Irena Stanislawa Sendler was a Polish social worker and humanitarian who served in World War II as a nurse in the Polish Underground Resistance. The Polish Underground Resistance operated in German-occupied Warsaw.

From October 1943 she was head of the children’s section of “Zegota”, the Polish Council to aid Jews. In the 30s, Sendler had worked as an activist connected to the Free Polish University.

From 1935 through to October 1943, Sendler worked for the department of Social Welfare and Public Health in Warsaw. Throughout her time here she rescued Jews, particularly women and children, out of the Ghetto in Warsaw. However, few today know who she is or what she went through.

Early Life

Irena Sendler was born in February 1910 in Warsaw. Her father was Stanislaw Henryk Krzyzanowski, a physician, and her mother Janina Karolina. However, she would grow up in Otwock, which was actually around 15 miles (24 km) southeast of Warsaw.

She was brought up in a strong Jewish community. Her father treated the poor, many of whom were Jews, despite them being unable to pay for his treatment. However, his charity may have killed him: he died in 1917 due to typhus likely contracted by one of his patients. After the death of her father, Sendler and her mother moved around Poland, first to Tarczyn and then Piotrkow Trybunalski.

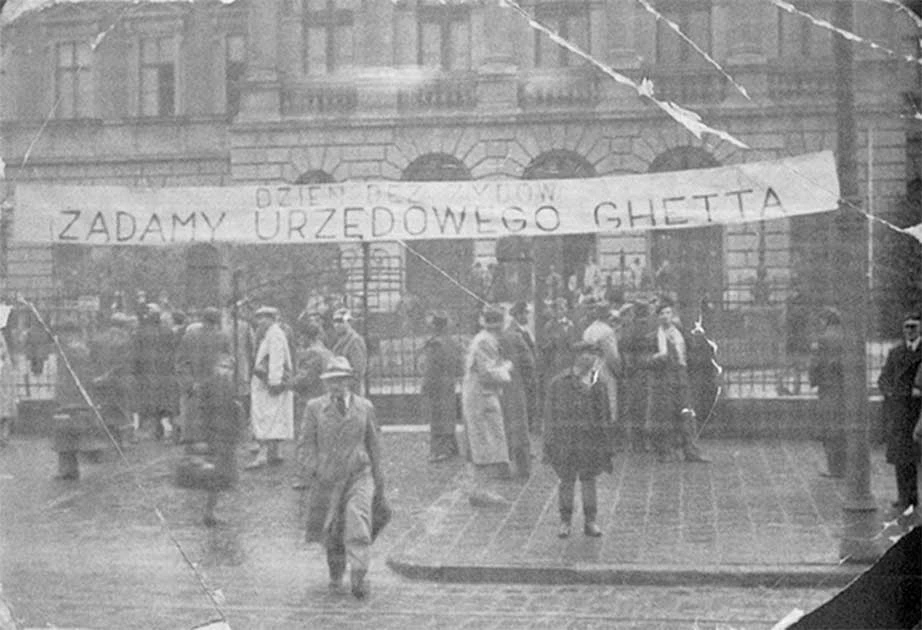

In 1927, at the age of 17, Sendler studied both law and Polish literature at the University of Warsaw. here she was exposed to the ghetto bench system that was being practiced at higher education institutions throughout Poland, something she came to strongly oppose.

This was a form of segregation in which Jewish students were required to sit on the left-hand side section of the lecture hall. One way Irena displayed her dissatisfaction was to deface the non-Jewish identification on her grade card. Later in life, Sendler claimed that she faced disciplinary measures due to her activities as a supporter of the Jewish community and for being a communist.

Irena joined the Union of Polish Democratic Youth in 1928. Later on, she joined the Polish Socialist Party and was refused repeatedly employment within the Warsaw school system due to the recommendations from the University of Warsaw which described her as radically leftist.

Fortunately, she was employed in a legal counseling and social help clinic, the pithily-titled “Section for Mother and Child Assistance at the Citizen Committee for Helping the Unemployed”. She tended to work in the field going in and out of Warsaw’s poorest neighborhoods until the government abolished her employment area.

The War

With the German invasion in full swing, on 1st November 1939 the German occupation authorities ordered that Jews were removed from the staff of the Social Welfare Department. This was the area where Sendler worked.

The German authorities also barred any assistance to Warsaw’s Jewish community. Sendler and her sympathetic colleagues began to help wounded and sick Polish soldiers.

It was during this time that Sendler initiated the idea to begin generating false medical documents for soldiers and poor families so that they could get aid from the government. She extended this cover to Jewish communities and institutions. Sendler led a small group to help Jewish families and children excluded from their department’s social welfare protection.

By November 1940, around 400,000 Jews were crowded into the small area named the Warsaw Ghetto which was sealed by the Nazis. Sendler was able to gain access to the ghetto through special permits granted by the Social Welfare Department which allowed her to check for signs of typhus.

Using this as a pretext to enter the ghetto, Sendler and colleagues brought in medications to the Jews. This soon progressed into smuggling Jews out of the ghetto and helping them survive elsewhere in the city. This was done at a huge risk to her own safety as from October 1941 it was punishable by death to give assistance to Jews in German-occupied Poland.

After World War II

During the Warsaw Uprising, Sendler worked in a hospital and helped Jews and Polish soldiers. However, after the war, the hospital ran out of resources. Sendler, hitchhiked to Lublin to gain funding from the communist government that was based there.

- Aimo Koivunen: Finland’s Drug-Fueled Super Soldier

- Cross-Dressing, Globe Trotting? The Extraordinary Jeanne Baret

She also helped to set up Warsaw’s Children’s Home and resumed her other social work activities. Through this work, she was appointed the head of the Department of Social Welfare in Warsaw’s municipal government.

In January 1947, Sendler joined the communist Polish Workers’ Party and remained a member of its successor, the Polish United Workers’ Party until it dissolved in 1990. Recent research suggests that in 1947, Sendler was the party executive.

From here, she held lots of high-level party and administrative posts throughout the Stalinist period. This included the Ministry of Education and the Ministry of Health.

In the Polish People’s Republic (1947-1989), Sendler received at least six decorations, including the Cross of Merit for her wartime saving of Jews, receiving another award in 1956 and eventually the knights cross in 1963.

However, she was quite forgotten about in the modern day until a group of American high school students in 2000 rediscovered her. Yad Vashem, Israel’s official memorial to the victim of the Holocaust, had recognized her efforts in 1965 and became an honorary citizen in 1996.

Irena Sendler’s achievements became well known in America when students from Kansas produced a play based on her life called “Life in a Jar”. This production was a success and was staged over 200 times in the US and contributed to getting Sendler’s story out there.

Her story is an incredible one of striving against adversity. It would have been easy for her to ignore the troubles that surrounded her. However, Sendler, perhaps inspired by her father, strove every day to recognize the evils of the world and combat them.

She became one of the most celebrated people in Poland and even received a letter from Pope John Paul II praising her efforts. She has received many of the awards that both Polish and Jewish organizations could grant her, and rightfully so.

Top Image: Irena Sendler in 1944. By this point she had saved thousands of Jewish lives. Source: Unknown Author / Public Domain.

By Kurt Readman