It might sound like a cliche but sometimes your greatest allies can become your greatest enemies. That’s what happened to Thomas Becket, the Archbishop of Canterbury in 12th century England.

He went from being King Henry II’s greatest ally to someone the king just wanted to get rid of, their feud came to a grizzly end when Becket was murdered. Ever since, historians have been trying to work out if the Archbishop was killed on Henry’s orders, or if his murder was down to a misunderstanding.

The king’s true intentions are still debated to this day. Nevertheless, Becket’s demise sparked outrage and his subsequent martyrdom elevated him to sainthood.

A Royal Pain in the Archbishop

Becket was born in 1119 in London and was the son of Gilbert Becket and his wife, Matilda. Thomas’s father was most likely either a minor landowner or a petty knight from Thierville in Normandy. It’s believed Gilbert started out as a landowner but that by the time Thomas came along, he was living in London as a property owner, living off his income as a landlord.

Becket would have had a rather pleasant childhood. He was often invited to his father’s friend’s wealthy estates, where he was taught hunting and hawking. He was well-educated and was taught trivium and quadrivium at a grammar school in London.

At 20 Thomas traveled to Paris but shortly afterward his father lost much of the family fortune and Thomas was forced to begin working as a clerk. He later left this position to work for Theobald of Bec, the Archbishop of Canterbury.

This is when Thomas began making a name for himself. Theobald repeatedly sent him to Rome, Bologna, and Exerre, where he studied canon law.

In 1154 Thomas was promoted to Archdeacon of Canterbury and was given several important ecclesiastical offices by his benefactor. His big break came in 1155 when, on the advice of Theobald, King Henry II appointed Thomas Lord Chancellor, traditionally England’s highest-ranking minister.

As Lord Chancellor Thomas worked closely with the king and it was his job to milk the landowners, churches, and bishoprics for the king’s sources of revenue. The king was pleased with his work and even sent his son Henry to live in Becket’s household.

A Souring of Relations

So, what went wrong? Well, Beckett was made Archbishop of Canterbury in 1162, several months after Theobald’s death. Theobald had been a political creature, putting his loyalty to the king and government over his loyalty to the church he presided over. It was hoped that, as Theobald’s disciple, Thomas would do the same.

But it was around this time that Thomas became an ascetic, someone who abstains from sensual pleasures to pursue their spiritual goals. Simply put, Thomas began taking his religion very seriously.

A rift between Henry II and Thomas began to grow after Becket resigned his chancellorship and started trying to extend the rights of the church. There were several fallings out between Thomas and the king, including one in which Thomas tried to diminish the jurisdiction that secular courts held over English clergymen.

Seeing Thomas as a growing threat, Henry began trying to turn the other Bishops against him. This led to Henry hosting the Constitutions of Clarendon, a final attempt by Henry to make Thomas toe the line.

On 30 January 1164, Henry II held assemblies with most of England’s higher clergy at Clarendon Palace. He asked them all to sign documents that gave the church less clerical independence and weakened Rome’s sway over the church in England. The king was convincing and all but Becket refused to sign.

As a result, Becket was summoned to Northampton Castle on 8 October 1164. He was accused of “contempt of royal authority” (essentially being a nuisance) and malfeasance (not doing his job properly) during his time as Chancellor.

Unsurprisingly, Beckett was convicted. Before he could be sentenced, however, he stormed out and fled to Europe. Henry was furious and went after Thomas and anyone who dared to support him with a series of edicts.

King Louis VII of France, happy to get one over on Henry, offered Thomas his protection. He spent the next two years hiding in the Cistercian abbey of Pontigny.

While there he lashed out at Henry by threatening him and the English bishops with excommunication. Unfortunately for Becket, the Pope, although sympathetic, wasn’t looking to make an enemy of Henry II and went for a more diplomatic approach.

In 1170 Pope Alexander III sent several delegates to England to look for a compromise. It worked and Thomas was allowed to return from exile soon after. The peace was short-lived.

“Will No-one Rid Me of this Turbulent Priest”

The straw that broke the camel’s back came in the June of 1170 when Henry II asked Roger de Pont L’Évêque, Archbishop of York, Gilbert Foliot, Bishop of London, and Josceline de Bohon, Bishop of Salisbury to come to York and crown his son, Henry the Young King. This was a role usually reserved for the Archbishop of Canterbury and in November 1170 Becket responded to this slap in the face by excommunicating all three.

- Sir Francis Walsingham: Who was Queen Elizabeth’s Spymaster in Chief?

- Elizabeth Barton: The Nun who stood up to Henry VIII

What happened next is up for debate, but most historians agree that Henry II was less than pleased. He is most often quoted as having said, “Will no-one rid me of this turbulent priest?”, but in truth this is an anachronism, a much later quote from 1740.

The sentiment seems to be there , however. A more likely quote comes from his contemporary biographer, Edward Grim, who wrote, “What miserable drones and traitors have I nourished and brought up in my household, who let their lord be treated with such shameful contempt by a low-born cleric?”

Whatever Henry said, his knights took it as a call to action rather than as a rhetorical question. Four of his top men, Reginald FitzUrse, Hugh de Morville, William de Tracy, and Richard le Breton raced to Canterbury to confront the problematic Archbishop.

According to eyewitness accounts, they arrived armed and armored on 29 December 1170. They left their weapons outside the city Cathedral, but entered still wearing their armor hidden beneath their cloaks.

They told Becket he was to come with them to Winchester to answer for his actions. When Becket refused, they went outside and gathered their weapons. Upon their return, one of the knights shouted, “Where is Thomas Becket, traitor to the King and country?”

Becket reportedly responded by saying, “I am no traitor, and I am ready to die.” When one of the knights tried to pull him outside, Becket resisted by holding onto a pillar. From there, things rapidly escalated and Becket ended up dead.

It was an absolute mess in the moment, and what followed only worsened the situation for Henry. In death Becket became a martyr and less than two years later was canonized by Pope Alexander III. The same year his sister, Mary, was made the mother superior of Barking convent as reparations for her brother’s murder.

On 12 July 1174, Henry traveled to Becket’s tomb, which had become a popular pilgrimage site, to humble himself in public penance. While he never went as far as having the four knights arrested, he also did nothing to help them.

They spent a year in hiding before being excommunicated by the Pope. They ended up traveling to Rome to seek forgiveness and were ordered to serve as knights in the Holy Lands for the next 14 years.

Did Henry really want Becket dead, or was his death just a tragic mistake? We don’t know for sure. But it’s clear that his rhetoric and anger towards Becket created an atmosphere where his words were interpreted as a call to arms. Henry ultimately came to regret his words and he and his knights paid a heavy price for them. A lesson some modern leaders would do well to keep in mind.

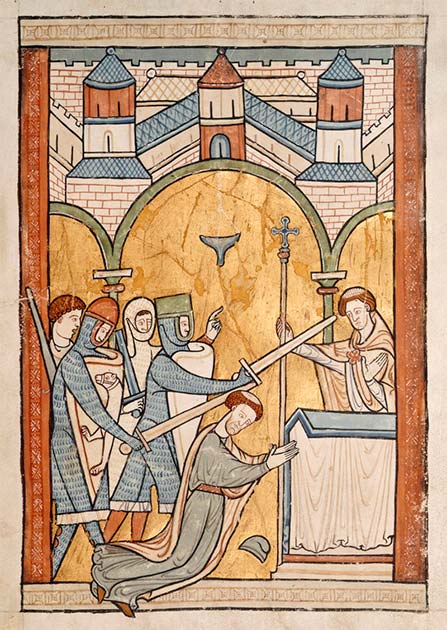

Top Image: Knights from Henry II’s court kill Thomas Becket in Canterbury Cathedral, striking at his head with their weapons. Source: Meister Francke / Public Domain.