Much of the knowledge of the ancients has been lost. Many of the most famous works of the time, from high theatre to complex mathematics, have not survived.

Sometimes, a text comes down to us in a single manuscript. Sometimes, an oral tradition guaranteed the preservation of a story held to be of particular importance. And sometimes we have a tradition of preservation itself, a conscious effort at some point in history to catalogue and remember the past.

So it was with the Vatican mythographers, three authors of Latin texts that detail the core ancient Greek and Roman myths. We do not know who the three authors were, but all of the texts were placed together in a single medieval manuscript and were published in 1831 by the Italian Cardinal Angelo Mai.

There are three works associated with it, split amongst the three mythographers. One was found in a manuscript held by the Vatican itself, whilst the others were found elsewhere, but all dealt with the same subject. However, there is still much to be learned from these manuscripts. Why were they written and how has it shaped our understanding of Greek Mythology?

Why Were They Written?

These handbooks detailing mythological stories were compiled in part as a teaching aid. The collection allowed the three Vatican Mythographers to facilitate the education of the classical poets by drawing all of the key stories and poets together.

The Mythographers hoped they would be able to make clear, through their own annotations, the Christian purposes of incredible figures, themes, and places that could be found in the likes of Ovid and Vergil. This is most clearly seen in the first and second mythographer’s narratives.

The texts of the second and the third mythographer are very allegoric which hints at their origins being linked to philosophic morals as well. The Gods, Goddesses, and heroes of these texts are all associated with virtues and vices. For example, Perseus’ slaying of the Gorgon comes with Minerva’s aid: allegorically, he can use the virtue of wisdom to combat the vice of fear.

Many different types of people benefitted from the work of the Vatican Mythographers. Philosophers, astronomers, poets, and artists alike found inspiration and motivation from these works. It is clear for example that Jean de Meung’s Roman de la Rose extensively used the mythographer’s work for his information.

Influence from the third mythographer can be seen in the works of Petrarch and Bersuire. It has been suggested that the third mythographer in particular had a significant formative impact for the Italian Renaissance, offering a narrative guide for the iconography of mythical characters.

There are lots of similarities that can be found amongst these works and yet all also remain unique. They were all written in different eras and as such differences in terms of style and delivery.

Who Were They Written By?

The first Vatican Mythographer’s work was preserved in a document which survived from the 12th century. It is divided into three uneven books and covers a total of 234 myths. There does not seem to be an order or narrative to these stories.

Some are grouped together by purpose or relating materials, for example the labors for Heracles are all gathered together. All of the stories are kept relatively brief and last no longer than thirty to forty lines each, with one exception: the Genealogy of the Gods which, as obviously an important document, lasts for 82 lines.

One thing that has been noted by scholars of the first mythographer is that his style is fairly bland. He does cite sources of classical origins but offers few quotes from the big names of the period like Vergil, Horace, or Ovid.

In terms of length, the Second Vatican Mythographer is much longer than that of the first. The text also attempts to group the myths slightly more systematically and with a tad more purpose than the first. The author gives more in terms of explanations and interpretations from his classical sources and also seems to have consulted more sources than his predecessor.

The Second Vatican Mythographer has yet to be pinned down in history, and the dates given by scholars have varied. Some have tried to associate the writings with the 4th-century writer Lactantius Placidus whilst others have chosen to go with Remigius of Auxerre from the 9th century.

Others claim that it would not have been written until the same time as the First Vatican Mythography whereas some scholars have even suggested that it was by an anonymous ecclesiastical woman, though this remains unsubstantiated. It is more likely, however, that this author worked later than the First.

- Narcissus Myth: Early Poets and the Ancient Story

- Oxyrhynchus Papyri: Historical Treasure in Ancient Egyptian Garbage

The Third Vatican Mythographer has been renowned among scholars as the most interesting of the three. This is often due to their excellent Latin style and the allegorical focus that he offers from the myths that he has chosen to include. The author has included various sources for each myth and even presents the ones that conflict with each other. Even better for scholars of this work, the author refers to his sources by names and quotes them regularly.

Interestingly, the Third Vatican Mythographer inserts within their work a sense of personality. The writer often comments on points and renders their own opinion. Often this can be seen in the admission of uncertainty about the validity of a source of confusion about what the story is trying to say.

Despite these hints, the author also remains anonymous. The surviving manuscripts teasingly refer to the author as Alberic of London who may be a 12th-century canon of Saint Paul’s. But we know almost nothing about Alberic either.

Who Did They Write For?

This is a question that literary historians of recent decades have discussed and debated. Whilst there is yet to be a definite answer, there are some well-evidenced theories. Mythographers undoubtedly had influence and reach across society.

However, during the Middle Ages, this was much more confined by widespread illiteracy and a religious culture that was hostile to anything “other”. By taking control of “Pagan Myths” Christian thinkers could present the greater authority of their views.

These books would begin to take the foundational study of those who were to become literary citizens of the Christian kingdom. By re-writing and translating the myths of the ancient world, Christians were able to not only teach the greats of the past but impose allegorical structure on them that would support their Christian worldview.

Pagan myths presented a threat to Christian authority and, due to the vast amounts of it, it could not be contained. By owning these stories and seeking to explain their meaning within a Christian context, the threat of paganism was defused.

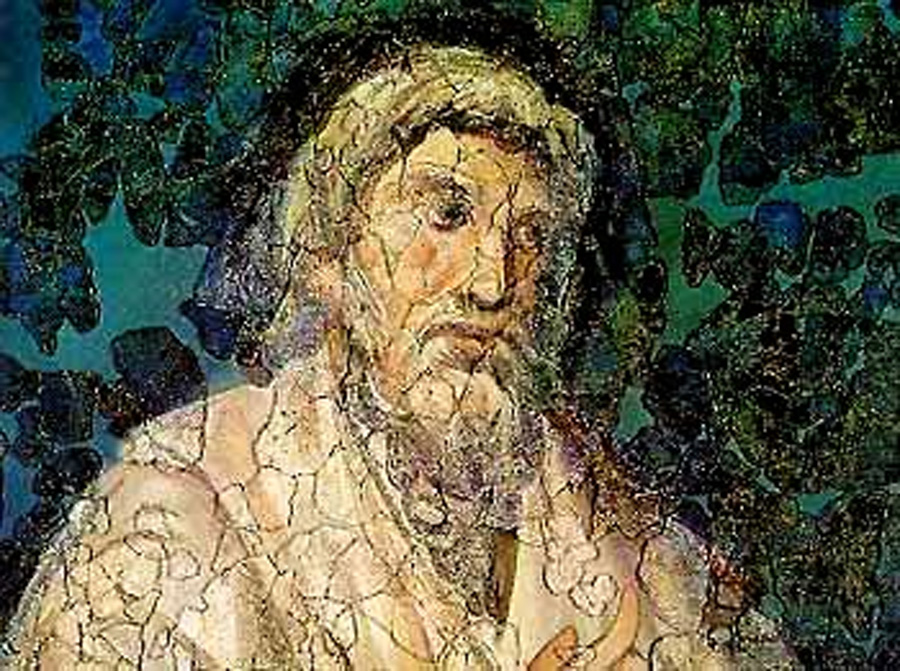

Top Image: What did Christian writers want with pagan mythology? Source: procinemastock / Adobe Stock .

By Kurt Readman