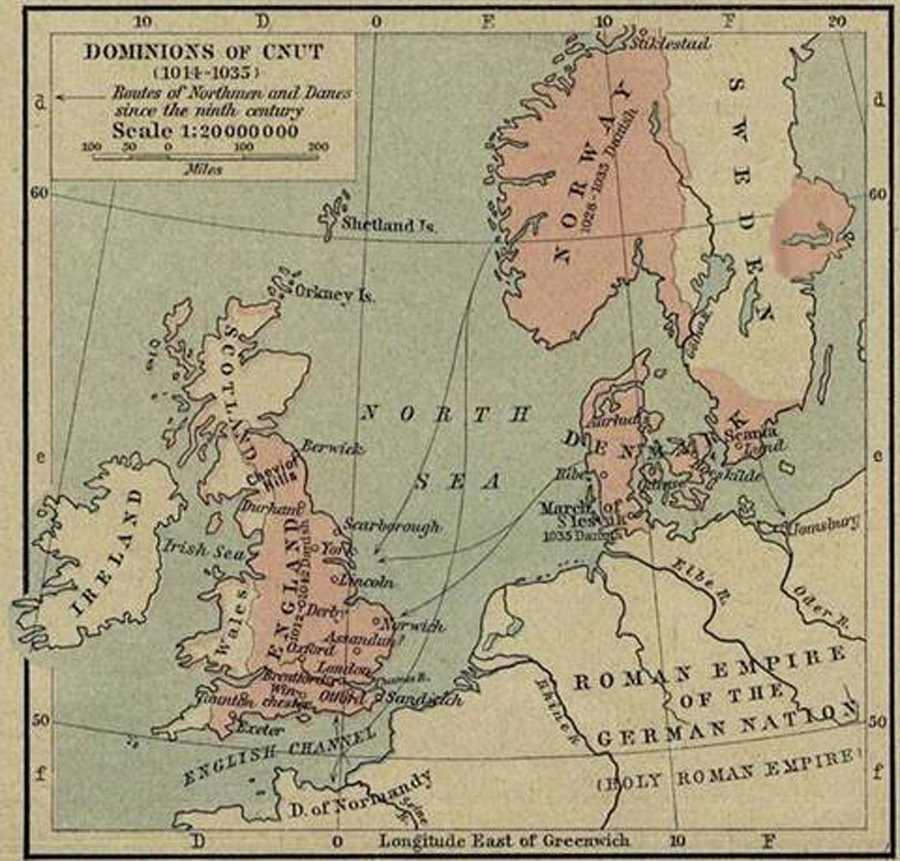

Who was King Cnut? Also known as Cnut the Great, this powerful ruler was King of England from 1016, King of Denmark from 1018, and King of Norway from 1028 until he died in 1035. The three kingdoms united under Cnut’s rule are referred to as the North Sea Empire.

Through inheritance and conquest he won a huge European kingdom for himself, becoming one of the most powerful men in Europe in the process. And yet the single thing about Cnut that is remembered by most is that, driven to arrogance by his glorious successes, he believed himself master of the weather and the waves and tried to prevent the incoming tide through sheer force of will.

Was this a man so confident in his abilities that he made a fool of himself? Who was this great leader, and what led to the story?

From Danish Prince to King

Canute was highly born, heir to the Danish throne and also the grandson of the Polish ruler Mieszko I on his mother’s side. As a youth, he accompanied his father Sweyn I Forkbeard, who was the king of Denmark, on his invasion of England in 1013.

Sweyn was accepted as king of England by the end of 1013 but did not rule for long, dying in February 1014. At that point an English faction sympathetic to Sweyn and his son invited Cnut to return.

As a Danish prince, King Cnut won the throne of England for himself in 1016, two years later. By this time Vikings had been harrying northwestern Europe for centuries, and for a war leader to win a kingdom in this way was obviously not unheard of in the British Isles.

His later accession to the Danish throne in 1018 brought a combination of the crowns of England and Denmark. Cnut sought to keep this power-base by unifying Danes and English under cultural bonds of wealth and custom, as well as through mercilessly crushing any signs of dissent.

After a decade of conflict with different opponents in Scandinavia, Cnut additionally claimed the crown of Norway in Trondheim in 1028. The Swedish city Sigtuna was also apparently held by Cnut as coinage struck there names him as king, but there is no narrative record of his occupation.

In 1031, Malcolm II of Scotland also submitted to him, though Anglo-Norse influence over Scotland was weak and ultimately did not last until Cnut’s death. But from this point until his death in 1035, Cnut ruled a vast conglomeration of kingdoms, all swearing fealty to him.

The Reign of King Cnut

Canute’s first actions were ruthless as he gave Englishmen’s estates to his Danish followers as rewards; he engineered the death of any possible rivals to the crown and had some prominent Englishmen killed or outlawed.

In 1016, Canute had given away the earldom of Northumbria to the Norwegian Viking Eric of Hlathir, and in 1017 he put the renowned Viking chief Thorkell the Tall over East Anglia. Yet Canute did not carry forward his rule like a foreign conqueror for long: by 1018, Englishmen were permitted to hold earldoms in Wessex and Mercia.

The Danish element in his entourage also steadily decreased as he became more and more “king of England”. Theories suggest that it was likely Wulfstan, an English bishop, who aroused in the young Canute an ambition to emulate the best of his English predecessors, especially King Edgar.

Canute proved to be an effective ruler who brought internal peace and prosperity to the land. He became a strong supporter and a generous donor to the church, whose sympathy towards the king was boosted by a pilgrimage to Rome, during which he attended the coronation of the Holy Roman Emperor.

- The Suspicious Death of William II: Who Killed the Rufus?

- Thick Skinned: Why Did Vikings Really Cover Their Shields with Leather?

He secured from the latter and other princes whom he met reductions in tolls for the English traders and pilgrims. Denmark benefited from the establishment of his friendly relations with the emperor. He surrendered Schleswig and territory north of the Eider River when negotiations began to marry the emperor’s son Henry to Cnut’s daughter Gunhild.

However this moment of prosperity was not to last. Neither Cnut’s illegitimate son Harold, who ruled England until 1040, nor his legitimate son Hardecanute, who succeeded to Denmark in 1035 and England in 1040, inherited his qualities. The English reverted to their old royal line back in 1042, and Denmark was passed to Sweyn II, son of Earl Ulf and Estrid.

A Man Who Believed He Could Hold Back The Tide?

When we come to the story of the tide however, we are on less firm ground. In the end, it seems that the story of King Cnut and the tide is an apocryphal anecdote illustrating the need for piety or humility, as recorded in the 12th century by Henry of Huntingdon.

Henry tells the story as one of three examples of Cnut’s “graceful and magnificent” behavior, outside of his bravery in warfare. The other two are his arrangement of his daughter’s marriage to the later Holy Roman Emperor and the negotiation of a reduction in tolls on the roads across Gaul to Rome at the imperial coronation of 1027.

Canute set his throne by the seashore in Huntingdon’s account and commanded the incoming tide to halt and not wet his feet and robes. Yet the tide did not hear him and continued to rise, washing over his fine robes and shoes.

It seems it is the interpretation which has gone awry in the centuries since the story was written. According to some versions, King Cnut was not acting in arrogance, but instead clearly aware that the tides would not obey him and staged the scene to rebuke the flattery of his courtiers.

Such we should expect from our leaders.

Top Image: Cnut attempts to hold back the waves. Source: R E Pine / Public Domain.

By Bipin Dimri