yellow flowers with brown spots.

The moth orchid, Phalaenopsis Amabilis, was also sought after because it was easy to cross-breed with other species to create hybrids. The rare ghost orchid, Dendrophylax Lindenii, was found in Cuba and the everglades of South Florida.

People to this day are still willing to do what they can to get their hands on the rare ghost orchid. For some, orchidelirium never went away. But, as with ll bubbles, eventually the mania passed and prices collapsed.

The main problem was that during orchidelirium, collectors had little to no knowledge of growing the flowers once they were brought back from hunting expeditions. A collector would receive orchids, which would bloom for a while, but then they would not flower again or die.

Through experimentation, botanists discovered how to grow plants from seeds. By the 1920s, exotic blooms could be produced, which decreased the prices of orchids. But this was not before orchidelirium resulted in the extinction of some species of orchids. They were removed from their native habitat and brought to people who knew nothing about how to care for the plants.

Orchidelirium and the all-consuming desire for the rarest blooms devastated the native orchid population in many places. There are still areas in Central and South America where the natural population of orchids has never recovered from orchid hunting from the Victorian era.

The international trading of orchids harvested from the wild has been banned by the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora (CITES) since 1973. Even though orchid hunting is illegal, orchid smuggling is still occurring.

The true scale of how many smuggled orchids are bought and sold illegally is unknown due to its secretive nature; it is believed to be why specific orchids have become endangered or at risk in the wild. Orchidelirium is not as rampant today as it once was, but the fascination with these flowers still inspires study and cultivation in backyards.

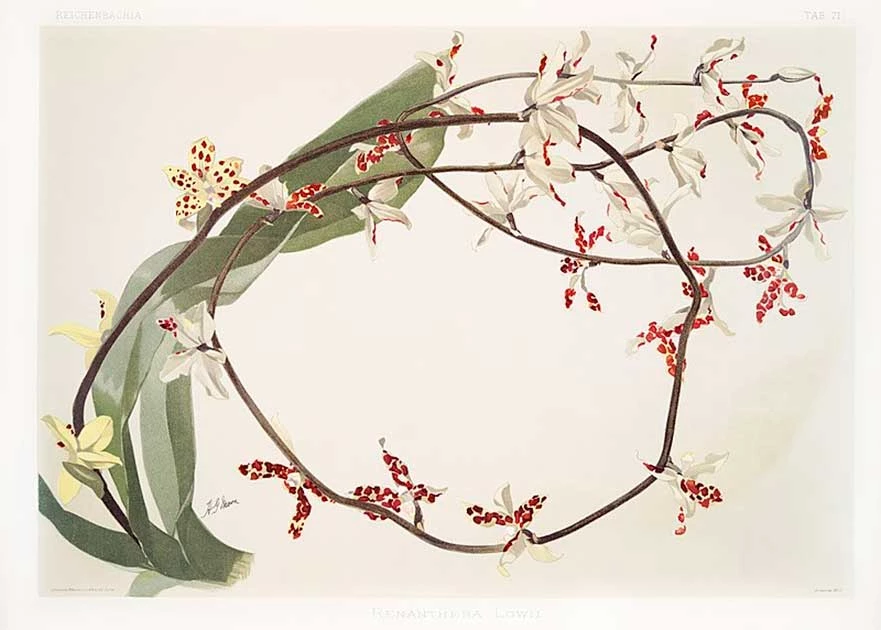

Top Image: Orchid illustration by Frederick Sander the Victorian “Orchid King”. Source: Rawpixel / CC BY-SA 4.0.

By Lauren Dillon