“I want to remain an eternal mystery to myself and others”, stated King Ludwig II of Bavaria. What happened when the king’s fairy-tale world and his role as monarch collided?

For many, the Bavarian castle of Schloss Hohenschwangau would seem a beautiful place to grow up. Perched high atop a mountain amidst stunning natural scenery, the castle seems every inch a fairy-tale palace.

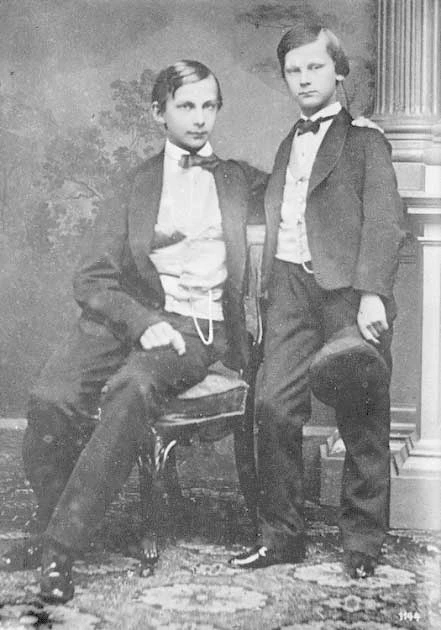

But for Prince Ludwig II, the castle was the furthest thing from the idyllic setting it seemed to grow up in as a royal prince. He was educated to adhere to a rigid regimen from his birth in 1845. On the advice of their advisors, his mother, Marie of Prussia, and father, King Maximillian of Bavaria, kept a distance from Prince Ludwig and his younger brother, Prince Otto.

Thrust into the Real World

To keep the monarch focused on his duty to rule, a study and exercise regimen was created. Duty could make or break a king, and after failing to perform his duty during the German Revolution in 1864, his father abdicated. Ludwig was crowned King of Bavaria in the same year as he reached adulthood.

The people of Bavaria greeted the young, attractive king with open arms, especially the women who were attracted by his person as much as his position. But Ludwig had ascended to the throne at a perilous time: two years after becoming king, Bavaria and Austria had succumbed to Prussia in battle. Despite the fact that Bavaria had been granted some autonomy under the new Imperial Constitution, they were compelled to unite with twenty-one other monarchs to form the German Empire.

The monarchy had been constitutional up to this point, possessing of some but not entire influence; after this defeat, it had even less. Because of this early defeat, Prussia gained a lot of influence over Bavaria’s foreign policy and its young king.

The Fantastical World of Ludwig II

Ludwig didn’t do much differently as an adult from the boy his mother had described as a youngster who liked to put on plays, recite poems, and gift people money and property. He was frequently known to as the Swan King or, more famously, Der Märchenkönig (literally, “the Fairy Tale King”).

Uninterested in matters of the state he turned his attention to his fascination with French culture, which he idealized in his mind’s eye. Unhappy with how Bavaria was lacking in rich art, architecture, and music, he set out to build a multitude of fantastical castles, many taking their influence from the great French Palace of Versailles.

- Crown Prince Rudolph And The Mayerling Incident: Suicide Or Murder?

- The Suspicious Death of William II: Who Killed the Rufus?

Amongst his extravagant art projects, he constructed the castles of Neuschwanstein, Linderhof, and Herrenchiemsee. The king opted to hire theatrical set designers to construct the fortresses, making them all fantastical and far from reality. These castles were fictions, false battlements and vaulted ceilings held together with hidden wooden substructures. But they seemed every inch the perfect palaces Ludwig wanted them to be.

He had spent his days as a boy in Hohenschwangau Castle surrounded by the heroic German tales portrayed in the frescoes that adorned the castle’s walls. Ludwig was undoubtedly greatly affected by the artwork “Lohengrin” (“King of the Swan”) as he named one of his castles Schloss Neuschwanstein, meaning, “New Swan Stone Castle”. It was no coincidence this was the name of the castle owned by the Swan Knight Lohengrin in Richard Wagner’s famous opera.

Ludwig and Wagner

Richard Wagner’s music and operas fascinated Ludwig, who summoned the composer to a meeting with him in Munich in 1864. Many people credit the monarch for saving Wagner’s career by inviting him to stay in Munich and continue composing under his royal patronage.

Owing debts to numerous parties Wagner was at this point in his life only one step ahead of his creditors. His invitation to Munich was the narrowest of escapes from poverty or, worse, ending up in the hands of the many people he owed money to.

After his meeting with the king the composer wrote, “… Today I was brought to him. He is unfortunately so beautiful and wise, soulful and lordly, that I fear his life must fade away like a divine dream in this base world … You cannot imagine the magic of his regard: if he remains alive it will be a great miracle!”

The conservative residents of Munich, the state’s political capital, disliked Wagner and found his extreme anti-Semitism and philandering disturbing. Wagner’s life of opulence, luxury, and gossip was however short-lived, as Ludwig ordered him to leave six months after he arrived since his political views did not align with those of the Bavarian administration.

Forsaking his duty to his people and political alliance with his government the king continued to financially support Wagner. Completely caught up in the magical realms of Wagner’s operas, Ludwig confided in the composer that he planned to abdicate and join him. Wagner, alarmed at such a suggestion, shook the king out of his daydream and reminded him of his duty to his country and people.

Ever Deeper into a Fairy Tale

Ludwig’s self-perception was impacted by the fact that, as a constitutional king, he had limited influence over significant issues. A king in name but not in the original sense, he was left with a sense of estrangement from the position he occupied.

- The Duke of Buckingham: Was Dumas’s Hero also James I’s Lover?

- Nonsuch Palace: What Happened to Henry VIII’s Lost Castle?

The monarch gradually spent more time alone in his fantasy castles in an effort to create fairy-tale settings where he would feel like a real-life king rather than in Munich. He was enchanted by the belief that he must seem to be a king, creating the appearance of a magical kingdom and a holy one by the grace of God.

But his vision was expensive. His cabinet of ministers did not see eye to eye with Ludwig and had attempted to stop him from seeking loans from foreign ministries to construct yet more fantasy castles. Things came to a head and, sensing that he was about to dismiss the ministers in favor of a new cabinet, Ludwig’s parliament acted first.

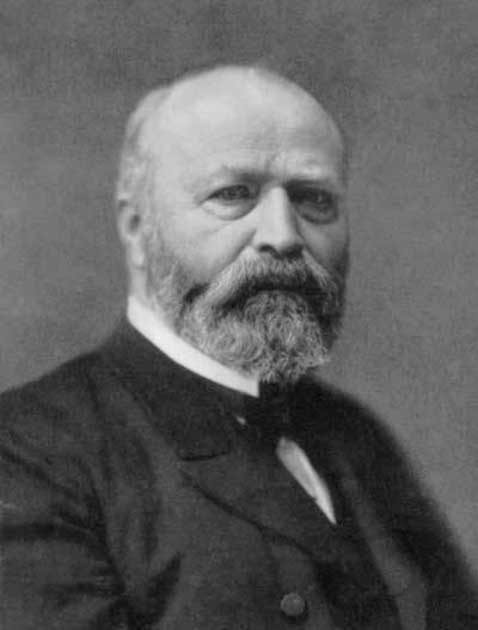

The chief physician at Munich Asylum, Dr. Gudden, was tasked with quietly compiling a medical report outlining the king’s mental state. He deemed Ludwig insane, largely on the basis of rumors: examples of his bizarre actions were cited such as his pathological shyness, eating outside in the cold, avoiding state business, slobbish table manners, and violence toward servants.

The Fantasy is Destroyed

On June 10th 1886, a medical report declared that the king was, “Suffering from such a disorder, freedom of action can no longer be allowed, and Your Majesty is declared incapable of ruling, which incapacity will be not only for a year’s duration but for the length of Your Majesty’s life”.

Berg Castle, located south of Munich on Lake Starnberg, served as Ludwig’s prison. The night after his incarceration, Ludwig went for a stroll around the castle grounds with his physician, Dr. Gudden. This was the last time the 40 year old king or his doctor were ever seen alive.

The two men’s corpses were discovered in Lake Starnberg a few hours later. Although his death was ruled a suicide, the king was oddly discovered in only waist-deep water, and an autopsy showed that he had no water in his lungs. Even stranger, Dr. Gudden’s autopsy revealed that he had been strangled and had suffered a blow to the head.

The notes that the king’s personal fisherman, Jakob Lidl, left behind have sparked one explanation about the king’s demise. He claimed to have been waiting by on a boat, prepared to row the king to safety. However, just as Ludwig climbed onto the boat, a shot was fired from the opposing bank, instantly killing him. Is it conceivable that the king’s autopsy, which failed to report any wounds or scars on his body, was falsified?

It seems obvious that the king’s death, whether it was caused by murder or suicide, was a direct outcome of his own unceasing desire to establish a perfect mythical kingdom. The Swan King could never exist as anything other than a fantasy character.

Top Image: Ludwig’s great castle Neuschwanstein, every inch the fairy-tale palace. Source: Savvapanf Photo © / Adobe Stock; Unknown Author / Public Domain.

By Roisin Everard