Throughout World War II Nazi Germany was a crucible of advanced and experimental aviation technology. Leaving no stone unturned in their search for aerial dominance, the Nazis developed numerous unconventional aircraft designs during this period. Of them all the Lippisch P-planes stand out as some of the most bold and ambitious. Their creator, Alexander Lippisch, sought to revolutionize aerial combat by using ramjet technology and a new fuel source. If they worked, these planes promised unprecedented speeds and performance, but it was a big if. With the Allies in the skies above and their troops knocking on Germany’s front door, Lippisch found himself in a race against time to prove his designs could save the day.

Lippisch’s P-Planes- Crazy Enough To Work? Lippisch’s Vision

As a visionary aeronautical engineer, Alexander Lippisch was the kind of man who liked to think outside the box. He spent most of WW2 working for the Nazis on various plane designs and as the war dragged on, his designs tended to become increasingly ambitious.

In 1942, he was working on the Messerschmitt Me 163 for the Nazis, a rocket-powered interceptor aircraft that would go on to be the world’s only ever rocket-powered fighter aircraft and the first piloted craft to exceed 1,000 km per hour (620 mph), when inspiration struck.

He came up with the idea of a plane with a sharply swept, leaf-shaped delta wing which, he believed, could fly at supersonic speeds. He worked on the idea through 1943 and 1944, building upon it until it evolved into the idea of a hollow delta wing with an interior designed to act as a ramjet. Rather than a frame with engines attached, Lippisch had designed an engine with a plane built around it in the shape of one big wing.

Central to this design was the ramjet itself. A ramjet is a type of jet engine that doesn’t have moving parts. Unlike traditional turbojets, they rely on the aircraft’s speed, rather than fans (which can fail) to compress incoming air. This air is then mixed with fuel and ignited, producing thrust.

Ramjets are most efficient at high speeds, typically above Mach 2, making them suitable for supersonic flight. Lippisch’s interest in ramjets stemmed from their potential to propel aircraft to speeds far beyond the capabilities of conventional propeller-driven planes. He envisioned aircraft that could outrun and outmaneuver any enemy, providing a significant tactical advantage.

What Lippisch had come up with, if his math was right, had the potential to be the ultimate interceptor, capable of turning the tide in WW2’s aerial battles. Except Lippisch’s design had an interesting caveat- it carried no weapons. Instead, it would be heavily reinforced and designed to ram into opponents at supersonic speeds. Unconventional, to say the least.

With such a purpose, the plane was initially designed to be 100% disposable, with the intention of the pilot bailing out at the end of the mission. Presumably, at some point someone pointed out how incredibly cost-effective this would be, so Lippisch added a landing skid to the early designs. To get the plane to speeds where its ramjet could kick in, either a catapult or booster rocket could be used.

From Idea To Realization: The P.12 and P.13a

In August 1944, Lippisch moved to the Aviation Research Institute Vienna in Wiener Neustadt so he could work full-time on his new design alongside his partner, Messerschmitt mathematician Hermann Behbohm (who split his time between projects). While there, Lippisch worked on two designs in tandem, the P.12 and P.13a.

The P.12 was the slightly more traditional of the two designs. Rather than being a single project, the P.12 was more like a collection of designs that were workshopped and, if they worked, added to the P.13a. During the project, Lippisch kept butting heads with the famed German aircraft designer Willy Messerschmitt about the design of the P-Planes. The P.12 seems to have been Lippisch’s way of distracting Willy by letting him add his ideas to a plane he had already lost interest in.

The P.13a was the design that Lippisch genuinely cared about and was the far more ambitious of the two. By 1944, he had become convinced that solid fuel was a better power source for short-duration high-speed flights compared to traditional liquid fuels. His argument was that it was easier to precisely control the location of combustion compared to a liquid. Normally this would have been a hard sell, but by late 1944 conventional liquid fuels were hard to get, making a coal-powered interceptor sound incredibly tempting.

Much like the P.12, the P.13a went through a lot of design revisions. While most of these were technical changes to the aerodynamics we won’t obsess over here, others were much bigger. In particular, a version designed to carry gun armaments was wind tunnel tested, suggesting Lippisch was rethinking his original kamikaze design choice.

The propulsion system also went through several iterations. Lippisch’s original design, which used brown coal pellets to produce carbon monoxide gas, which was then mixed and combusted with air, proved to be inefficient. This led to other fuel sources like bituminous coal and pine wood heat-soaked in oil or paraffin being considered instead.

Despite these problems, the P.13a finally reached a point where full-scale aerodynamic trials could be carried out in 1944. Lippisch had a glider made to the same specifications as the P.13a, called the DM-1. While this was being built, however, Lippisch grew bored with the project and handed it over to students from the Darmstadt and Munich Universities to play with. Lippisch had moved on to the P.13b, yet another revision.

Losing the War

Unfortunately for Lippisch, his constant tinkering with the P-Plane designs meant none of them were ever finished. The DM-1 was captured by the Americans during Germany’s fall at the end of the war. They forced what was left of Lippisch’s team to finish the glider and then shipped it back home for trials.

The P.13b, on the other hand, was just going through its first tests when the Russians marched into Vienna. Lippisch was forced to flee and leave his latest baby behind. He escaped the Russians and was taken in by Operation Paperclip, which sent him to work at the White Sands Missile Range in New Mexico.

Were The Designs Viable?

The theoretical performance of the Lippisch P-planes was impressive. Ramjets offered the potential for sustained supersonic flight, which could have made the P.13a a formidable interceptor. The delta wing design provided stability at high speeds and the potential for rapid, agile maneuvers.

However, several significant challenges remained unresolved. The coal-fueled ramjet was an unproven technology. Igniting coal at the high speeds necessary for ramjet operation posed serious technical hurdles. Additionally, the lack of advanced materials and manufacturing techniques in wartime Germany meant that building an airframe capable of withstanding the stresses of supersonic flight was a formidable challenge.

Ignoring these problems, there was also the fact that Lippisch had come up with a flying battering ram. Shooting a moving target is hard enough, ramming into an enemy plane at 1000 km an hour would have taken a tremendous amount of piloting skill and bravery. Building a plane that could survive that impact was next to impossible, making the P-planes a single-use proposition. A hard sell during a war that had already severely drained Germany’s resources.

Even if these technical challenges had been overcome, the strategic impact of the P.13a is debatable. By 1944, the Allies had established air superiority over Europe. While the P.13a could have potentially disrupted Allied bombing raids, it is unlikely that it could have reversed the overall course of the war.

Conclusion

Lippisch’s P-Planes may have had design problems, and the usefulness of a literal ramjet may have been dubious at best, but Lippisch was on to something. After forcing his team to finish the DM-1 and carry out testing, the Americans deemed the design to have merit. Elements of the P-planes were incorporated into NASA designs for many years to come. The delta wing design went on to inspire multiple aircraft, including the Dassault Mirage and Saab 35 Draken.

The Lippisch P-planes represent a fascinating “what if” in the history of aviation. Conceived at a time of desperate innovation, these aircraft highlighted the potential of ramjet technology and advanced aerodynamics. While they were never realized in combat, the P-planes highlighted the visionary thinking of Alexander Lippisch. The idea of a battering ram aircraft may sound crazy, but that’s what we use drones and some missiles for today.

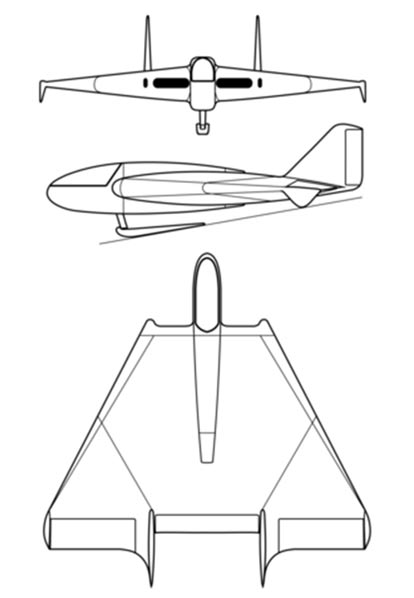

Top image: Model Photo of Lippisch planes, DM1 and P13a. Source: JuergenKlueser/CC BY-SA 3.0