History is full of successful and powerful military leaders, but some rise above the rest. Alexander the Great almost conquered the world due to exceptional strategies and a never-ending charisma that motivated his soldiers to fight until they exhausted themselves completely.

There was Julius Caesar, who conquered all of Gaul in a short period of eight years. The infamous Genghis Khan used his knowledge of the terrain, relentless pursuit, psychological warfare, and diplomacy to create one of the world’s largest empires. These leaders are known by all, but others have been overshadowed for far too long.

Someone rarely discussed is the Czech Jan Žižka, a brilliant man who never saw defeat. Jan Žižka revolutionized warfare through the use of his war wagons and the adoption of mobile mounted cannons/use of gunpowder weapons.

He also was one of the first military commanders to look at and strategize with the artillery, cavalry, and infantry parts of his army as a single unit, and he did this despite losing first one eye, and then the other eye too.

How did a blind man with a rag-tag army defeat large organized armies across the lands of Bohemia?

Jan Žižka

Jan Žižka was a Czech general and military hero who is now considered a Czech national hero, a title he rightly deserves. Jan Žižka was born in the village of Trocnov in the Kingdom of Bohemia sometime around 1360.

He lost an eye at some point in his youth but when and how it happened is unknown. He was known as “One-eyed Žižka” and spent a few years causing trouble as a member of a gang of outlaws.

However, he gave up those activities when destiny came calling and he was appointed to the position of chamberlain (a trusted bodyguard and staff manager of the castle) of Queen Sofia of Bavaria. While in service of the queen, he would accompany her to hear the preachings of a man named Jan Hus.

Jan Hus was a Czech philosopher and theologian who became a Church reformer. He inspired Hussitism, which was a predecessor to Protestantism.

Jan Hus was popular in Bohemia, but the Catholic church hated him. Hus preached that supreme authority came from the Bible, not from the Pope’s hands. He was against clerical corruption and felt that everyone should be allowed to receive both forms of Communion (body and blood of Christ).

At that time, only the priests could receive the blood of Christ, which was unacceptable to Hus. Jan Hus also preached for church services to be given in Czech instead of Latin so that everyone could hear the word of God, not just the upper class.

- Sviatoslav of the Grand Kievan Rus: another Alexander the Great?

- England’s Great Outlaw, Robin Hood: Real or Legend?

Hus was therefore public enemy number 1 in the eyes of the church, and he was excommunicated in 1411. Accused of heresy, he was burned at the stake on July 6, 1415. This transformed Hus into a martyr in the eyes of his followers, who became known as Hussites.

The Hussites blamed the Holy Roman Emperor Sigismund for the death of Hus and were not shy about their feelings. Sigismund, for his part, detested the Hussites and wanted to see them destroyed. The Hussites of Bohemia were ruled over by Sigismund’s brother King Wenceslas IV of Bohemia, and there wasn’t much Sigismund could do at that point.

In 1417 a council of the Roman Catholic Church issued a blanket ex-communication to all Hussites. The Hussites responded to the announcement by forming strongholds to protect themselves from persecution. They were not going down without a fight.

Jan Žižka Leads the Hussites

In 1419, Jan Žižka joined forces with a Hussite priest. On July 20, 1419, Jan Žižka and the priest led a group of armed Hussite protestors through the streets of Prague down to New Town Hall. He demanded that a group of moderate Hussite prisoners be released from prison.

The pro-Catholic counselors in New Town Hall refused. So Jan Žižka and other Hussites threw the 13 councilors out of the windows, and the armed protestors killed the ones who survived the fall on the ground. This became known as the First Defenestration of Prague, and Jan Žižka was elected the captain of the Hussite forces in Prague.

However, this rather backfired when King Wenceslas was so alarmed by the riot and men being thrown out the windows that he dropped dead. With Wencelas’s death, the new King of Bohemia would be the heir to the throne, the Holy Roman Emperor Sigismund.

The Hussites were determined to do whatever it took to prevent Sigismund’s royal ascension. Soon, clashes between Hussites and Royalists (Sigismund’s supporters) began. Jan Žižka led operations against the Royalists by besieging the town of Nekmer. A local lord responded by gathering a force of 2,000 cavalrymen, sending them to silence Jan Žižka’s 400-strong infantry.

A Rare Genius

Jan Žižka’s troops of peasants were outnumbered five to one, but Žižka was a brilliant man who knew that medieval armies had zero strategies: training, and a well-timed charge was how most conflicts played out. Jan Žižka laid out a stringent code of conduct and discipline on those who fought under him, which meant they were easier to direct in combat.

Jan Žižka also took advantage of what “was readily available to him and his troops.” The peasants worked in fields threshing grain, and Jan Žižka took the threshers and transformed them into flails. The peasants were now armed, but then Jan Žižka moved on to buy crossbows and handguns with Hussite funds, further arming the outnumbered rebels.

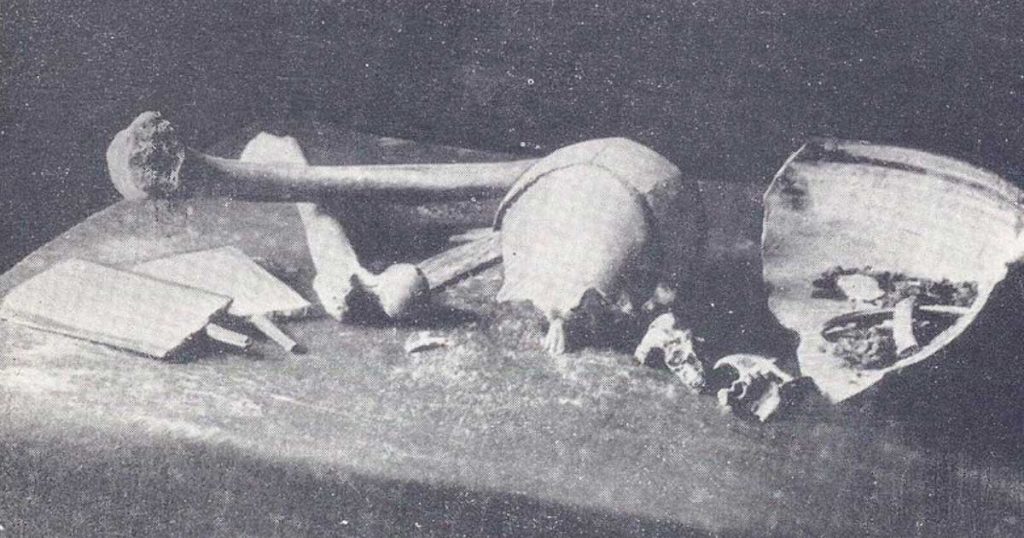

Buying weapons wasn’t all Jan Žižka did to prepare; he enhanced four-wheel wagons to turn them into war wagons. In each wagon, Jan Žižka assigned a crew of 20 soldiers: two armored drivers, two men with pavises (massive full-body shields popular during the 14th and 16th centuries), six crossbowmen, two men wielding handguns, four peasants with flails, and four men armed with halberds.

- William Tell: Is there a Real Man Behind the Myth?

- The Legend of Miloš Obilić: Did He Assassinate a Sultan?

The walls of the wagon were built up, and wooden panels attached to ropes were hung over the side of the wagon to protect the wheels. To prevent enemies from crawling under the wagons, Jan Žižka hung a wood plank to block the way. Holes were cut into the sides of the wagon’s walls large enough for crossbowmen and hand gunners to fire through at the enemy.

The crossbowmen and gunners firing from inside the wagon would take out cavalry riders. While the rest of the men would attack the unhorsed cavalrymen with their staff weapons, hacking them to death.

Wagenburg

Jan Žižka would arrange the battle wagons into a square shape called a wagenburg, which means “wagon fort.” Between each wagon, a cannon or men with pavises were stationed. Inside the square would contain the foot soldiers, cavalry/horses, as well as supplies.

The wagenburg was a very popular military tactic favored by the Byzantines, Goths, and Mongols and was incredibly effective. What made Jan Žižka so powerful was his consideration of the terrain he positioned his troops on.

Jan Žižka preferred to position his troops on the tops of hills with steep slopes, which forced the enemy’s cavalry to dismount and climb the hill on foot. When the 2,000-strong Royalist troops attacked Žižka’s 400-strong peasant army, they were crushed, and his victory led to a full-on war against the Hussites.

Jan Žižka’s victory in Prague allowed Žižka to lead his forces through Bohemia, which led to Sigismund losing control of the territory. Jan Žižka had yet to lose a battle, but in 1421, Žižka was badly injured and lost his remaining eye.

By this point, Jan Žižka was in his mid-50s and completely blind; it should have been the end of the Hussite forces, but it wasn’t. Jan Žižka was a total badass who continued to lead his troops relying on detailed descriptions of the terrain and combat during battles so he would know what was happening around him.

Even when infighting between different factions of Hussites began, Jan Žižka still was victorious, which led to peace between the arguing factions. Once the infighting had ended, blind Jan Žižka was made the leader of a new military campaign headed to attack Sigismund’s followers in Moravia.

Jan Žižka was finally defeated just outside the border of Moravia on October 11, 1424. It wasn’t combat that ended the life of the undefeated blind Hussite general. It was either the plague or an infected carbuncle.

Jan Žižka’s dying wish was “to have his skin used to make drums so that he might continue to lead his troops after his death.” His troops renamed themselves Sirotci, which meant “the Orphans” after Jan Žižka died, they all felt as if they had lost their father and were now alone. For a decade and a half after the death of Jan Žižka, the Hussite armies continued to defeat their foes, but infighting led to the end of the Hussite armies.

Top Image: Jan Žižka led a peasants’ revolt which challenged the Holy Roman Emperor himself. Source: Fxquadro / Adobe Stock.