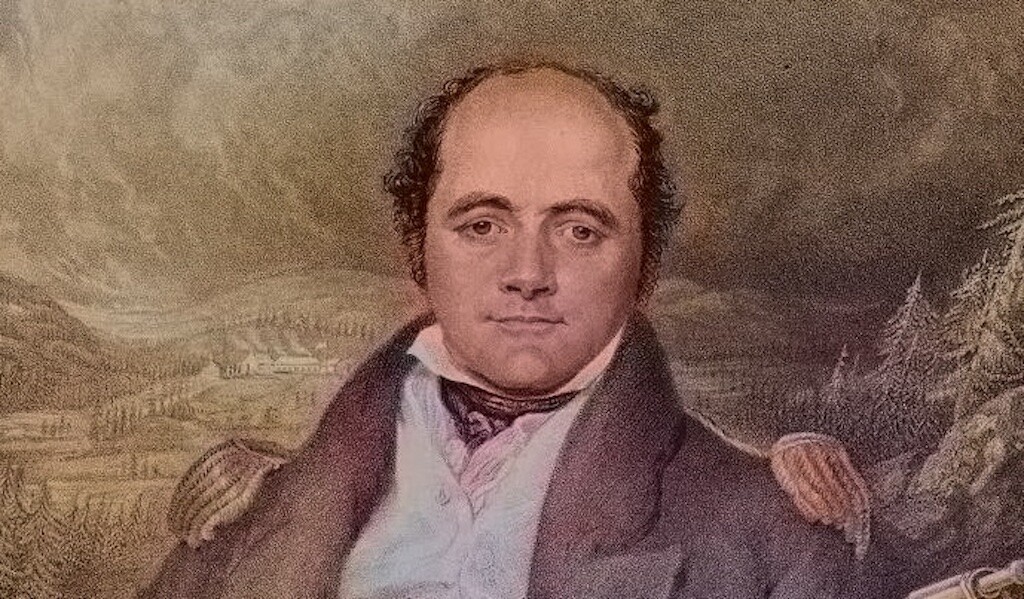

The quest for the Northwest Passage between the Atlantic Ocean and the Pacific Ocean was of great interest to Victorian Britain, whose maritime vessels sailed the world in support of its colonies and trade. Once found, the fabled passage would reduce the distance between Europe and the Far East dramatically. In 1845, Sir John Franklin was one of the brave explorers to accept the treacherous challenge to find this elusive route. But the doomed Franklin expedition met with great tragedy in the Canadian Arctic and ushered in a mystery that would last many decades. Over the course of 170 years, the details of a story filled with bravery, deep loss, and rediscovery have come to light.

The Franklin Expedition Sets Sail

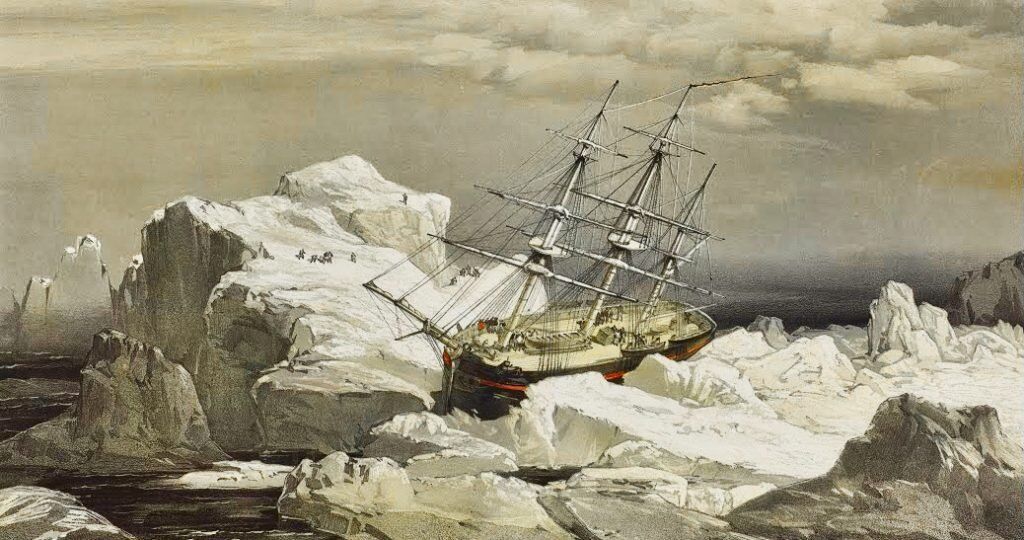

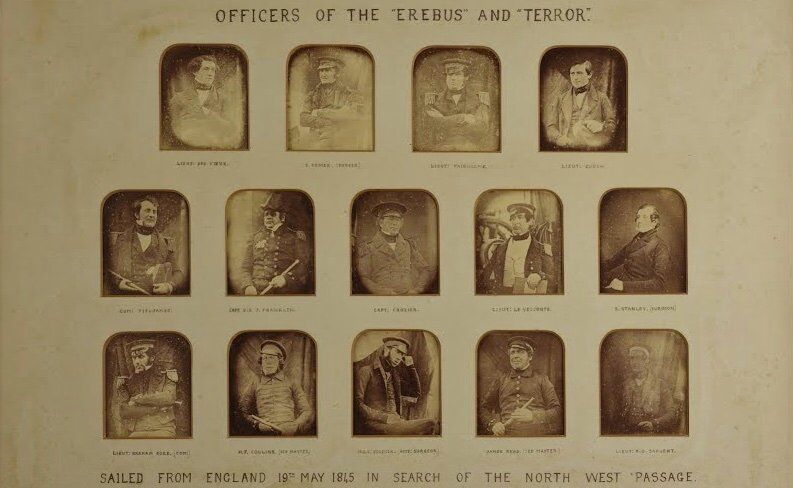

On May 19, 1845, Sir John Franklin and his crew of 128 people boarded two ships, the HMS Erebus and the HMS Terror. Their sole mission was to discover the Northwest Passage. Engineers reinforced the ships to manage this journey in rough Arctic waters. Other laborers stocked the vessels with three years worth of supplies, including canned food and a large library that included the works of Charles Dickens.

With high hopes, the crews set sail and journeyed north. In early July, the crew sent their last letters home from Whale Fish Islands near Greenland. Sir John’s letter to his wife, Lady Franklin, asked her not to worry if they didn’t return in time, as they might have to pass an additional winter on the ice. A European whaling ship in the Baffin Bay last saw the ships of the Franklin expedition on July 26, 1845. Then the expedition fell silent.

Sir John Franklin and His Crew Fail to Return

Later discoveries revealed that Franklin and his crewmen spent the winter of 1845-1846 camped on Beechey Island in the Canadian Arctic Archipelago of Nunavut. Once the ice broke in the spring, they sailed to the northwestern portion of King William Island. Sea ice trapped them at Victoria Strait and refused to let them go. In 1847, after two years with no word from anyone in the expedition, Lady Jane Franklin and others back in Britain began to fear the worst.

[blockquote align=”none” author=”Neil Bettridge”]Lady Jane was a wealthy and influential woman who began petitioning the Admiral to send search parties. She campaigned vociferously and successfully for the Admiralty to send out ships to look for Franklin, his crews and their ships, which they did, albeit somewhat begrudgingly at times. She was also prepared to put up money herself to fund expeditions of her own (4 of them between 1850 and 1853) and got a wealthy American, Henry Grinnell, to fund another one as well.[/blockquote]

Desperate for any leads, in 1850 the British government put out rewards. They offered £20,000 to anyone who might find the ships and £10,000 for any information. Lady Franklin also put out a reward of up to £3,000 to any whaling ships that went outside of their normal routes to search for the expedition. She even lobbied foreign governments for aid and hired a clairvoyant who incorrectly indicated that Franklin was still alive and trying to find his way out of the ice.

In Search of Franklin’s Lost Expedition

The first confirmation of the missing crew came in 1850 when the Captain of the HMS Resolute found the graves of three of the men at Beechey Island, Nunavut. This was where Franklin’s expedition spent its initial winter.

Then in 1854, Dr. John Rae embarked on a search for Franklin’s lost expedition. Rae was a surgeon from the Orkney Islands of Scotland. He worked for the Hudson’s Bay Company in Ontario treating both indigenous and European employees. As an avid outdoorsman, he was very familiar with the immediate Arctic area, and he set off under the authority of the British Admiralty and the Hudson’s Bay Company.

Rae had experience with the Inuit culture, and his interpreter could manage a decent amount of communication with them. After he offered rewards for any information regarding the lost men, the Inuit told him second-hand accounts of tribal members who had encountered groups of “white” men heading in a southerly direction in 1850. The following spring they saw about 30 bodies that had perished during the winter. Some of the corpses lay frozen in tents or under an overturned boat used as a shelter, while still others were scattered in various directions. They also learned that three bodies turned up near a river on King William Island.

[blockquote align=”none” author=”Dr. John Rae”]From the mutilated state of many of the corpses and the contents of the kettles, it is evident that our wretched countrymen had been driven to the last resource — cannibalism — as a means of prolonging existence.[/blockquote]

At the end of his investigation, Rae returned with a number of items from the ships and personal belongings of the crew members that he purchased from the Inuit. Included was a medal that belonged to Sir John Franklin.

You May Also Like: Cannibalism in the Donner Party

The 1859 Search Turns Up More Clues

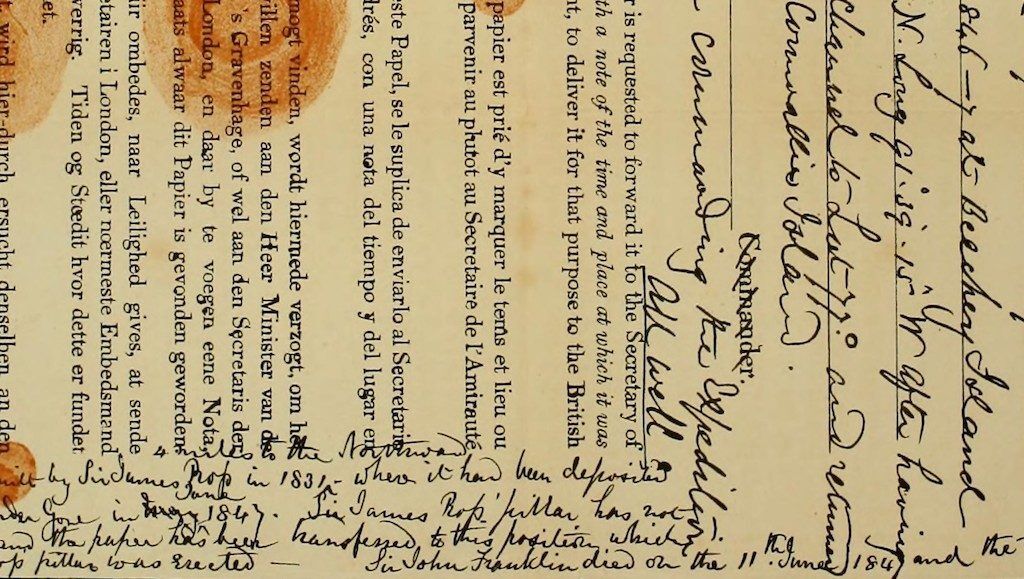

In 1859, Lady Jane Franklin hired Leopold McClintock to search for information about her husband. His investigation confirmed that Sir John Franklin was indeed dead. When McClintock went to King William Island, his crew found the Victory Point note. One entry dated May 28, 1847, provided details from 1845 that outlined the ship’s early movements. The words “All Well” in the letter indicated a scenario that would not last.

The second entry dated April 25, 1848, detailed how things had turned for the worse. Nine officers and 15 men perished, and the remaining men abandoned the ships on April 22. Sir John Franklin had died on June 11, 1847. The rest of the crew members were making their way to Back’s Fishing River, which was 746 miles south.

McClintock followed a trail of scattered corpses. He found two men who had perished in a boat, a sled made of ship wood that carried silver teaspoons, slippers, the book The Vicar of Wakefield, and unopened tin cans of meat. It was a mystery as to why these things would seem so important to carry. Also, why didn’t they open the cans of meat if they were starving? Were these things to barter with in case they ran into the Inuit?

You May Also Like: Abandoned Lifeboat on Bouvet Island: Mystery Solved!

Further interviews with Inuits indicated that ice destroyed one of the vessels, but the other eventually sank upright further south.

Discovery of the HMS Erebus and HMS Terror

Although many people endeavored to find the Erebus and Terror, it took 170 years to locate their remains beneath the frozen waters of Northern Canada. In the autumn of 2014, a crew from Parks Canada relied on local lore from the native population and various suggestions to find a ship on the ocean floor in an area where Franklin’s crews were thought to have gone. They found the heavily damaged wreckage of the Erebus in shallow waters. The team retrieved the ship’s bell and planned to explore further to determine the condition of the Erebus and its contents.

Two years later, in 2016, a native Inuit hunter told researchers of a tall wooden pole that he had seen sticking out of the sea several years prior, south of King William Island. When they went to the spot, they did not locate the pole, however, with further exploration, they soon uncovered the remains of the Terror at a depth of about 75 feet of water. They were pleased to discover that the wreck was in much better shape than the Erebus had been. A spokesman from Parks Canada told Global News that the ship still contained “overturned armchairs, thermometers on the wall, stacked plates, chamberpots…an incredible array of artifacts.”

Ownership Rights and Further Research

After the discovery, questions arose about the ownership of the sunken ships and their artifacts. In October 2017, the British government declared that it would keep a small number of artifacts, while the ships themselves and the rest of the artifacts on board would belong to Canada and the local native population.

You May Also Like: SS Baychimo: Ghost Ship of the Arctic

While the recovery and study of Franklin’s ships continue, the fate of most of the crew members remains a mystery. Presumably, they perished before they could reach civilization. Only roughly 25 bodies were recovered, and, surprisingly, four of those showed female DNA. This either means there were errors due to the age of the DNA, or females impersonated male sailors to get on board — something that was surprisingly common. (Daley, 2017).

A Tragic Story Lives On

The story of Franklin’s expedition and its ships live on in popular literature. None other than Jules Verne mentioned the ships in his classic Twenty Thousand Leagues Under the Sea. Joseph Conrad references the expedition in his Heart of Darkness. The story is a key plot point in Clive Cussler’s novel Arctic Drift. Additionally, the comedian/actor/author Michael Palin wrote a well-known book, “Erebus: the Story of a Ship.”

Twenty-three separate expeditions took place in search of the lost crew and ships. This testifies to the high regard and deep respect for the officers and crew of the Franklin expedition and the burning desire of so many people to find them. Although everyone in Franklin’s fateful expedition presumably succumbed to the hostile Arctic environment, their loss was not in vain. It was during his 1854 search that Dr. John Rae found the Northwest Passage that, 52 years later in 1906, Norwegian Roald Amundsen would successfully complete.

Updated by HM editorial staff on November 7, 2019.

References:

Bettridge, Neil. “Lady Jane Franklin; an International Woman.” Derbyshire Record Office, March 20, 2019.

Daley, Jason. “DNA Could Identify the Sailors (Including Women) of the Doomed Franklin Expedition.” Smithsonian.com. Smithsonian Institution, April 26, 2017.

Google Arts and Culture. “The Last Voyage of Sir John Franklin.” Derbyshire Record Office.

Potter, Russell A. “The Fate of Franklin.” Sir John Franklin.

Smith, Roff. “Arctic Shipwreck ‘Frozen in Time’ Astounds Archaeologists.” National Geographic, August 28, 2019.

Weber, Bob. “Photos: First Look at HMS Terror Shows Boat from Doomed Franklin Expedition Intact.” Global News, August 28, 2019.