The Great Depression looms large in American history. The largest economic downturn in the 20th century sent out ripples across the US and the world, and as always with such financial crises it was the poorest who were hit hardest.

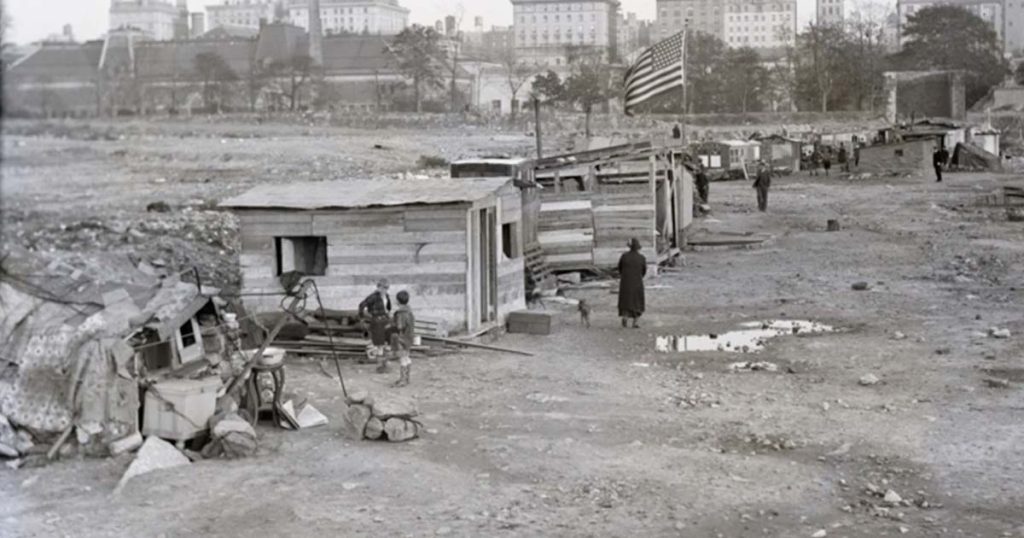

Unable to afford to sustain even a modest living and victimized, tricked and hoodwinked by predatory banks, many families were forced into living in homeless squalor. Entire shanty towns appeared, rife with disease and crime, and the public had no doubt in their minds as to who was to blame.

They called these towns “Hoovervilles”, deriving their name from the President of the United States, Herbert Hoover, who was in office at the beginning of the Depression. It was coined by Charles Michelson, an editor, and political publicist. Across the United States, hundreds of these Hoovervilles appeared in the 1930s.

One of the biggest and well-documented Hoovervilles was the one in Seattle, in Washington State, which stood for 10 years from 1931 to 1941. It encompassed nine acres (3.6 hectares) of public land and was the home of up to around 1,200 people.

During its existence, it created its own community government including an unofficial mayor. This community enjoyed the protection of leftwing groups and some public officials who were sympathetic to the cause. Unfortunately, this only lasted until the land was needed for facilities during the Second World War.

In order to understand these communities, it is important to get to grips with homelessness in the 20th century in America. How had the American Way failed these people so much?

Homelessness

With the economy crumbling in the early 1930s, homelessness began to spread across the United States of America. Many homeowners lost their property because they could not pay mortgages and taxes due to the lack of job opportunities at this time.

At the same time, renters were unable to pay their rent and many Americans found that they were living outside of the housing market. By 1932, homelessness had already reached the millions.

- The Battle of Blair Mountain: Unleashing the Workers’ Revolution

- London’s Notorious Female Gangsters: The 40 Elephants

Stories from victims of this crisis reveal that many people sought to squeeze in with relatives. Populations per home soared massively throughout the 1930s.

Many people squatted by avoiding eviction and staying in their property or moved into the many vacant properties that began to populate the country. But for hundreds and thousands of people this meant taking to the streets, finding shelter under bridges and on public land where they built shacks not dissimilar to those found in shanties around the world.

In some cities, squatter encampments were allowed but this did not last long. In any case, the scale of the disaster quickly overwhelmed any response these municipal organizations had prepared to fight it.

The shacks that arose in Seattle appeared as early as 1930 and 1931. The local authorities tried to prevent them and destroyed many of the shacks as they were built when the local community complained.

The main city’s Hooverville began as a small group of tiny huts on land found in Elliot Bay south of “skid road” (this was the colloquial term for Pioneer Square). The property that the shacks had been built on was owned by the Port of Seattle and had been occupied by Skinner and Eddy’s shipyard during the First World War.

The records reveal that the local police burned the early Hooverville site not once but twice. Each time the struggling population rebuilt them. In 1932, a new mayor took office, one who owed his support to the Unemployed Citizen’s League. The new mayor unsurprisingly took a much more lenient view of Hooverville.

The Population

By 1934, almost 500 self-built one-room shacks were scattered across the land with no real order or organization. Donald Roy, a sociology graduate who spent years studying the community, claimed that the buildings were “scattered over the terrain in insane disorder”.

639 residents in March 1934 and found that the majority of people living in these towns were men. Often, they were unemployed laborers and timber workers who had fallen out of employment and struggled to find a new job in throughout the 30s.

Despite mostly being one gender, the population was quite diverse in background. Most people were white and foreign-born. There was a particularly high number of Scandinavians. 29% of the population was made of non-white people such as Filipinos, African Americans, Native Americans, and Mexicans.

- Hovrinskaya Hospital: Russia’s Haunted Hospital of the Damned

- The Stoneman: A Serial Killer in 80s Calcutta?

Roy described the atmosphere as surprisingly quite relaxed, with the people thrown together making the most of the situation. Many of the men all socialized and intermingled despite their racial differences. A camaraderie had been developed through the terrible situation that they had found themselves in.

The local authorities attempted to regulate these sites by introducing modest sanitation and building rules. Children and women were not allowed to live in the Hooverville and the residents were expected to keep their own order.

This was done through an elected Vigilance Committee made up of six people drawn equally from the communities which made of the shanty town. It was led by Jesse Jackson, the unofficial “Mayor” of Hooverville. He wrote, in 1938 that the population in this area was fluid. Men sold their shacks to newcomers and moved on.

From the success here, other Hoovervilles were created. One was on the side of Beacon Hill, another in the Interbay area, and two more were built in South Seattle. The Health Department estimated that in 1935, approximately 4,000 to 5,000 people were living in shanty towns.

The End of Tolerance

Seattle city continued to support Hooverville until 1941. On the eve of joining World War II, the Seattle Health Department created the Shack Elimination Committee to try and identify unauthorized housing and to remove them.

A survey found that there were at least 1,687 shacks across five substantial Hoovervilles. By April, many of the residents of these shanty towns had been given notice to leave by May.

After this, the police covered the structures in kerosene and set them alight. Many spectators watched as the shanty town that had survived for 10 years in Seattle was burned to the ground in front of them.

This was not a unique case. As the nation began to turn its attention to the defense of democracy and the liberation of Europe, many of those who had been unemployed were able to find work in the army. This led to shelters and shanties closing and relief programs reducing.

Many of the Hoovervilles which were vacated were demolished systematically. Fortunately, after the war America recovered with its post-war boom. More people had jobs and the country was able to reduce homelessness. It would be another 30 years before it became a problem again.

Top Image: Seattle’s Hooverville on the tidal flats in 1933. Source: Seattle Municipal Archives / CC BY 2.0.

By Kurt Readman