The Moeraki Boulders are huge spherical rocks on Koekohe Beach on the Otago coast of New Zealand’s South Island. Appearing like a congregation of planets, the stones, with their sheer size and nearly perfect shapes, give birth to an alien landscape. Some of them remain partially encased by the surrounding cliffs, while others have completely revealed their beauty with patterned surface lines and colorful hollow cores. Maori legends provide one explanation of the boulders’ creation, while science proposes others. However, the awesomeness of these giant stones persists, and these geological mysteries of creation leave many people wondering exactly what they are and how they formed.

Moeraki Boulders on the beach in New Zealand. Source: Wikimedia, Pseudopanax, public domain.

Concretions of Beauty

People sometimes mistake the Moeraki Boulders for dinosaur eggs, alien remnants, or evidence of giants. Although their massive size and odd surface patterns are unique, round stones in nature are quite common. These are known as types of concretions which are mineral-cemented masses that often form within layers of sediment. The word ‘concretion’ comes from two Latin words. Crescere, means ‘to grow,’ and con, means ‘together.’ Hence, the stones are giant balls of sediments that have grown together over time in a process of cementation.

Most of the Otago concretions are round – some of them almost perfectly – while others are more ovoid or slightly irregular in shape. They range in size from about 1.5 meters to a little over 2 meters. Variably, they lie clumped in groups or as individuals scattered across the beach.

A number of the spheres are cracked and display a turtle-like mosaic.

The cracked surface of this Moeraki Boulder creates a geometric or turtle-back design. Source: Pixabay, public domain.

Maori Legend

Before scientific inquiry, humans viewed the world and nature from a magical and wondrous perspective. Questions about the universe sparked colorful myths and legends that are still intriguing even today, and the Maori legend about the stones on the Otago Coast is no exception. One version of the story tells that long ago, the Kähui Tipua people sailed out on an expedition to the mythical land of Hawaiiki in their double-hulled waka (canoe) called the Arai Te Uru. Their goal was to find and bring back kumara sweet potato plants to grow back home.

A storm engulfed the Arai Te Uru during the return journey and the hulled voyager wrecked off the Otago Coast at a place called Shag Point. The hull of the canoe magically became a reef near the Waihemo River Mouth. Baskets and gourds that had carried eels and water also washed ashore, preserving the cargo for all time as the giant boulders along the Otago Coast of South Island. (New Zealand Department of Conservation).

How Were the Moeraki Boulders Formed?

According to scientists, the formation of these concretions began approximately 60 million years ago within the muddy Paleocene marine sediments of the Moeraki Formation. Each concretion began with an organic nucleus, “such as a leaf, cone, shell, fish-bone, or other relic of plant or animal” (Geikie:96). Sedimentary particles and minerals, such as calcite, aggregated around the organic matter in concentric layers (layer upon layer). The process is similar to the way a natural pearl forms around a foreign particle within an oyster. In a complex chemical process, the minerals cemented the particles together. The process continued and the concretions grew slowly over millions of years.

How Do Concretions Become Round?

Not all concretions are round, although many of them that form in layers of sediment tend to be spherical. However, the scientific community is still debating the exact process that results in this smooth round shape. Proposals include tide action (rolling and wearing down), gravity, or factors of sedimentary pressure. The most accepted theory proposes that the equal availability of minerals in a liquid solution from all directions surrounding a nucleus allows for equal formation.

It may be that the Moeraki Boulders formed within sediment that was soft enough to allow mineral-rich water to flow through the muddy particles. Minerals began to precipitate around some nucleus, perhaps of an organic nature. Without resistance or lack of material from any one direction, the concretions were able to form equally and nearly perfectly from each directional point.

What Caused the Cracks?

Sometime after the concretions formed, cracks called septaria began to occur. These fractures on the outer layers have subsequently become filled with yellow and brown calcite, quartz, and dolomite deposits in a process known as secretion. The occurrence of septaria is a rather mysterious process and scientists are not exactly sure what causes them. However, theories include:

- Drying out of the concretion

- Shrinkage of the cores

- Gases that expand when the organic centers decompose

- Earthquakes or compaction that caused fractures

Interestingly, the large stones are hardest at their outermost layers which are comprised of roughly 20 percent calcite. Inside some of the crumbling stones, the centers are hollow, perhaps having decomposed over time.

How Did the Boulders Get on the Beach?

The largest of the spheres took up to 5 million years to grow to their fullest form. Having cemented with minerals, these concretions became significantly harder than the sediment surrounding them. Subsequently, Geologic activity caused an uplifting of the mudstone out of the sea to create the cliffs along the beach. Within the many meters of sediment, the boulders remained encased. Over time, wave action eroded away the softer sediments to reveal the giant stones. Each time the ocean excavates a new boulder, the newly exposed concretion rolls down onto the beach to join the others. Today, the shoreline is artfully arrayed with spheres that were preserved because of calcification that resisted erosion.

A shattered Moeraki Boulder reveals a colorful core. Source: Wikimedia, Oren Rosen.

Early Documentation

Maori ancestors occupied the vicinity of the Otago Coast for hundreds of years, beginning around the 13th century CE. However, documentation of the Moeraki Boulders did not take place until European involvement. Hence, it wasn’t until around 1814 during the War of the Shirt that the world learned of the unique spheres.

The Mysteries of New Zealand’s Kaimanawa Wall

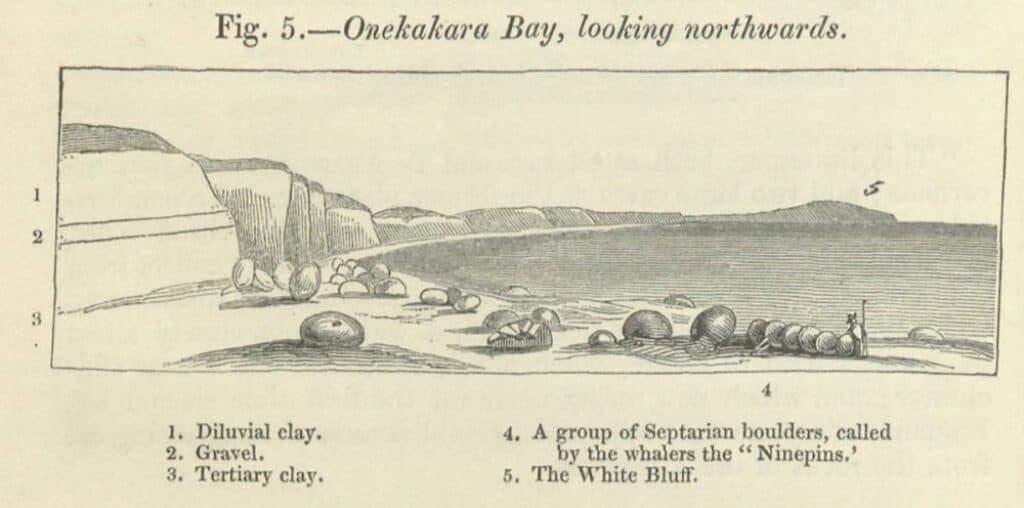

Walter Mantell was a politician and scientist of geology and paleontology. As part of his work, he documented the concretions in a seaside sketch dated to 1848. In it, Mantell showed the presence of a greater number of beach stones than there is today.

Mantell’s father, Gideon Mantell (1790-1852), was also a geologist and paleontologist. His work on Iguanodon had a significant influence on the study of dinosaurs. In 1850 he published a book, Notice of the Remains of the Dinornis and other Birds…, in which he includes the following observations that Walter made while working on the Otago Coast.

“Midway between the Bluff and Moeraki, the clay contains layers of septaria [concretions], varying from one to five feet and more in diameter. Hundreds of these nodules, which had been washed out of the undermined clay cliffs by the encroachment of the sea, were scattered along the beach, as represented in the sketch, fig. 5. Some were subglobular,

[Quote continues…] 1850.] MANTELL ON THE GEOLOGY OF NEW ZEALAND.

others spherical; many were entire, whilst others were broken, and glittering with yellow and brown crystals of calcareous spar.”

Foggy day on the Koekohe beach. Source: Wikimedia, pseudopanax, public domain.

Other Concretions Around the World

-

Public dom. Tramp

Koutu – Hokianga District, North Island, New Zealand. Although the concretions at this site are very similar to the ones on the Otago Coast, the Koutu site has even larger examples, ranging up to 5 meters. Fossilized animals have been found within some of the nucleus cores of the concretions. In 2013, scientists found a Late Cretaceous shark vertebrae in an outcropping of boulders at Koutu.

-

Flickr John Fowler

Bowling Ball Beach – Schooner Gulch State Beach, California, USA, north of Gualala. Along Highway 1, there is a hidden beach that contains a high density of concretions. From the parking lot, visitors must take a short trek with some minor scrambling around rocks and down a makeshift ladder to get to the beach. Like the Moeraki Boulders, these are also spherical cannonball concretions.

-

CC Alex Babkin

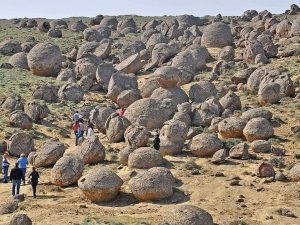

Valley of Balls – Torysh, Mangystau Province, Western Kazakhstan. This steppe site is near the town of Shetpe. It is home to gigantic round and irregular concretions averaging 3-4 meters in diameter. Unlike the Otago Coast boulders, these stones formed within layers of volcanic ash in a process that scientists are still trying to understand.

Caring for the Moeraki Boulders

The local Maori culture values a connection with nature and the preservation of its resources. Thus, the Moeraki fishing village oversees the care for its stone-dotted beach, which is constantly undergoing change and erosion. The stones themselves are decomposing and cracking, and a number of them now lie in shattered pieces across the beach. However, the region welcomes visitors who are always eager to catch a glimpse of the natural wonders. Tourists can walk the beach to get a close-up view. For those who don’t want to get their feet sandy, there is also a viewing platform overlooking the area. From that vantage point, visitors can see the 60 million-year-old spheres that all began with a simple organic particle in the muddy seabed. Additionally, viewers can observe Hector’s dolphins cavorting in the sea, oblivious to the legendary splendors lying on the beach.

You May Also Like:

The Pobiti Kamani Stone Forest of Bulgaria

Mysteries in the Plain of Jars, Laos

References:

Geikie, Archibald. Textbook of Geology. Macmillan, 1882.