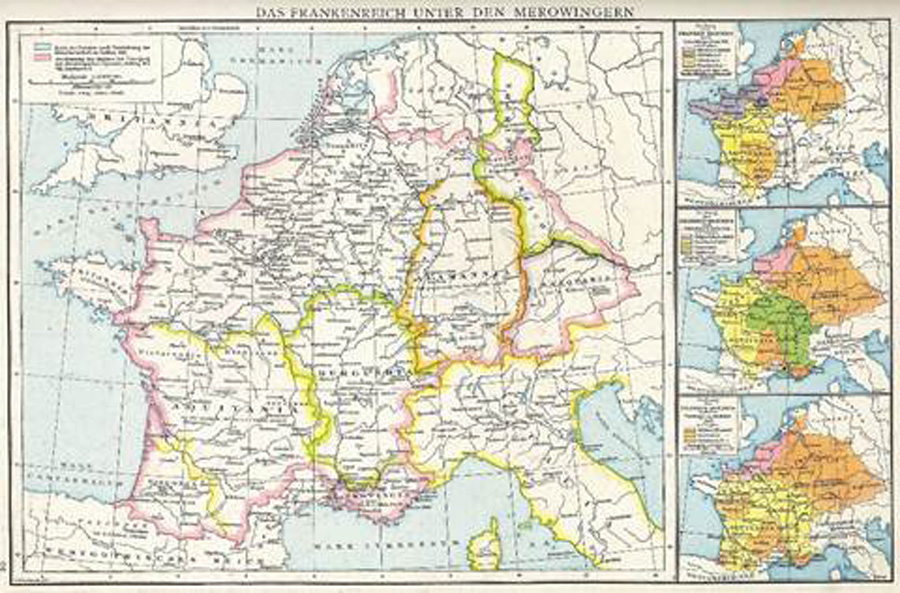

The Merovingian Dynasty was a family of Frankish Kings who ruled during the 5th century AD, a key dynasty of rulers in Dark Age continental Europe. They were often called as the “long-haired kings” owing to their tradition of keeping unshorn hair.

After the Roman Empire collapsed, it was the Merovingians who stepped into the power vacuum, playing an important role in reshaping the political map of Europe and providing stability to the region. They held control for over 250 years, before being usurped and replaced with the Carolingian dynasty.

But there is a curious association with this line of Kings. According to recent popular theories, the Merovingians are identified as the descendants of Jesus Christ, who escaped crucifixion and fled to France with a pregnant Mary Magdalene, settling there.

A Royal line indeed, but is there any truth to the stories? And who were these fierce, Frankish warrior kings?

A Mystical Origin

The Merovingian Dynasty got its name from Merowig or Merovech, a Salian Frank leader from 447 AD to 457 AD. His name was popularized in history when his son, Childeric I, was successful in achieving a number of victories against the surrounding Saxons, Visigoths, and Alemanni. Childeric I carved himself a kingdom and the Merovingian dynasty was born.

At this point Christianity was not associated with the dynasty. According to the 7th century Chronicle of Fredegar, the Merovingian descended from quinotaurs, sea-beasts.

As per the legendary tale, a man named Chlodio, along with his wife, stayed by the sea one summer. When his wife had gone to bathe in the sea one midday, she was found by a beast of Neptune, and fell pregnant. She gave birth to a son, whom she named Merovech.

This tale attributed the Merovingian dynasty with a supernatural origin and gave them the authority to rule. Such stories were often associated with ruling houses, seeking to aggrandize the rulers and cement their position of power.

But the likely truth is more prosaic. According to Flinders Petrie, a British Egyptologist, the Marvingi who lived near the Rhine were actually the ancestors of the Merovingians.

Powerful Rulers

The Merovingian kings were called as long-haired kings as they never used to cut their hair, believing that there was power in long hair. For them, the cutting of the hair of the king was considered a symbolic loss of power. A King who had his hair cut would be forced to step down.

But when in power the king was the master of all the spoils of war, claiming the lands of his defeated opponents as well as people and possessions. It fell to him to redistribute the conquered wealth among his first followers as he saw fit, ensuring loyalty amongst his warriors.

The law of the Merovingians was not universal, instead being applied differently to each man as per his origin. The Frankish kings gave permission to their army to loot and plunder after any battle, bringing all the plunder to a designated spot. Later, the plunder would be divided among the warriors and the king, according to their worth.

A favored target for such pillaging attacks was the Roman Catholic Church. The Church was a valuable target, with much treasure in gold and precious metals. And the Franks were not Christians by religion, leaving the divine protection the Catholics claimed poor protection against a Merovingian attack.

The Merovingian kings used to appoint magnates from among his powerful families to act as “comites.” These nobles were responsible for levying armies for the King from their lands, called “milites.” In return, the King would grant them lands.

National assemblies of the nobles and their armed retainers were held annually, where the major policies were decided, usually about who to attack next. However, unlike their Roman predecessors, these decisions were made for the benefit of the nobles alone.

According to a number of scholars, the Merovingians lacked the sense of responsibility to their citizens that had been seen in the Roman Republic. They were also criticized by several historians for their oversimplified views, where a lack of support for their peasant class undermined their domestic economy.

A Christian Realization

The development of Christianity started among the Merovingians when King Clovis I, the grandson of Merovech, was baptized and became a Christian. Clovis had married a Burgundian woman, Clotilda.

Clotilda was a Roman Catholic and wanted her children to be Christians, rather than the gods of Clovis. Her husband had agreed to this, although he himself continued to remain as a pagan.

But the situation changed during a battle against the Alamanni, a confederation of German tribes. Sensing defeat for the Merovingians, Clovis made a vow that if Clotilda’s God provided him with victory in the battle, he would be baptized and convert to a Christian.

After making his vow, the battle turned in favor of the Merovingian king. The Alamanni leader was killed, and the battle was won by the Franks.

Clovis kept his vow. He was baptized in AD 496 in his capital city by Remigius, the Bishop of Reims, and became a Roman Catholic.

Orthodox Christians

The conversion of Clovis into Christianity had a significant historical impact from a cultural perspective. However, Clovis and his army remained as warlike as ever, still using brutality and treachery in order to defeat the opposing forces in battle.

As loyal Catholics, the Merovingians were powerful allies of the Pope in promoting Catholic Christianity. Even though the Merovingians were barbaric and harsh, their promotion of Catholic Christianity resulted in the spread of Christianity to England.

However, the harsh practices of the Merovingians were often quite detrimental to the Church. The Merovingians often viewed the Church as an income source for their profit. They even appointed laymen as bishops, in order to sell church offices for money. Pope Gregory made an attempt to bring about a reform, which was strongly resisted by the Merovingians.

However the conversion of Clovis was different to that of other Germanic tribes nearby. After converting to Roman Catholicism, Clovis maintained a loyalty to the Nicene Creed, the forerunner of modern Catholic orthodoxy.

While a majority of Germanic people followed Arianism, Clovis and his people accepted the orthodox understanding of Jesus Christ. This set them apart, and may have contributed to later theories regarding their divine heritage

A Divine Line of Kings?

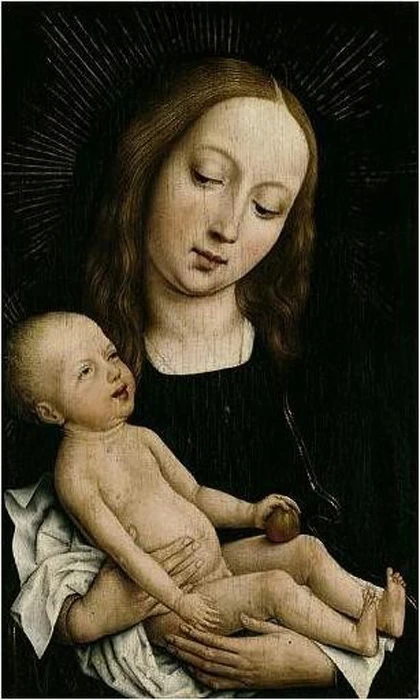

So, where does the theory that they were descended from Jesus come? So the modern theory goes, Jesus escaped death on the cross (being cut down before he died) and was smuggled out of the Middle East by ship, accompanied by a pregnant Mary Magdalene (the “Holy Grail” here being reinterpreted as the “Sang Raal” or royal blood, that is the pregnant Mary).

Arriving in southern France, he established a dynasty there and his children went on to become the Merovingian kings, perhaps unaware of their own divine ancestry. But is there any surviving evidence from the Merovingians themselves to support this?

What contemporary sources relating to the origin as well as the history of the Merovingians survive are very limited. Of the primary sources, such as the Decem Libri Historiarum or the Chronicle of Fredegar, no mention is made of this connection to Christ.

Other than these chronicles, there are capitularies, letters, and more that reveal the history of the Merovingians. They again are silent on this divine lineage.

It seems that the Merovingians, while happy to claim descent from fantastical mythological beasts, did not believe they were divine in a Christian sense. Their early paganism shows that, even if they did descend from Jesus, they had forgotten whatever he taught them.

In books like Dan Brown’s The Da Vinci Code, or Holy Grail, and Holy Blood by Michael Baignet and Richard Leigh, the Merovingian kings are considered to be descendants of Jesus Christ and Mary Magdalene. However, it is without proof. No evidence, either from the Merovingians or any other credible source, supports this fantastical claim.

Top Image: Source: warmtail / Adobe Stock.

By Bipin Dimri