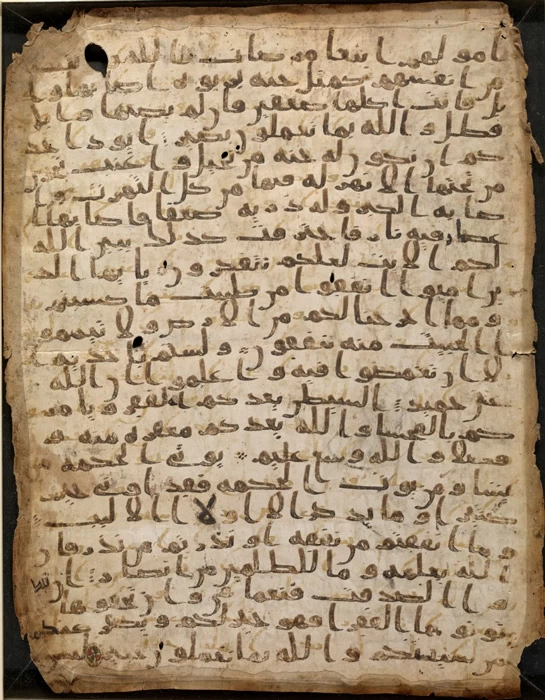

The Sanaa Quran is one of the oldest Quranic manuscripts that still exist today. Part of a sizeable hoard of Quranic and non-Quranic materials found in Yemen in 1972, the manuscript was discovered during the restoration of the Great Mosque of Sanaa.

When studied, the manuscript was confirmed to be a palimpsest Quran. This means that the text was written on a piece of parchment that had already had writings on it, not uncommon given the scarcity and expense of parchment.

The upper text found on the manuscripts, and therefore the most recent, was identified to conform to the standard Quran compiled by the companion of the Prophet Mohammed, Uthman. The order and size of the chapters matches what is found in the Quran today.

The lower text could only be read through the use of ultraviolet light, as it had been erased and overwritten. This text, hidden underneath the standard wording of the Quran, was different. It was still the Quran, but the phrasing was not the same.

The Quran, as the word of Allah, is supposed to exist in one standard, perfect form. Unlike the Bible, all Qurans are supposed to be exactly the same. The existence of a different version of the text, therefore, is a great puzzle.

Did God dictate two Qurans? Or could the text have been altered by human intervention before its publication, leaving imperfections in the perfect Word of God? Neither was an appealing conclusion for the scholars of Islam.

Discovery and Restoration

During the renovations of the Great Mosque of Sanaa in 1972, construction workers were renovating the attic. They came across large quantities of deteriorated material in the attic spaces which were revealed to be old manuscripts and parchments, hidden away.

With no idea of the significance of the find, the workers packed the parchments into potato sacks and stored them on the staircase of one of the minarets.

Fortunately, the president of the Yemeni Antiquities Authority heard about the find and knew the potential importance of examining the manuscripts and thus saved them. Qadhi Isma’il al-Akwa, after saving the manuscripts, sought international assistance in preserving the various fragments and in 1979 managed to interest the West German government in organizing and funding a restoration project.

- Why was the Infancy Gospel of Thomas Excluded from the Bible?

- Oxyrhynchus Papyri: Historical Treasure in Ancient Egyptian Garbage

The project began in 1980 under the supervision of the Yemeni Department of Antiquities and the Cultural Section of the German Foreign Ministry. The find hoard included 12,000 Quranic parchments, all of which were incomplete and only contain some folios. The restoration was completed in 1989.

Ursula Dreibholz served as the conservator for the project, completing the restoration of the documents and designing the permanent storage of the manuscripts. She also collated the many fragments that helped to identify the distinct Quranic manuscripts from the others.

The manuscripts are located in the House of Manuscripts in Yemen, and were published in 2012 and 2017.

What Does the Manuscript Say?

A radiocarbon analysis of the manuscript shows that the lower text was likely to have been written between the years of 578-669 AD. This could mean that it is one of the earliest versions of the Quran to have been written, as these dates place the text within the first century of Islam.

Both the upper and lower text is written in what has been identified as the Hijazi script. The Hijazi Script (also called Hejazi) is the collective name given to early Arabic scripts that developed on the Arabian Peninsula, including at the sites of Mecca and Medina. This was a script that was used in the founding years of Islam.

The upper text appears to have been a complete text of the Quran, but it does not seem to be the case for the lower text. In a standard Quran, the chapters follow a sequence of decreasing length. The manuscript that has been discovered, however, is not complete and as such, it has been difficult to determine if the Quran follows the same pattern.

The upper text does conform closely with the modern Quran, and it has been dated between the 7th and 8th centuries. The writing of the manuscript is densely packed from page to page, but with a wide range of spacings: the text transcribed on each page varies from 18.5 to 37 lines. Much of the decoration of the pages remains unfinished though it does include individual verse separators.

The Lower Text

The lower text is believed to have been written between 632-669 AD as the parchment has been radiocarbon dated to 95% accuracy before 669 AD. However, there is a 75% probability that it was made before 646 AD.

This would place its composition within a couple of decades of the death of the Prophet Muhammed. Nothing from the Bible has this level of contemporaneity with regards to Moses, or Jesus.

What remains of the lower text has been identified through the metals used in the ink. By utilizing ultraviolet light, the conservators have been able to read some of the original text. It also appears in light brown on some of the parchments.

Parchment was durable and expensive and so it was common to practice to scrape original text away from the parchment and reuse it. This was either done because of damage or disused text, but was not common for Qurans, and the Sanaa cache is one of the only examples of an original Quran being reused for a later edition.

Uthman, the companion of the Prophet, is known to have standardized the text of the Quran around 650 AD, at which point the wording became crystallized and inviolable. If this is the case the lower text is heresy indeed, as it represents material evidence of human composition of the Quran, something which would be impossible if the text is the literal Word of God.

There is an intriguing alternative suggestion however.

Bismillah

The Quran is divided into 114 chapters, called “Surah”. All but one of these chapters, Sura 9, starts with the word “Bismillah”, meaning “In the name of God, the Most Gracious, the Most Merciful”.

However, Surah 9 in the lower text of the Sanaa Manuscript does contain this word, with an intriguing addendum not found in the standard Quran. The text which immediately follows states “Do not say ‘In the name of God’”.

A couple of reasons have been suggested for this non-standard inclusion. The first is that “Bismillah” should appear at the start of each of the Surah but that in this instance it should not be spoken aloud. This would explain its absence in the standard Quran, where it is to be thought but not read.

Could this therefore be an instruction on reading the Quran aloud, with the new insertion understood as a side note on how to speak the text? This would align the lower text with later Quran manuscripts.

Or could the lower text be a record from memory, imperfect because of the author’s imperfect recollection? Before 650 AD the Quran was passed on orally, which could allow these errors to creep into the texts. Further, some individual readings in the lower text appear to have been corrected in a separate hand to better comply with the standard Quran, which would fit with this hypothesis.

Why is it important?

Two things make the Sanaa manuscript massively important. The first is its dating: it may be one of the earliest manuscripts of the Quran and can show how the document developed both before and after the standardization of the Quran by Uthman in the middle of the 7th century.

The second is the differing text. Researchers have concluded that the original manuscript is much more likely to be before the standardization because of the variations in the text and the size of the document. It would have taken the skin of more than 200 animals to produce and as such, it is likely that rather than throwing away the document, the manuscript would have been cleaned and reused.

The early origin of both layers of text and its fine physical condition means that these manuscripts are incredibly important for the understanding of the history of Islam. While the differences in the text remain unexplained, comparison with the standard Quran offers a unique insight into those who wrote it down for the very first time, almost 1,400 years ago.

Top Image: The Quran today exists in one form only. Source: Дмитрий Громов / Adobe Stock.

By Kurt Readman