The Daguerreotype was the first publicly available photography form that became popular between the 1840s and 1850s. Named after its creator, Louis Daguerre, a daguerreotype was made by placing a mirror-finished polished sheet of silver-plated copper into a sensitized lighttight box with bromine and iodine vapors until the plate’s surface turned a yellow color.

The reaction between the iodine and the silver plating produced a light-sensitive iodide. Once the plate is sensitized, it is inserted into a camera, where exposure is used to capture an image. The daguerreotype is completed by placing the plate face down over the top of heated mercury dunes until the image develops on the plate. Being able to create photographs was a faster way to produce a portrait than sitting and painting a subject.

This meant that a photographer could create hundreds of portraits of a single subject which have now made their way into museum collections across the globe. One of the most significant figures in early photography besides Louis Daguerre was Virginia Oldoïni.

Hundreds of photos were taken of this enigmatic beauty which led to her being known as the Most Photographed Woman in History. Who was Virginia Oldoïni, and why was she so famous?

Virginia Oldoïni

Virginia Oldoïni was born Virginia Elisabetta Luisa Carlotta Antonietta Teresa Maria Oldoïni Rapallini on March 22, 1837, in Florence, Grand Duchy of Tuscany. Her parents, Marquis Filippo Oldoïni Rapallini and Isabella Lamporecchi, were members of the minor Tuscan nobility.

When she was 17 years old, she was married to a man 12 years older than she was, the Count of Castiglione, Francesco Verasis. Virginia Oldoïni was considered to be “the most beautiful woman of her day.”

She was said to have long, luscious wavy blond hair, a fair complexion, a soft and delicate oval face, and “eyes that constantly changed color from green to an extraordinary blue-violet” hue. While she was proud of her natural beauty, others saw her looks as a fantastic political tool.

During this period of history, an active effort was being made to officially establish an independent and unified Kingdom of Italy. Virginia Oldoïni’s cousin was Camillo, Count of Cavour, a minister of Victor Emmanuel II, King of Sardina.

- Marguerite Alibert: Courtesan, Murderess and Blackmailer of a King

- Incredible First Photographs and Milestone Images

The King of Sardinia also ruled over Piedmont, Val d’Aosta, Liguria, and Savoy. Her cousin learned that Virginia Oldoïni and her husband, the Count of Castiglione, were going to be traveling to Paris in 1855. The cousin told her she needed to meet Napoleon III to convince him to consider Italian unification. Virginia Oldoïni was told she needed to “succeed by whatever means you wish – but succeed!”

Not long after meeting with Napoleon III, Virginia Oldoïni became his mistress. She was a bright spot in the French court and became a popular figure in society.

However the affair with Napoleon III was very public, and as a result of the scandal, Camillo demanded to be “maritally separated” from Virginia Oldoïni. While they were still technically married under the law, Virginia Oldoïni was essentially cut off from her husband’s wealth and status.

After the separation, Virginia Oldoïni retreated to Italy in a sort of self-exile for several years in 1858. During her exile, she had a brief romantic affair with King Victor Emmanuel II of Italy.

Virginia Oldoïni finally returned to Paris and the limelight in 1861 and became a prominent member of Parisian society. Due to her affair with two significant royal figures, the social circles Virginia Oldoïni operated within expanded immensely.

She was introduced to individuals like Otto von Bismarck, the Duke of Lauenburg, Germany, Adolphe Thiers, the second President of France and first President of the French Third Republic, and Augusta of Saxe-Weimar-Eisenach, the Queen of Prussia and the first Empress of Germany as the wife of Wilhelm I, the first Emperor of Germany. Virginia Oldoïni also continued to have a string of prominent lovers, including (it was rumored) the then-director of the Louvre Museum.

The Pierson-Mayer Studio

Opened in 1844, the Pierson-Mayer photography studio was owned and operated by Pierre-Louis Pierson and the Mayer brothers, Louis-Frederic Mayer and Leopold-Ernest Mayer, which was the premier photography studio in Paris at the time.

The Pierson-Mayer studio specialized in daguerreotypes and retouching/inpainting portrait photographs with watercolor or oil paints. The Pierson-Mayer Studio became famous thanks to Emperor Napoleon III’s preference for their work after the Second Empire was established in 1852.

The photographers took portraits of the French nobility/imperial court, actresses, musicians, businessmen, members of the aristocracy, and even the kings of Sweden, Württemburg, and Portugal. Pierson was introduced to his finest muse, Virginia Oldoïni, in 1856.

- When Women Ruled the Papacy: Marozia and the Pornocracy

- Post Mortem Photography – Immortalizing the Dead

Virginia Oldoïni and Pierson got along so well that the pair would end up working together to produce hundreds of portraits across three distinct periods of Virginina’s life: her return to French society in 1856, her integration into life in Paris from 1861 to 1867, and once again towards the final years of her life from 1893 to 1895.

Some of the portraits the pair created were images that recreated moments from Virginia Oldoïni’s life that she considered significant to her. She was photographed in the finest of gowns or masquerade costumes at balls.

She would dress up as figures from the opera, literature, or her own unique characters. One of the earliest portraits of Virginia Oldoïni that we know of today is The Black Dress (now owned by the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York City), taken a few months after Virginia returned to Paris in 1856. Another well-known image of Virginia Oldoïni is of her wearing a Queen of Hearts-inspired costume dress, which was displayed in the collection of French works at the Exposition Universelle in Paris in 1867 (also known as the second world’s fair that was held in Paris).

Virginia Oldoïni was more than just a pretty model; she was incredibly interested in creating artwork and would often assume the role of art director in the shoots she posed for. She would create the idea or concept of the images and even would request that Pierson shoot her portrait from different camera angles.

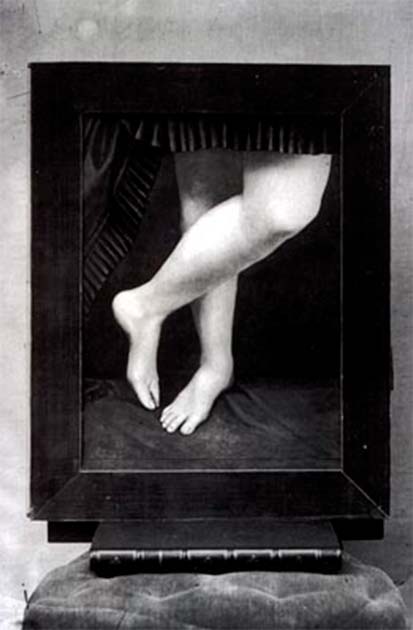

She would work with Pierson to determine which works should be enlarged or repainted. Repainting over the photographic images was done to add ornate details to an image, and she often was the one to do the repainting of her own photographs. Her repainted photographs have become the epitome of this unique genre of artwork. Virginia Oldoïni was known to send some of these portraits of herself in elaborate clothing or more scandalous images of just her exposed knees, ankles, and feet to her many lovers.

In the final years of her life, Virginia Oldoïni became a recluse. She seldom left her home, which she had redecorated in traditional funeral black with closed blinds and all mirrors shrouded with a cloth to hide her reflection.

She was distraught over her declining beauty and would only leave her home at night with veils on, which hid her face from those who might come across her. However she had one final project planned with Pierson and intended to create an exhibit of her photographs during the 1900 Exposition Universelles.

The photographs created during this period show that she was suffering from some kind of mental instability and are rather tragically beautiful. Unfortunately, her plans for an exhibit would never come to pass.

Virginia Oldoïni passed away on November 28, 1899, at the age of sixty-two. After her death, the art collector Robert de Montesquiou published a biography about Virginia Oldoïni, Countess of Castiglione, in 1913 called La Divine Comtesse. He also was able to amass a collection of 433 of the Countess’s photographs which he gave to the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York City. Several of her photographs can be found online at the Met’s online collection database for free.

Top Image: Virginia Oldoïni in 1863. Source: Pierre-Louis Pierson / Public Domain.