In the northwest of France, there is a city by name of Le Mans, which is known for little more than a famous car race that takes place once a year: the “24 Hours of Le Mans.” But with a cursory glance at Wikipedia’s entry of “Le Mans” in the section of Notable People, one will see in the 7th position down, amidst twenty various aristocrats, priests, and famous musicians, the names of Christine and Léa Papin. These sisters gifted the city with a degree of infamy that would otherwise never have been achieved. But instead of being known for a grand and auspicious accomplishment, the Papin sisters are notable only for murder, in a most gruesome way, their domestic employer and her daughter in 1933.

The Papin Family

The Papin sisters came from a troubled family in Le Mans. Their mother was Clémence Derré and their father was Gustave Papin. Although rumors were going around town that Clémence was having an affair with her boss, Gustave loved her. In October 1901, when she became pregnant, Gustave married Clémence. Baby Emilia Papin arrived in February 1902. But, Gustave had always wondered if Clémence was still having an affair. He decided he would get a job in another town to take Clémence away from Le Mans.

About 2 years after Emilia was born, Gustave announced that he was taking a new job in a different town. Clémence threatened to commit suicide rather than leave Le Mans, and this only served to strengthen Gustave’s suspicion that she was indeed having an affair. After she regained her senses, the couple moved and started a new life.

The relationship was becoming progressively more volatile; reports indicate that Clémence showed no affection for her children or her husband and that she was an unstable individual. Gustave turned to alcohol. When Emilia was 9 or 10 years old, Clémence sent her to the Bon Pasteur Catholic orphanage. Later, information surfaced that her father had raped her. Emilia Papin later joined the convent and became a nun. However, Clémence had also given birth to two other children, both of which, she and her husband had sent away at an early age.

The Papin Sisters

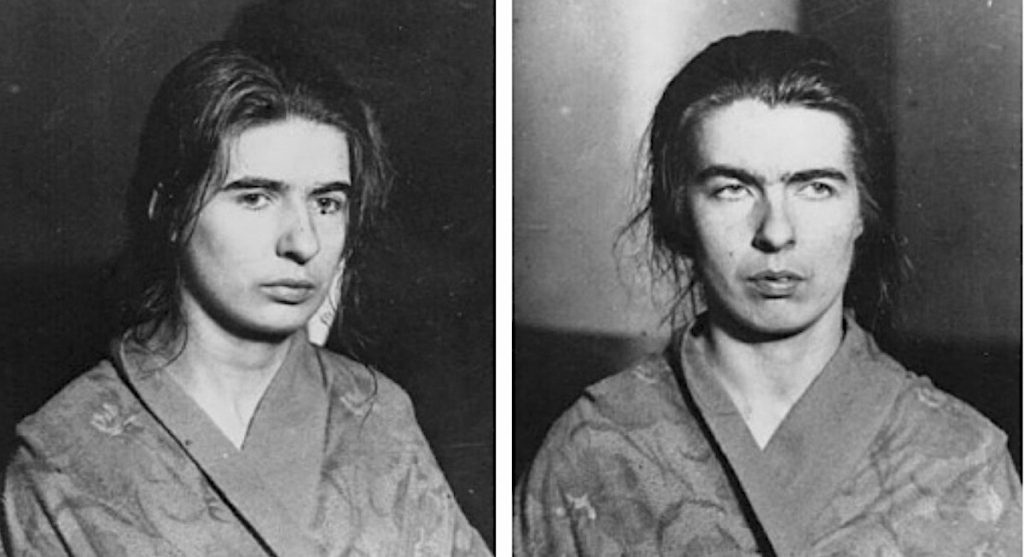

Christine was the difficult one. She was born in 1905 and was the middle child of the family. Soon after she was born, Christine’s parents gave her to her father’s sister, who was happy to have her. Christine remained with her aunt for seven years, after which she entered a Catholic orphanage. Although Christine wanted to join the convent, her mother would not allow it, and later placed her into employment. With an average intelligence, her personality was stronger and more open than Léa’s. Her employers had reported that she could be insolent at times. Nonetheless, she was a hard worker and was known as a good cook.

Léa was the shy one. Born in 1911, she was the youngest child of three girls. Evaluations indicated that Léa was of slightly lower intelligence than her sister, and she was introverted, quiet, and obedient. From infancy, Léa grew up with her mother’s brother until he died, and then she went into a religious orphanage until she was 15 years of age.

The Lancelin Home at 6 rue Bruyere

Christine and Léa Papin were now of age to work. In 1926, they were fortunate to land a domestic live-in job together in Le Mans in the home of the Lancelin family: a retired lawyer, his wife, Léonie, and their adult daughter, Geneviève. Christine served as the family cook, while Léa cleaned the house.

The Papin sisters were, by most accounts, good girls and model housemaids. Every Sunday they dressed up and attended church, and they had reputations as being diligent workers with proper behavior. Known to be rather unsocial, Christine and Léa preferred their own company over that of others. Each day, they had a two-hour break after lunch, but instead of going out to enjoy the day, they stayed in their bedroom.

By 1933, the Papin sisters had been with the Lancelins for 6 years. Christine was 27 years old and Léa was 21 years old. On February 2 of that year, Mrs. Lancelin and her daughter arrived home around 5:30 to a mostly dark house. It was the second time in a week that the malfunctioning iron caused the electrical fuse to blow while Christine was ironing. Oddly, the iron had just returned that day from the repairman who said he could find nothing wrong with it. When Christine informed Mrs. Lancelin that the iron broke again, the Madame was angry and a dispute broke out.

Of course, there had been other difficulties in the past; Mrs. Lancelin was a real stickler for a job well done. She would even put on her white gloves to check for dust, regularly gave feedback about Christine’s cooking, and made Léa go back and clean when she missed a spot. But, this time was different.

Crime of the Century

Christine snapped. At the top of the stairs on the first-floor landing, Christine lunged at Geneviève and tore out her eyes with her fingers. Léa quickly joined in the struggle and grabbed Mrs. Lancelin. Christine ordered her to gouge out the Madame’s eyes, then Christine ran downstairs to the kitchen to get a knife and hammer. She proceeded back upstairs where both girls bludgeoned and sliced the mother and daughter. The rabid sisters also used a pewter pitcher that sat on a table at the top of the stairs to bash the heads of the Lancelin ladies. Experts estimate that the incident lasted about 30 minutes. But in the end, the maids had violently slaughtered both women.

Mr. Lancelin and his son-in-law arrived at the home between 6:30 pm and 7:00 pm. The door was bolted from the inside, and the men were unable to enter, although they knew someone was home. The house was completely dark, except for a faint glow coming from the upper level. It seemed highly suspicious, so they went to the police for help.

The Investigation

After entering the house, the police climbed the stairs and found a grizzly scene. Most of the injuries were on the faces and heads of the victims. However, the daughter’s legs and buttocks revealed deep knife lacerations. Both women were horribly unrecognizable, as their faces had been completely demolished. Teeth had scattered about the room, and one of Geneviéve’s eyes lay on the top stair. Investigators later found the other eye under her body. Hidden within the folds of the Madame’s neck scarf were both of her eyes. Madame Lancelin was lying on her back with her legs apart and only one shoe on. Geneviève’s body was facing down. Next to her right hip lay a bloody kitchen knife with a dark handle. Blood covered the entire scene and had even splattered the walls two meters above the bodies.

After police discovered the bodies, they searched the rest of the house. In their minds, they all wondered if the killer had done the same thing to the sisters. But when investigators ascended to the upper level where the maids’ room was, the door was locked. A locksmith went to the scene to unlock the door, and when the police proceeded to open it, they found the girls in bed together with their robes on (some sources say they were nude). Next to the bed on a chair lay the bloody hammer with bits of hair stuck to it. Police asked them what happened, and the sisters immediately confessed to the crime.

Note:

According to Frédéric Chauvaud, author of The Fearful Crime of the Sisters Papin, investigators initially found the victims with their skirts up and their underwear pulled down. During this time in France, it was highly improper to take photos with genitalia exposed, so investigators (perhaps journalists) pulled the ladies’ skirts down to cover their private parts before police finished the investigation.

Arrest and Trial

The police arrested the sisters and they took them into custody. Christine became distressed and exhibited desperate fits when the police separated the girls. Eventually, the authorities allowed a meeting between the sisters, and reportedly, Christine behaved and spoke in a way that implied a sexual relationship.

The court-appointed 3 doctors to administer psychological evaluations to the sisters in order to determine whether or not they were sane. Christine exhibited indifference toward the world and she indicated that she had no attachments except to Léa. The doctors reported that Christine’s affection for her sister was of family devotion and that they did not detect any kind of sexual context within their relationship.

On the other hand, Léa looked up to Christine as a big sister or mother figure. The evaluation came back stating that the sisters had no pathological mental disorders and no family history. The doctors deemed the girls completely sane and indicated that their unusually close union caused the girls to act out together, both equally responsible for the murder.

At the trial, the jurors took only 40 minutes to deliberate. Of course, they found Christine and Léa Papin guilty. Léa received a 10-year prison sentence. Christine was to face the guillotine, although that sentence was commuted to life in prison.

Why Did the Sisters Kill Their Employers?

The brutal double murder enraged the city and shocked all of France. There had never been so much brutality in a murder like this. Many people began to wonder why two girls, who by all accounts were decent girls and had been treated well in their domestic positions, could possess such deep hatred as to commit such an unspeakable crime. The murder itself was heinous, but the gouging out of the eyes with their fingers was an act of animal savagery.

Psychotherapists, philosophers, writers, and others began to chime in with their theories. Some intellectuals sympathized with the girls and could empathize with their class struggle. They saw the crime as a reflection of oppressive class divisions, poor working conditions, and prejudice. Others believed strongly that because the girls had worked in decent employment with a kind family, ate the same meals that the rest of the family ate, and had a generous monthly salary, there was no logical motive for such a crime.

Was it something deeply rooted in the childhood of the sisters? Some sources surmise that the girls were starved of love and affection. But were they? They spent their formative years away from their parents’ instability with family members who supposedly loved them. Although they did eventually have to go to a Catholic orphanage, there is no evidence that they suffered or were not cared for.

The Third Identity

At the trial, a fourth doctor testified. The girls could certainly not be normal. He proposed that the relationship between Christine and Léa was a complete merger of personalities and that Léa had lost her identity to the dominant personality of Christine. In essence, there was no “Christine,” and there was no “Léa.” The killer was really the joint personality of the two – a third identity. Psychotherapists around the world scrambled for a diagnosis.

[blockquote align=”none” author=”Elizabeth Kerri Mahon”]The two sisters seemed to suffer from what is called shared paranoid disorder. This condition tends to occur in small groups or pairs who become isolated from the world. They often lead an intense, inward-looking existence with a paranoid view of the outside world. It is also typical in shared paranoid disorder that one partner dominates the other, and the Papin sisters seem to be a perfect example of this.[/blockquote]

Yet another, more sensational theory emerged. Did Mrs. Lancelin discover that the girls were having an incestuous homosexual relationship? Did she see something not intended for her eyes, and is that why the girls gouged out the eyes with their bare hands?

What Happened to the Sisters?

Without her sister, Christine did not fare well in prison. She exhibited bouts of madness and became severely depressed and despondent, eventually refusing to eat at all. Prison officials transferred her to a mental institution, however, she continued to starve herself until she died in May of 1937.

Léa Papin, on the other hand, demonstrated exemplary behavior and served only 8 years of her 10-year sentence. In 1941 she became a free woman. She lived with her mother in Nantes, France, under an assumed name, and worked in hotel housekeeping. On some accounts, she died in 1982. However, in 2000 while making a film In Search of the Papin Sisters, Claude Ventura claimed to have found Léa living in a hospice center in France. The woman had suffered a stroke and was partially paralyzed and unable to speak. She passed away in 2001.

Inspiration in Murder

The Papin case stirred up a great deal of sentiment in its time and became fodder for a number of literary and cinematic works. Here are just a few:

Movies/Documentaries

- Murderous Maids

- The Horrible Crime of the Papin Sisters, a documentary by Patrick Schmitt & Pauline Verdu

- The Maids, a play by Jean Genet

Literature

- The Papin Sisters (Oxford Studies in Modern European Culture)

- The Murder in Le Mans, an essay in Paris Was Yesterday, a book by Janet Flanner

- The Crime of the Papin Sisters, an essay by Neil Paton (see reference below)

Looking at the Big Picture

In the aftermath of the Lancelin murders, there was a reverberation of thoughts, emotions, and fears. The first stage was shock and outrage. Then the question of “Why did they do it?” Then, the reflection of the bigger picture. Were there things about society, flaws in the social structure, callousness of the religious orphanages, or much too much oppression and persecution, that made them do it? Did society as a whole need to change?

Whether or not the Le Mans double murder resulted in any sort of societal shift in paradigm is uncertain. What is certain though, is that nearly a century later, the northwestern French city is still known for little more than the 24 Hours of Le Mans car race. But even today, the savage murder that took place at 6 rue Bruyére on February 2, 1933, still echoes throughout the land.

You May Also Like:

The Disturbing Crimes of a Father and Son

The Bizarre Story of Little Pauline Pickard

References:

Neil Paton. The Crime of the Papin Sisters.

Patrick Schmitt & Pauline Verdu. The Horrible Crime of the Papin Sisters, published on Youtube by Real Stories, 2016.

Sites accessed June 23, 2017.