In 1726, the hot topic in British society was the news of Mary Toft, an Englishwoman from Goldaming, Surrey, who claimed to be giving birth to rabbits. She had convinced the finest scientists, doctors, and even King George himself in London that she was able to do so. The news was fascinating for the people in London, and the interest was maintained by Mary Toft, who ultimately delivered a number of rabbit babies over the next several months. What are the facts behind this mysterious story?

Early Life of Mary Toft

Mary Toft was born in c.1701, the daughter of Jane Denyer and John Denyer, and grew up a poor and illiterate woman. In 1720 she married Joshua Toft, a journeyman clothier. The couple settled down in Godalming, in Surrey, and had three children: Anne, Mary, and James.

According to the surviving records, Mary Toft became pregnant again with her fourth child in 1726, but suffered a miscarriage that August. However, despite this miscarriage, she still seemed to be pregnant, and went into labor on the 27th September, 1726.

Animal Babies

When Mary Toft went into labor, she was attended by Mary Gil, her neighbor. Later, she was also attended by Ann Toft, her mother-in-law. Mary surprisingly gave birth to something that looked like a lifeless cat. The family quickly sought the help of John Howard, an obstetrician from nearby Guildford, who was initially skeptical about the case and dismissed it.

Mary Toft (James Caulfield (1764–1826) / Public Domain)

However, the very next day, Howard visited Mary Toft, and he was shown the animal part that she had supposedly given birth to the previous night. That following day, John helped in the delivery of additional animal parts. By the next month, Mary also produced a head of a rabbit and the legs of cats. In one day, she gave birth to about nine dead rabbit babies.

The news of the miraculous birth started to spread in London. Howard had sent letters to the renowned scientists and doctors of England, as well as the King’s secretary, to inform them about a human giving birth to rabbit babies.

The Investigation Begins

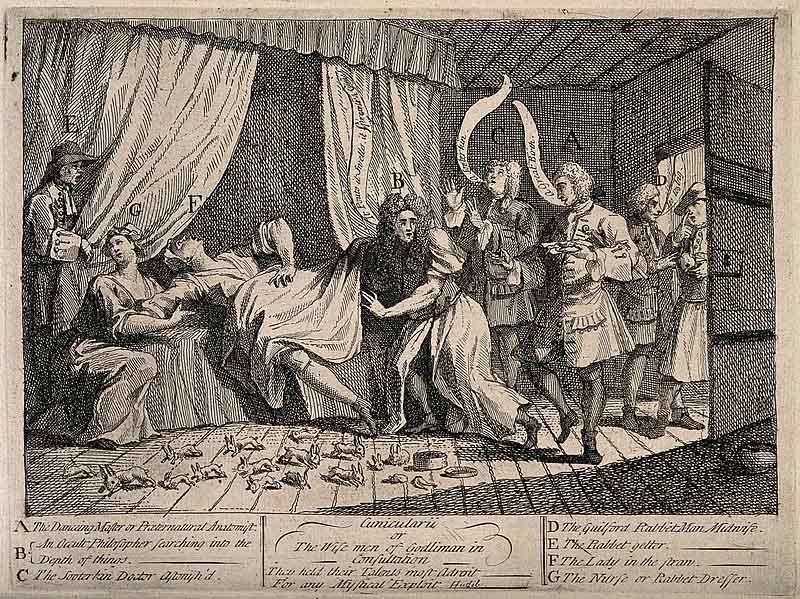

The news of miraculous birth had made the King curious, and he sent two men to investigate the case. These two men were Nathaniel St. André, who was a Swiss surgeon-anatomist, and Samuel Molyneux, the secretary of the Prince of Wales.

The rapid spread of the news had also made Mary Toft a local celebrity. So, she was moved from Godalming to Guildford for close monitoring by John Howard. On the 15th November, 1726, Molyneux and André arrived at Howard’s house in Guildford. On arrival, they received the news that Mary had given birth to her fifteenth rabbit. And with both men present present, Mary delivered yet more dead rabbits.

Nathaniel St. André, the ‘Rabbit Doctor’ (Unknown Author / Public Domain)

The doctor conducted a medical examination of the lungs and other internal organs of the baby rabbits. The results showed that the rabbits didn’t develop in the womb of Mary Toft. However, St. André felt the belly of Mary, and concluded that the rabbits were formed in her fallopian tube. He considered Mary’s case to be a genuine one and took some of the rabbit specimens back to London to present to the King as well as the Prince of Wales.

Further Investigation

However, the investigation did not end here. Owing to the rapid spread of the news, the King sent another man, a German surgeon named Cyriacus Ahlers, along with Mr. Brand, a friend of the King, to further investigate the case in Guildford. Ahlers witnessed several rabbit births and conducted medical examinations of Mary. However, unlike St. André he was not convinced about the births.

When Ahlers examined the rabbit parts back in London, he found hay, corn, and straw in the dung pellets of one rabbit. This was a piece of strong evidence that the rabbits were not developed inside Mary, and on the 21st November, 1726, Ahlers reported to the King that he suspected a hoax.

Sir Richard Manningham, a reputed doctor, and a midwife, was also contacted by St. André to look into the case of Mary Toft. He observed Mary giving birth to the rabbit babies. He also was not convinced, but St. André and Howard convinced him not to disclose his doubts until they found any proof of fraud. It looked as if St. André and Howard were making efforts to save their public reputations.

Mary’s Growing Popularity

In weeks, Mary Toft had become a national sensation. The story gained a lot of press attention. When asked about the strange births, Mary explained that she had been working in the field, and a rabbit had startled her. She, along with another woman, started chasing the rabbit but could not catch it. They later failed in catching another rabbit too.

Mary claimed to have been startled by a rabbit, which later appeared in a dream (Eric Sonstroem / CC BY 2.0)

That same night Mary Toft had a dream in which she saw she was in the field and had both the rabbits in her lap. She suddenly started and woke up from her dream. From that time, Mary had a strong and constant desire to eat rabbits. However, as she was poor, she could not afford it.

Observation and Examination

On the 29th November, 1726, Mary Toft was taken to Lacy’s Bagnio, a bathhouse in the Leicester Fields of London. Under the supervision of St. André, Mary was studied by several eminent surgeons and physicians. John Maubray was one among them. In The Female Physician, John Maubray had proposed that women could give birth to creatures called “sooterkin”.

Being a proponent of what he called “maternal impression”, he believed that what the mother dreams or sees has a significant influence on her conception and pregnancy. According to the reports, John Maubray was quite happy to attend the case of Mary as he saw an opportunity to prove his theories.

Dr. James Douglas, a reputed man-midwife and anatomist, was also invited by St. André to observe the rabbit births of Mary Toft. When Douglas arrived, he found a number of medical men and doctors, who had also been summoned by St. André.

St. André hoped that Douglas would validate the births of the rabbits by Mary Toft. However Douglas was quite convinced that the whole matter was a complete fraud. There were similar disagreements between the other medical men gathered at the bathhouse. While some believed the births to be genuine, others were suspecting a fraud case.

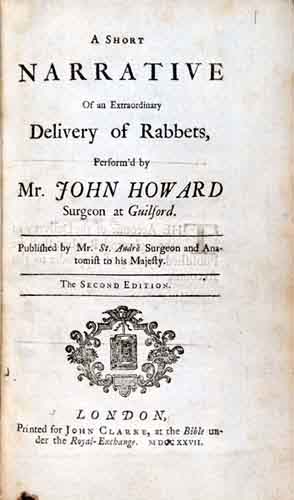

On the 3rd December, 1726, St. André even published an account of the event which he named as “A Short Narrative of an Extraordinary Delivery of Rabbets.” However, Douglas considered the book as merely a collection of impossibilities.

Frontispiece to St. André’s Book (Nathaniel St. André / Public Domain)

The Revelation and the Truth

Things took a sudden turn when Mary did not give birth to any rabbits. However, still, she seemed to go into labor pain. After she suffered a seizure, during which she lost consciousness, Mary was found to be suffering from a serious infection.

She had a severe fever and continued to slip in and out of consciousness. Some considered this a further on-going symptom of her extraordinary condition. But on the 4th December, 1726, the whole mystery seemed to be resolved, when a porter was seen sneaking a rabbit into her room.

Mary Confesses

So, the hoax was finally revealed. Thomas Onslow, a politician and local landowner, had been conducting an investigation and found out that Joshua, the husband of Mary, had been buying young rabbits for the past month. This provided him with sufficient evidence to bring the fraud to light.

He wrote a letter to Sir Hans Sloane, a physician, mentioning that he would publish all his findings soon. On the same day, Mary’s porter also confessed to Manningham and Douglas to taking bribes from Margaret Toft, Mary’s sister-in-law, to procure for her the smallest rabbits he could find. When questioned by Douglas, Margaret confessed only that she had bought the rabbits for eating.

Then, Manningham and Douglas decided to confront Mary and make her confess the truth. They acted quickly and a Justice of the Peace, Sir Thomas Clarges, was called to the bathhouse. Immediately, Clarges took Mary Toft into custody and started questioning her relating to the matter. However, Mary was not willing to confess at all.

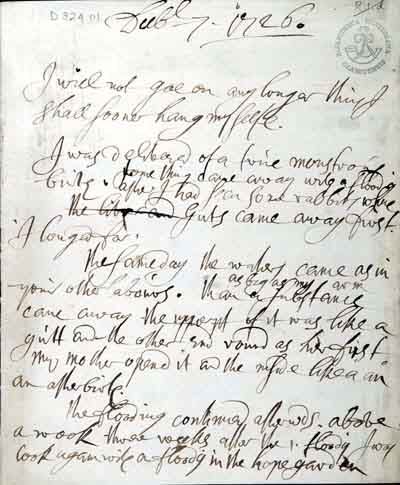

Mary Toft’s confession, taken down by James Douglas (James Douglas / Public Domain)

Douglas questioned Mary for several hours on three to four occasions. Over the next few days, a lot of pressure was put on Mary to confess, but she didn’t. Finally, Mary was threatened by Sir Richard Manningham with painful experimental surgery, in order to find out what was different in her from the other women. Faced with this dangerous choice, Mary finally confessed and admitted the truth on the 7th December, 1726.

Mary Toft confessed that she had manually inserted the dead rabbits inside her and allowed the rabbits to be removed to give people the impression that she was giving birth to the rabbits. Through different confessions, Mary indicated the involvement of a local organ grinder’s wife, her mother-in-law, a mysterious stranger, and John Howard.

Mary Toft’s confession created quite an awkward moment for St. André, as he had published “A Short Narrative of an Extraordinary Delivery of Rabbets” only four days earlier on the 3rd December, 1726. It can be assumed that St. André was not involved in the hoax, but genuinely believed the explanation provided by Mary Toft.

The Aftermath of the Rabbit Hoax

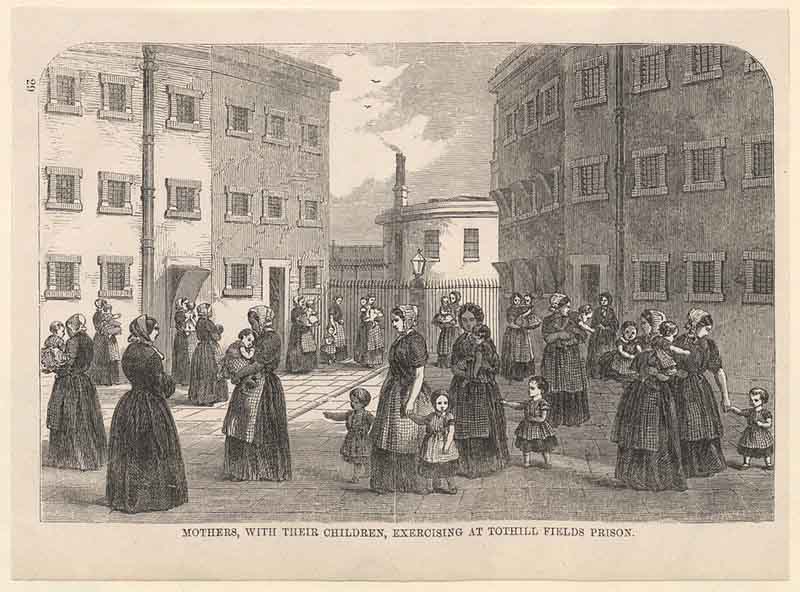

On the 9th December, 1726, less than two and a half months after the first rabbit baby, charges were put against Mary for being a “Notorious and Vile Cheat.” She was then sent to the Bridewell prison and allegedly exhibited in front of a large crowd.

The medical professionals involved in the case also had to face the consequences of the hoax. There was a great deal of public mockery at these medical professionals who were considered highly gullible. The Prince of Wales was also singled out for mockery, and William Hogarth even made fun of the incompetence of the medical professionals in the early 1700s.

Etching of Mary Toft. St. André is figure “A”. (Science Museum Group / CC BY 4.0)

However, by January 1727, the moment had passed and people began to lose interest. James Douglas and Sir Richard Manningham, while having to bear embarrassment to a certain extent, remained secure in their reputations and careers. The reputation of St André however was highly affected. On the 9th December, 1726, he published an advertisement in the “Daily Journal” where he tried to justify his actions, but to no avail. He lost favor in the eyes of the court. Moreover, all his patients left him. He retired from practice and died in poverty in Southampton in 1776 at the goodly age of 96.

John Howard also had to answer a lot of questions relating to the “Cheat and Conspiracy of Mary Toft.” However, ultimately his case was dropped, and he remained a popular figure in Guildford.

What Became of Mary Toft?

According to reports, the crowd mobbed the Tothill Fields Prison, Bridewell, for several months in order to catch a glimpse of the infamous Mary Toft. She also became physically quite ill in this time. Her case was dismissed by the court due to the lack of proper evidence or proof of guilt. However, she remained in jail for several months and was finally discharged only on the 8th April, 1727.

Tothill Fields Prison, Bridewell (Unknown Author / CC BY 4.0)

The Toft family could no longer profit from the matter, and Mary returned to Surrey, where in 1728, she gave birth to another daughter, Elizabeth. Little information is available about the later life of Mary. However, she reappeared in 1740, when she was charged with receiving stolen goods, although later acquitted. She died and was buried in Godalming on the 13th of January, 1763. The obituary columns of the London newspapers made note of her death.

A question that comes to the mind of most people is that what made Mary Toft and her family create the whole rabbit hoax. However, the answer to this question is quite easy. The family saw it as an opportunity to make good moneyand enhance their living standards. It would fascinate both the rich and poor people alike, and Mary would be exhibited for a price. However, the hoax did not become a success in the case of Mary Toft. She could only succeed in becoming an object of curiosity, and nothing more.

Top Image: Source:

By Bipin Dimri