In the late 1900s, the British worked to build a railroad from Uganda to the Indian Ocean at Kilindini Harbour in Kenya. In March of 1898, a crew was working on constructing a railroad bridge over the Tsavo River in Kenya.

The bridge was to span eight miles (13km), and several camps of workers were spread across the area. Two days before the project’s leader, Lieutenant-Colonel John Henry Patterson, arrived in Tsavo, workers began disappearing.

Over nine months, two apex predators stalked, dragged, and ate construction workers at night while asleep. This is the story of the Tsavo Maneaters, and how humans are not at always the top of the food chain as we like to believe.

The Terror of Tsavo

The Tsavo Maneaters were a pair of man-eating, mane-less lions who terrorized the crew building the bridge over the Tsavo River in Kenya. While most male lions are seen with manes, not all males will have them.

This might be due to polymorphism, which in biology is the occurrence of two or more visibly different forms of phenotypes in a population of a species of animals. Unlike most lions in Africa, “Tsavo male lions generally do not have a mane, though coloration and thickness will vary. There are several hypotheses as to why this occurs.”

One idea is that mane development is closely related to climate as manes can help reduce heat loss at night, but during the scorching days in the desert, it can lead to dehydration and excessive panting. Another reason the Tsavo lions lack manes might be an adaptation to the thick, thorny vegetation in the Tsavo region, which would interfere with a lion’s hunting abilities.

Once Lieutenant-Colonel John Henry Patterson arrived at the building site, he and his crew went to bed at night, fearing they would be taken as prey before the sun would rise the next day. At one point, the attacks seemed to stop; however, this was not the case.

- The Beast of Gevaudan: Monstrous Wolf or Something Else?

- Wendigo: Cannibal Beast of Native American Legend

The Tsavo Maneaters simply moved to other camps and ate workers there. The Maneaters returned to the main camp, and their attacks became more intense and frequent. Men were being killed and devoured daily, and the crews tried to keep the pair of lions away however they could.

The workers would build large fires, hoping the smoke and flames would keep the lions out, but when this failed to stop the Tsavo Maneaters, they tried another method. The men built thorn fences known as bomas from the branches of the whistling thorn trees that surrounded their camp. This also failed to slow down the Maneaters; the lions would jump over or crawl under the thorny fences to feed.

Most of what we know about the Tsavo Maneaters came from letters from workers and John Henry Patterson’s semi-biography The Man-Eaters of Tsavo. According to Patterson’s writings, at first, only one lion would enter the camps and snatch a victim, but as time passed, both lions became bold enough and would enter the camps to feast together.

As the Tsavo Maneaters ate more and more men, hundreds of workers fled the area, which caused the construction of the bridge to be put on hold. By this point, “colonial officials began to intervene” to get construction back on track. Patterson alleged that the District Officer, Mr. Whitehead, almost fell victim to the Maneaters shortly after reaching the Tsavo train depot in the evening. Sadly, Mr. Whitehead’s assistant, known only as Abdullah, was killed while Whitehead himself barely escaped, with significant claw scratches along his back.

The Hunt

The Tsavo Maneaters kept eating workers, and officials decided that the beasts should be hunted to protect the builders and get the construction back on track. Patterson was said to have set several traps and tried to surprise the Tsavo Maneaters by attacking them from a tree at night.

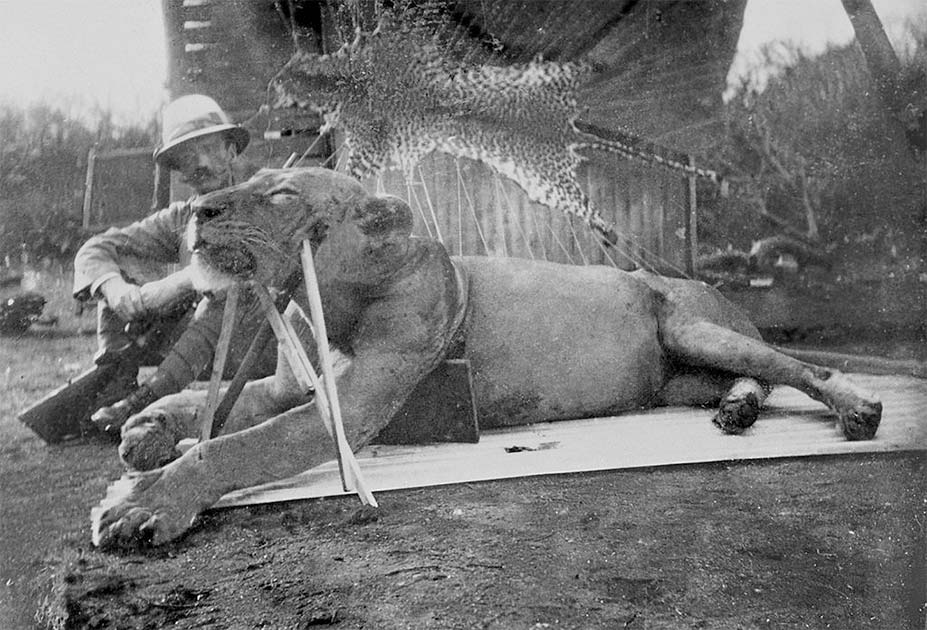

After countless failed efforts to kill the Tsavo Maneaters, Patterson was finally victorious and shot the first lion on December 9, 1898. The first Maneater was a perfect example of how large the Tsavo lions can be.

This lion was huge, measuring 9 ft 8 in (2.95m) from the tip of its nose to its tail. Eight men were needed to return the lion’s remains to the camp. According to Patterson’s book, the first Tsavo Maneater had been shot in the back leg earlier that day but escaped. Upon the lion’s return to the camp that evening, he was shot “through the shoulder, penetrating its heart.”

The second Tsavo Maneater was taken down with nine shots over several days. The first shot came from Patterson, who was perched on a scaffold he built near a goat also killed by the lion. Eleven days after the first shot, the lion was shot two more times but escaped.

The following day, Patterson shot the lion three times, which severely injured the beast but didn’t end its life. Patterson then shot it another three times, which finally killed the last Tsavo Maneater.

- Felines in the Moat? The Great Washing of the Lions Hoax

- Beware the Beast! Is there a Beast of Bodmin Moor?

The exact number of victims of the Tsavo Maneaters is questionable. Some sources claim that 35 people lost their lives, while others place the death count at 135 people.

Patterson gave different numbers of victims each time he spoke about it, which further puts some of his claims in his biography into question as well. All we can really confirm is that a pair of mane-less Tsavo lions killed and ate more than ten men who were working on the bridge construction over the Tsavo River.

What Triggered Man-Eating Behavior?

When it comes to human deaths caused by animals, lion attacks resulting in death are relatively low, averaging around 100 deaths per year. This may sound like a lot, but hippos kill about 500 humans per year, Ascaris roundworms kill about 2,700 people, with mosquitos taking the lead with around 830,000 fatalities a year due to transmission of illnesses like malaria, Japanese encephalitis, yellow fever, and dengue fever.

Unprovoked lion attacks where humans are eaten are relatively rare. Several scientists have studied man-eating behavior in lions and have suggested some of the following theories.

One theory was that it was due to an epizootic cattle plague (rinderpest) outbreak in Africa in 1989. The plague impacted the lion’s usual prey source, possibly forcing them to turn to humans as an alternative food source.

Another theory for why the Tsavo Maneaters ate men might have been due to the lions growing used to finding dead humans in the Tsavo River. Back at the time of the attacks, East African slave trading ships coming from Zanzibar had to cross the river, and the bodies of dead enslaved people would be discarded in the lion’s territory.

An often contested theory was that one of the lions had a damaged tooth that would hinder its ability to kill prey like usual. Patterson claimed he damaged the lion’s tooth with his gun; however, in 2017, Dr. Bruce Patterson (no relation to Colonel Patterson) found one of the lions had an infection in the base of its canine tooth, which would have made it hard for it to hunt. If you want to see the skulls of the Tsavo Maneaters, they were purchased by the Field Museum of Natural History in Chicago in 1924 and remain there to this day.

Top Image: It is believed that the Tsavo Maneaters developed their taste for human flesh from the slaves who were force marched through the area. Source: Sean Nel / Adobe Stock.

By Lauren Aguirre