The ancient Celts of Ireland and Scotland observed the seasonal changes with Pagan community festivals in honor of their gods. As people who depended on the bounty of nature, celebrations around the annual harvesting of crops were momentous. Between the Summer Solstice and Autumnal Equinox, around the first of August, the whole community took part in the huge festival of Lughnasadh (Lughnasa).

Lughnasadh marked the first grain harvest of the year. Public domain.

The Celtic Wheel of the Year is an ancient Pagan calendar that indicates the annual cycle of seasons and festivals. On it, Lughnasadh, also known as Lammas, is one of the four Celtic fire festivals or cross-quarter days, including Samhain (Oct. 31), Imbolc (Feb. 1), and Beltane (May 1). These occur between the Solstices and Equinoxes, also known as the quarter days.

Origins of Lughnasadh

Brón Trogain, or “Sorrow of the Earth,” may have been the original word for what became the Celtic August festival (Daimler). There is uncertainty about when the term Lughnasadh originated. It stems from Lugh, the Irish god of war and oaths. He is an important member of the Tuatha Dé Danann, the pantheon of Gaelic Ireland. Násad is the Gaelic word for commemoration or an assembly or feast. Some sources interpret Lughnasadh as the “Marriage of Lugh.” Many Neopagans associate Lugh with light and the Sun, although some scholars dispute this.

Celtic Goddess Brigid the Enduring Deity

Celtic legend states that the king and great warrior, Lugh, first instituted Lughnasadh as a festivity of athletic strength games, weapons mastery, bardic competitions, and horse races. He wanted to honor his foster-mother, the goddess Tailtiu, who had died from clearing the land for the people to grow crops. Thus, Lugh chose Teltown in Ireland as the site of the first celebration. Every summer thereafter, the whole countryside held celebrations in Tailtiu’s honor on August 1 and they called them Lughnasadh. Therefore, the harvest festival also relates to the funerary games played in honor of Tailtiu.

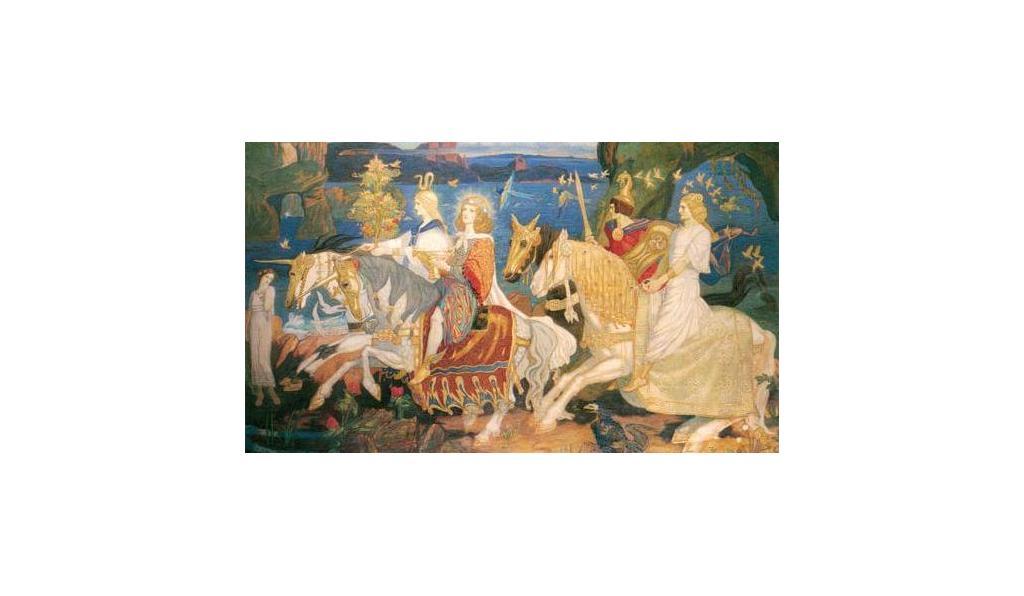

The Tuatha Dé Danann. Lughnasadh was named after the god Lugh. Public domain.

However, villagers also celebrated in honor of Lugh, who had acquired the knowledge of when they could plow, sow, and harvest their fields. Because of this legacy that he left behind, the harvest festival became interwoven with the legendary god Lugh.

The Celtic Prince of Lavau and His Opulent Tomb

Symbolism of the Harvest Festival

The cyclical nature of life, growth, death, and rebirth was a pervasive theme among the Celts. The harvest festival reflects this at a time when the first wheat is ready for the sickle and the life-producing season gives way toward the cold, lifeless, contracted winter when most things upon the earth die. Thus, the August festival does not only celebrate the bounty of the harvest but also laments the declining summer.

Lughnasadh celebrates the cycle of life and summer’s bounty.

The White Goddess website provides an explanation for Lugh’s association with the harvest festival. In the mythological tale, The Wheel of the Year, the Sun god puts his energy, light, and power into the crops growing in the plains. When the grain is harvested, the god is sacrificed and “we have a dying, self-sacrificing and resurrecting god of the harvest, who dies for his people so that they may live.”

Practices During the Lughnasadh Festival

Many details of ancient harvest rituals are lost, but research and recent celebrations provide hints at early traditions. Pre-Christian practices evolved as Christianity supplanted Pagan traditions. According to tradition, initially, the Irish kings organized large assemblies that involved games, feasting, religious rites, and political and business meetings. Horse races were held and the sacrifice and feast of a bull propitiated the gods and reaffirmed the king’s authority as a generous and benevolent ruler. (Tairis).

The first fruits of the harvest were offered up to the gods in thanks. As the crops were gathered, villagers said prayers for a successful harvest. On the other hand, they gave pleas of repentance if crops were poor. Bilberry picking, dancing, and pilgrimages to wells or mountain tops were also common. Additionally, a commercial aspect developed in which goods were sold and traded.

Alexander Carmichael, writing in the 19th century, recorded some of the harvesting rituals he saw practiced in the Scottish Highlands and islands of that time:

“The whole family repaired to the field dressed in their best attire to hail the God of the Harvest. Laying his bonnet on the ground, the father of the family took up his sickle and, facing the sun, he cut a handful of corn. Putting the handful of corn three times sunwise round his head, the man raised the…reaping (cry). The whole family took up the strain and praised the God of the Harvest.

Protection of the Corn Maiden

The harvest was laborious, and, thus, completion of the work held great importance. In many areas of the Celtic lands, rituals followed the cutting of the final sheaf – the bundle of stalks tied together – in the cornfields. In some places, this sheaf was dressed in clothes and dubbed the Corn Maiden (or Corn Dolly). Householders placed their corn dolls in a distinct location such as the kitchen, hearth, or even the local parish church. This way, she could provide protection throughout the cold winter and usher in the warm days of spring. Once spring arrived, the Corn Maiden was given to the horse on the first day of plowing.

The corn dolly embodied the “spirit of the grain.”

In other places, such as the Islands of Scotland, the sheaf took on a more menacing aspect. It was a bad omen to be the last man in the community to finish harvesting. Therefore, out of this belief grew an odd custom. Once the farmer cut the last ear of corn from that year, a rider on horseback would throw it into the field of a family who had not finished harvesting. This was a curse and an insult. If the rider was caught, the angry family might punish him by stripping his clothes off and shaving his hair and beard. Then they sent him home in that dishonorable and embarrassing condition.

A Time for Matchmaking

One important aspect of Lughnasadh is matchmaking, fertility, and temporary marriages. People called these “handfastings” or “Teltown marriages.” In these events, spouses selected each other deliberately or by rituals of chance. In one place, a temporary wall was built with a hole in it. Men and women gathered on either side and would reach through and become “married” to the person who grabbed their hand.

These unions, depending on the tradition of the locale, could last until Beltane (May 1) or until the following Lughnasadh. At that time, the pair would return to the exact spot where they took up their union. If they desired, the pair could enact a divorce by simply walking away from each other. Alternatively, they could make their marriage permanent.

Alexander Carmichael observed that the people had a custom in which they would auger who would get married, who would stay single, and even who would die. First, they would throw sickles high into the air and watch how the came down. Where the sickles fell and how they hit the ground gave them the insight into their matchmaking.

The Christian Evolution of Lughnasadh

Once Christianity came to the Celtic lands, many church Holy Days merged with the native festivals. This was certainly true of the harvest celebrations. The observances of the Feast of St. Mary (August 15) and St. Barr’s Day (September 27) took on some of the old harvest festival rituals.

Even the secular Puck Fair in County Kent (August 10 to 12) belies some harvest origins. A goat receives a crown as King of the Fair. Additionally, the buying and selling of livestock are mixed with the festival’s merriment. The Book of Leinster from the 12th century mentions a church festival held August 1 to 6 every three years at Carmun. There, the celebration featured horse races, feasts, and various entertainments.

A goat gets a crown and is everyone worships him as a king for three days at the Puck’s Fair.

The most notable blend of the archaic and churchly, however, is St. Michael’s Day, September 29th. St Michael was a favorite of the Celts. He is the patron saint of horses and the sea, both of which were mainstays of the Celts’ livelihood. St. Michael quickly became enmeshed in the mythology of the Celtic gods Lugh and Brian. Also, his feast day became almost a sanctified Lughnasadh. St. Michael’s Day festivities included horse races, the harvesting of carrots, and the exchange of carrots as gifts between sweethearts.

In Preparation for Fall and Winter

After the celebrations, the work of harvesting and the storing of crops continued as long as the weather allowed. But villagers had to complete all work before the cold days arrived and families settled in for the winter. The next seasonal festival, the shadowy Samhain on October 31, would shatter the walls between this world and the Afterworld. All crops harvested after that ominous date were believed to carry evil.

Lughnasadh is still observed today. Crom Dubh Sunday, Bilberry Sunday, or Puck’s Fair are just a few names of the celebrations. Events may include the old rituals such as cutting of the first grain, feasting, and the lighting of bonfires. The spirit of the festival still embodies thanks for a bountiful harvest and preparation for the cold and dark days to come.

References:

“Celtic Heritage”, Aug/Sep 1996.

Daimler, Morgan. “Irish-American Witchcraft: Brón Trogain – Lúnasa By Another Name.” Agora. July 24, 2015.

“Deeper Into Lughnasadh”, the Order of Bards, Ovates & Druids website.

Lammas – The Wheel Of The Year – The White Goddess, n.d.

“Lúnastal.” Tairis, n.d.