Joseph Smith, United States founder of the Latter Day Saint movement more commonly known as the Mormons, was a creative man. His inspiration came from many places, and these included, somewhat oddly, ancient Egypt.

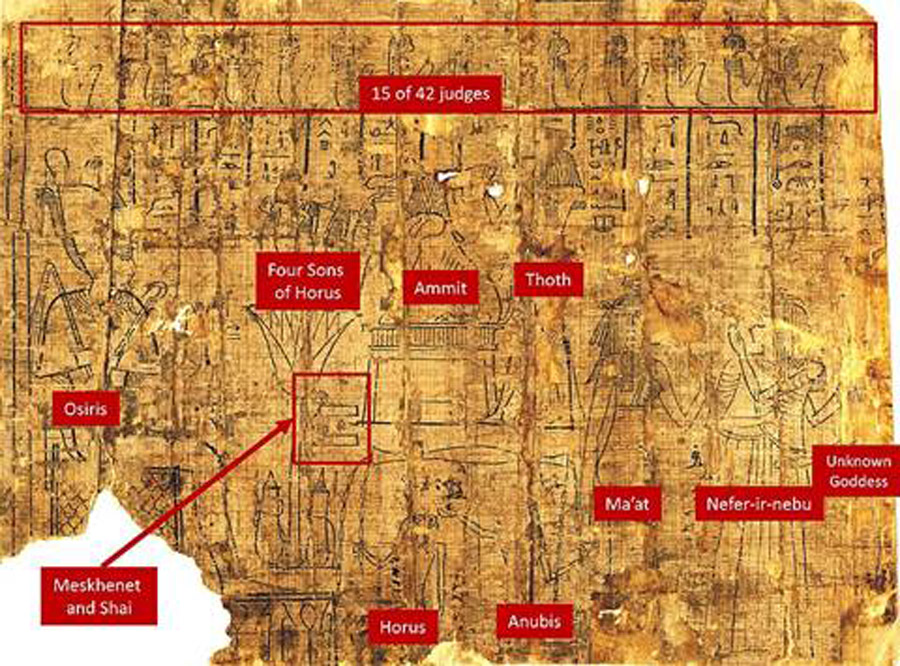

The theology may be questionable, but the source materials Smith used, Egyptian funerary papyrus fragments known as the Joseph Smith Papyri, were very real, and some survive to this day. Originating from ancient Thebes, they were formerly owned by Joseph Smith along with four mummies. According to Smith, the papyrus held the records of Abraham and Joseph, two ancient patriarchs well known from the Bible.

In 1842, Smith published the first section of what he claimed to be a translation of the Book of Abraham. Smith claimed the papyrus also contained another text, The Book of Joseph, but he never released a translation.

After a period in museums during which some of the fragments were lost, the Mormon Church purchased the remaining papyri in 1967. The papyri’s rediscovery spurred increased interest and research, as well as a decades-long discussion about their significance, their interpretation, and whether Smith really understood his source materials.

With these fragments being newly understood, is Mormonism a castle built on sand?

The Origin of the Fragments

All of the mummies and papyri were discovered in the ancient Egyptian city of Thebes, near Luxor, where they date to between 300 and 100 BC during the late Ptolemaic Egyptian period. The bodies and papyri were buried in the Theban Necropolis, presumably in the valley of the nobles, west of ancient Thebes.

One of the mummies’ scrolls has been identified as belonging to an Egyptian priest named Horos, who came from a prominent line of Theban Priests of Amun-Re in the worship of Min who slaughters his foes. His family tree can be accurately traced to eight generations and his existence is well attested.

While these are important artifacts, and certainly valuable, according to Egyptologists such finds are far from unusual. It seems rather that these were unique because of the man that owned them, rather than in and of themselves.

The two rolls, according to Joseph Smith, were physically authored by the ancient patriarchs Abraham and Joseph. Smith pointed to specific locations on the papyri and identified distinct hieroglyphics as Abraham’s signature.

The mummies however were even more impressive at the time, being sold to Smith as members of a royal household. Pharaoh Onitas, his wife, and their two daughters, one of whom was named Katumin, were the names Smith used to refer to them.

Smith, along with his mother Lucy Mack Smith, claimed that these names were revealed to them through a divine understanding of the artifacts. Mack Smith went even further, referring to one of the mummies as the daughter of pharaoh who saved Moses, and also named the pharaoh Necho.

Unfortunately, divine insight is no match for rigorous archaeology, and in this instance it seems Smith and his mother were mistaken. The mummies in reality are thought to be priests and aristocrats from Egypt’s ruling classes, based on where they were discovered and the writings found on them.

There are no known pharaohs or their family members with the names Onitus or Katumin. Although there was a Pharaoh Necho, he was buried in Sais, near the Nile Delta, far from where the mummies were discovered. It would be churlish to suggest that Smith fabricated his understanding of these mummies and papyri to attract supporters, but that is certainly how it seems.

What do Mormons Believe?

The Book of Abraham, as translated by Smith, has been a topic of debate since its release in 1842. Since the late 1800s, non-Mormon Egyptologists have disagreed with Joseph Smith’s explanations of the facsimiles. They further claim that damaged pieces of the papyri have been reconstructed incorrectly.

Arthur Cruttenden Mace, Assistant Curator in the Department of Egyptian Art at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York, released a letter about the Book of Abraham in 1912. When fragments of the Joseph Smith Papyri were discovered in the late 1960s, the debate heated up.

Both Mormon and non-Mormon Egyptologists have translated the papyri, but neither of their translations do not match the wording of the Book of Abraham as reportedly translated by Joseph Smith. Indeed, even the name Abraham does not appear in the papyri once they have been accurately translated.

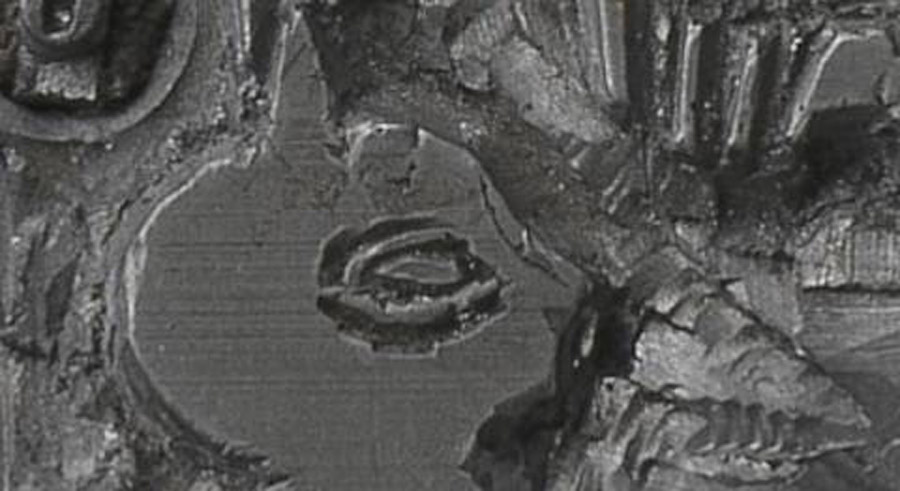

Worse, the depictions of some of the artifacts appear to have been altered to closer fit the narrative proposed by Smith. In particular a depiction of Anubis, the Egyptian jackal headed god of the dead, appears to have been changed by scraping off the nose so the figure now can appear to be Abraham.

The Mormons, alarmed at what appears to be evidence of blatant fabrication at the heart of their church, have done their utmost to address the two main issues with the Book of Abraham papyri. The papyri are neither old enough to have been written by Abraham and Joseph, and the papyri say nothing about Abraham and Joseph.

In fact, if the text was indeed what Smith claimed then the papyri would be the oldest extant manuscript linked to the Bible, anywhere. Mormon prophets and instructors have long insisted that the papyri purchased by Joseph Smith were the genuine article, drawn and written directly by Abraham.

This claim was often reaffirmed to early believers. However what has not been offered is any proof other than a belief in the honesty of Smith. And the two main questions remain unaddressed and, to an extent, sidelined.

A More Rational Explanation

In understanding this inconsistency, the answer seems not to lie with interpretations of the papyri, but with Smith himself. He was known to use whatever old documents he had on hand to provide credibility to his claims, such as with the Book of Mormon.

Further, his translations were sometimes not based on any physical records which were generally claimed to have been lost by Smith. However, the survival of the papyri in this instance and the egregious fabrications they highlight throw doubt on the veracity of anything else Smith wrote, or claimed.

According to some evidence, Smith did make attempts to master the Egyptian language and studied the manuscripts closely. In July 1835, he was constantly occupied in translating an alphabet to the Book of Abraham, and arranging a grammar of the Egyptian language as practiced by the ancients, according to his biography.

This grammar, as it was known, consisted of columns of hieroglyphic letters followed by English translations written by Joseph’s scribe, William W. Phelps, in a big notebook. Egyptian characters are followed by explanations in another text produced by Joseph Smith and Oliver Cowdery.

While there may have been a genuine attempt to understand the artifacts, the fact that these books do not match the papyri text in any way undercuts Smith’s attempts at genuine research. If he had learned anything of ancient Egyptian writings, by the time he compiled his own interpretation he had clearly forgotten.

A Lie?

The papyri moved through numerous hands after Smith’s death; they are thought to have ended up in a museum in Chicago, where they were believed destroyed in the Great Chicago Fire. However, not all of the pieces were burned, and the Metropolitan Museum of Art acquired part of them in 1947.

The scholarly argument over the book’s translation and historicity cannot find any validity and worth of the book of Abraham as a translation of these surviving fragments. While the Mormons may find inspiration in Smith’s teachings, for the rest of us this seems altogether too shady.

Top Image: One of the surviving fragments. The sketched head of the standing figure is incorrect, and figure should be Anubis. Source: Unknown Author / Public Domain.

By Bipin Dimri