Samuel Pepys (1633 – 1703) was an important man, but that is not what he is remembered for today. An English naval administrator, he served in the Royal Navy went on to become a member of parliament.

However, he is perhaps most famous for his diary that he kept for around a decade of his life. It has been described as a unique literary work, and perhaps what makes it so special was that it was not written for publication like many other diaries created at this time.

It thus gives an uncensored insight into life in London during the tumultuous time of the Restoration after the civil war in the 17th century. It is known that this diary was not due for publication because he wrote it in code. Why did he do this? And what was he trying to hide?

Samuel Pepys: His Life

Samuel Pepys was born in 1633 in London. He was one of eleven children, but of only three that survived to adulthood. He did not have a rich family. His mother was the sister of a butcher, and his father was a tailor who struggled to collect money from his services.

The family however was not completely poor. Pepys was related to Edward Montagu, the Earl of Sandwich and they grew close over the years. And in London at the time, having a rich benefactor could set you up for life.

He went to school in St Paul’s in London, studying whilst the English Civil War decided the fate of England around him. He was even witness to the beheading of Charles I in 1649, as a 16 year old. He later attended Cambridge University where he received his degree. By the age of 22, he had married the 15-year-old Elizabeth Marchant de St. Michel, a poor refugee from France. Upon his graduation, he went to work for Montagu.

- Dictys of Crete: Was There a War Reporter at the Siege of Troy?

- The Glorious Revolution: Did the Dutch Steal the English Crown?

Montagu hired the 17 year old Samuel in 1660 to be the secretary for the Admiral on a voyage to Holland, where he was party to escorting Charles II back to England for the restoration. When he returned, Pepys was employed by the Navy Board as the Clerk of the Acts.

He was responsible for naval supply distribution and acted as a justice of the peace. He was quite successful in this role and moved up the ranks. He was in this position when the Great Plague struck in 1665 and the Great Fire of London in 1666.

Sadly in 1669, Pepys wife died of fever. He continued working with the Navy and in 1673 he was promoted to be the secretary of the Admiralty Commission. He was also elected as the Member of Parliament for Castle Riding in Norfolk. Pepys advocated for new ships and stomped out the corruption of the supply yards. He retired in 1689 before dying in 1703 where he was buried next to his wife.

What was in the Diary?

Pepys started his diary on the 1st of January 1660 (for those keeping score, this is also the year Daniel Defoe, author of Robinson Crusoe, the world’s first novel, was born). He gives a summary of the events that were taking place in England. He discussed the defeat of Oliver Cromwell and the plans for the restoration of the monarchy. Charles II was in exile in France at the time, and Pepys records how his employer, (and his cousin), Lord Montagu wanted him to go with the fleet to retrieve Charles II.

Pepys continued to document his daily life for nearly a decade. The diary itself is more than a million words long and is celebrated as one of the most influential literary works. His frankness in writing especially concerning his own weaknesses and how he accurately describes the events makes him one of the great writers of the 17th century. He wrote about the court and its goings-on but also about the theatre and his affairs with the actresses.

Historians have been able to use his diary to get an insight into 17th-century London. He wrote on subjects like his personal finances, when he got up in the morning, the weather, and even what he ate. There are very human moments in the diary also, such as his excitement at his new watch which included the new alarm feature. He also wrote about visitors to London and what they thought of the city.

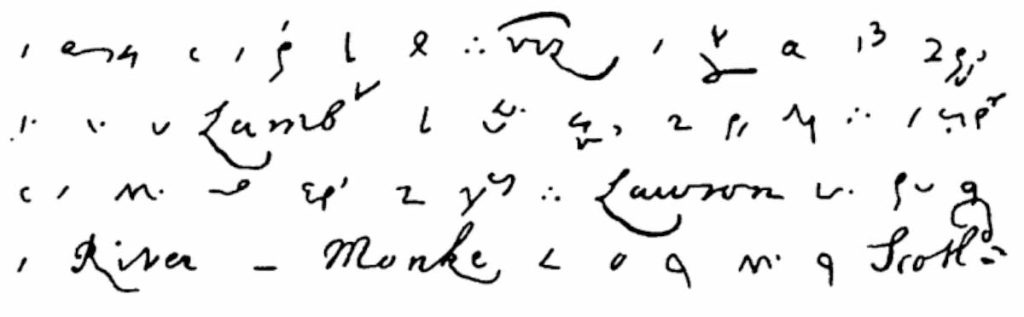

Samuel Pepys did not plan on his diary ever being published and read. He wrote it in code, a form of shorthand of his own and which, perhaps, allowed for a frankness he would not have exhibited had he written in plaintext.

- A Death in Deptford: Who killed Christopher Marlowe?

- Sir Francis Bacon: King James I’s Man of Science

Writing in Spanish, French, and Italian, he often juxtaposed these passages with profanities in English which gave away some meanings of the passages. He may indeed have intended for future generations to read it eventually but probably did not think it would reach the levels that it has. He certainly ensured it was preserved however, donating the diary to the library at the University of Cambridge.

One of the most fascinating aspects of the diary is that it reveals all of his secrets and vices. It describes the women who he pursued, the friends he socialized with, and his insecurities and trivial concerns. He drifts between big political machinations and his own life and the mundane, following whatever interested him at the time. As a personal account it is almost without rival.

Pepys diary stops in 1669. He wrote about how his eyesight was beginning to fade and that he was concerned that writing in dim light damaged his eyes. He toyed with the idea that someone else could write it for him but feared he would not be able to be as open.

He lived for 34 more years but sadly these years were not recorded. Instead, he focused on his employment with the Navy Commissioners. Though he did keep another diary when he visited Morocco it was substantially smaller and more scheduling and work-notes than the candid confessional of his earlier life.

Samuel Pepys

The diary written between 1660 and 1669 gives a true insight into London life for a writer in the 17th century. Few other contemporary pieces of evidence are of a similar nature. It was not published until 1825 when Lord Granville labored over the translation of the diary for many years.

It has since been revised but the first edition had omitted passages that they deemed too obscene. This was often to do with his illicit affairs. It has since been translated and put online so that everyone can read it. It truly is a marvelous literary work that shows real emotion and gives a snapshot of the 17th century.

Top Image: Pepys’s Diary is considered one of the most revealing sources for 17th century London we have. Source: Wellcome Trust / CC BY 4.0.

By Kurt Readman