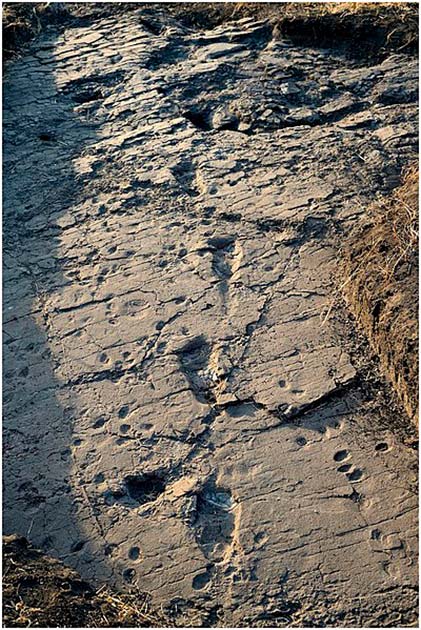

In 1976 archaeologists working in Laetoli, Tanzania made an amazing discovery. They found a series of prehistoric footprints that turned out to date back 3.7 million years.

These prints, preserved in a thin layer of volcanic ash, appeared to be human, indicating an early hominin had made them. The problem was this contradicted pretty much everything we thought we knew about early human evolution and when our ancient ancestors first walked upright on two feet.

For decades arguments raged in scientific circles as to what really made the Laetoli footprints. Only in 2021 a group of paleontologists claimed to have solved the mystery once and for all.

The Discovery

Interestingly, and confusingly, footprints have been found at two sites at Laetoli, sites A and G. The footprints at site A were found first and the first man who studied them, paleoanthropologist Mark Leakey, wasted no time in declaring they had been made by hominins (some of our earliest ancestors).

The problem was that the footsteps indicated a strange gait known as cross-stepping, a form of walking that no form of human has ever used. Things were then complicated further when researchers found more ancient footprints at site G.

The footprints at site G were so clearly human in origin that they called into question Leakey’s original hypotheses even further. It was clear that not only did the site A steps cross-step, but they were also a weird shape that researchers called “most unusual” and “curiously shaped.” Everyone agreed that they had been made by some kind of mammal walking bipedally but couldn’t agree on which mammal.

Things quietened down a bit until 1987 when another paleoanthropologist, Russel Tuttle, waded in with a paper suggesting three different hypotheses. First the site A prints had been disrupted by the passage of time, which is why they made no sense. Second, they were made by a young bear walking upright. Or third, they were made by a previously undiscovered species of hominin.

Tuttle decided his second hypothesis was the strongest and ran with it. He studied modern circus bears that had been trained to walk on two feet and found their prints were remarkably similar to the site A prints. A great start.

- Bolivia Dinosaur Footprints Wall at Cal Orcko Cretaceous Park

- God and the Dawn of Man: Did Homo Erectus have its Own Religion?

These findings meant that many decided that Tuttle’s theory was actually fact. But there were problems with the bear theory. For example, the fact that the width of a bear’s steps didn’t match the Laetoli footprints.

Tuttle wasn’t even convinced he was right. He tried to make it clear that much more research needed to be done before a decision could be made. Other paleontologists, like Tim White and Gen Suwa agreed. They felt that the footprints needed a thorough cleaning before a reliable identification could be made.

Fast forward to 2019 and a new team, led by Ellison McNutt of Ohio University, decided to do just that. They worked diligently to remove infill from the site A prints and what they found was groundbreaking.

Disproving the Bear Theory

While the team couldn’t safely remove the infill from all five prints, they did manage to unveil morphological details that the previous researchers hadn’t been able to access. Their findings led them to definitively disprove the long-accepted bear theory. Much of this revolved around the discovery of a second digit that had been obscured by infill.

Realizing they were onto something; McNutt’s team began working with an animal rehabilitation center in New Hampshire. They recorded 50 hours of wild black bear footage and found only three minutes of footage where the bears engaged in unsupported bipedal standing and walking. In other words, the bears only walked on two feet around 0.1% of the time.

Furthermore, only once did a bear take four unassisted bipedal steps in one go. Whatever had made the tracks at site A had managed at least five. Bears would have also left claw marks, something the site A prints lack. These facts made it look increasingly unlikely that a bear had left the footprints.

Perhaps the biggest nail in the theory’s coffin however is that 85 mammalian species are known to have walked the Laetoli landscape 3.6 million years ago. None of them were bears. No bear remains have ever been found close to the site.

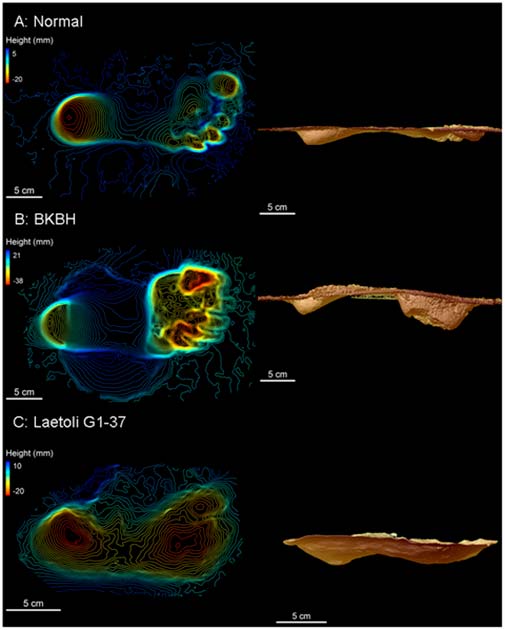

These findings spurred McNutt’s team to use 3D photogrammetry and laser scanning technology to make precise measurements of the site A footprints. These were then compared to data already collected on bears, chimps, and humans.

This comparison showed that while it wasn’t impossible that a bear had made the prints it was much more likely a human had made them. In particular, the toe and heel impressions were much wider and flatter than a bear’s and more akin to a human.

But it wasn’t just the shape that was human. While humans don’t naturally cross-step, McNutt’s team noted that we’re known to do it to regain lost balance. Bears, however, are incapable of doing so- their joints just won’t bend that way.

All this information led McNutt’s team to conclude the tracks were in fact made by a hominin. Unfortunately, this raised as many questions as it answered for the team.

The tracks at site G, the obviously human ones, are believed to have been made by a group known as the Australopithecus Afarensis species. But their prints are completely different from the site A prints. Why the discrepancy? It could be that the group at site A suffered from a physical deformity. Perhaps deformed hips or knees had affected their gait.

McNutt’s team settled on a much more exciting theory, however. Their paper, released in 2021, states “a minimum of two hominin taxa with different feet and gaits coexisted at Laetoli.” In normal speech, they believe that two species of hominin were in Laetoli at the same time.

Back Where We Started

So, the case is solved, right? Not exactly. Like any research paper that makes bold, history-changing claims, this one is being questioned. Rightly so.

No one is really questioning whether or not the bear theory has been disproven, McNutt’s team has succeeded in that. They’re less convinced though that the team has managed to prove two different species of hominin walked Laetoli at the same time. There just isn’t enough evidence, yet.

The fact is five footprints just isn’t a lot to go on and it’s likely a definitive answer to this mystery won’t be found unless more evidence is dug up. Still, thanks to McNutt and his team’s work we’re one step closer to knowing what made these peculiar footprints.

Top Image: The Laetoli Footprints are thought to be the earliest evidence of humans walking on two legs. Source: Tim Evanson / CC BY-SA 2.0.