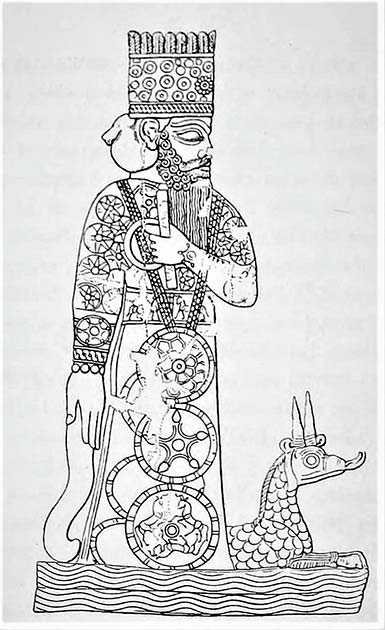

Mušḫuššu is, according to Babylonian myths, a dragon with a very thin and scaly body. It had an extended neck, a long tail, lion-like arms, and an eagle’s legs. To make this creature more intimidating, it had horns, ears, and eventually wings as well.

One of the first mythical creatures, it has a long history in Mesopotamian mythology and left its mark in history for other cultures to pick up. Could we be looking here at the original dragon?

What was Mušḫuššu?

Mušḫuššu, also known as the Mesopotamian dragon, is a symbol of the ancient Mesopotamian hero-deity Marduk. It was prevalent, particularly after victories of the Babylonian kingdom.

Marduk was the offspring of Enki and Damgalnunna, the two primordial deities of the Mesopotamian religion. They created the Earth.

The first appearance in literature and archaeology shows Marduk in the Mesopotamian myth ‘the legend of the Enuma Elish’. In this particular story, Marduk defeats the dangerous Mušḫuššu and makes it his servant. It is an iconic and ultimate triumph for Marduk with Mušḫuššu also becoming known as the Marduk Dragon.

Mušḫuššu, along with other sacred animals, is a favorable and prevalent iconography of Mesopotamian culture. The animals have been seen as protection from enemies, protection from the gods, and for divine, good luck.

Thus, it is no surprise that one place where Mušḫuššu can be seen is on the Great Ishtar Gate. Some of the remnants can be seen today in Berlin, Germany at the Pergamon Museum.

- (List) Mother of Monsters: The Eleven Children of Tiamat

- Ugallu: Lion Headed God-Monster of Babylonian Life Insurance

The Ishtar Gate is one of the gates surrounding a much larger city structure. It was said to have been built in 575 by King Nebuchadnezzar II in order to encircle and protect the city of Babylon.

Not only did this add to the protection of the city, but it also added to the magnificence of the city and its legendary status. Part of the most extraordinary aspect of the Ishtar Gate can be found at the base of it. It is covered in figures of bulls, lions, plants, and the Mušḫuššu Dragon.

Dragons in Mesopotamia and Other Cultures

Mušḫuššu dragons and Babylon: It is clear that Mušḫuššu held a special place in Babylonian culture and the creation mythology. In Babylonian myths, Tiamat the primordial goddess of water, is the mother of dragon monsters which makes it the mother of Mušḫuššu, Tiamat.

Three of these dragons hold high-dignity titles. Musmahhu, Basmu and Usumgallu. The legends claim that these dragons or Mušḫuššus were three-horned and were slain by the Sumerian deity of farming, Ninturna. Thus, it has been suggested that these dragons were the inspiration for the Ancient Greek three-headed dog, Cerberus.

Many Mesopotamian and Babylonian monsters were also seen in constellations. One of the most famous ones, and the earliest ones, was the constellation Basmu. In Ancient Greece, this constellation was interpreted as the Hydra. When this constellation is seen, it can look as if a snake, fish, lion, and eagle are all joined together.

For Mesopotamian people, the dragon was a sign of a snake demon or a snake god because of their hybrid features that were mixed across a variety of animals. This is how the myths were propagated and developed. For example, Tishpak, the adversary and opposition of Mardok was often depicted as a slender snake dragon.

The Kalbu Myth or Labbu Myth is thought to be a precursor to the Enuma Elish Legend. The Kalbu Myth is a creation myth for the cosmos and all nature.

Scholars believe that Kalbu is the original version of Tiamat, the mother of Mušḫuššu. In a later version of the same myth, Kalbu is created by Enlil, the God of wind. Enlil created Labbu in order to destroy humans because they disturbed his sleep.

- The Epic of Gilgamesh: Mankind’s First Story?

- Uruk, the First Great City: A Leap Forward for Humankind?

The other gods were so terrified by Labbu that they begged the God of Chaos, Tishpak, to defeat it The legend claims that this took three years for Labbu to bleed out after Tishpak had attacked him. It has been noted that Labbu and Marduk are very similar. Thus it is not surprising that the Marduk Dragon, Mushussu, has become a symbol of the deity Tishpak as he was the opposite of Labbu.

Similar Myths

In the Vedas, a collection of Sanskrit poems, there exists a similar monster of myth known as Vritra. It was a Snake Dragon that represented times of drought. Researchers have often pointed to the fact that Mushussu was created by a Water God in Tiamat and in a nearby culture, snake-like dragons represented droughts.

Vritra is presented as an Asura. This is a specific type of demigod or titan that is always hungry. It is often recorded as being power-hungry, selfish, and cruel. In legend, Vritra is defeated by Indra, the Hindu god of Heaven and leader of all other gods. The story bears a remarkable resemblance to Tishpak defeating Labbu.

Dragons have been seen in cultures all around the world. One place they have been significant is China. The best-known symbol of the emperor has been the dragon who breathed fire. In Ancient China, it was believed that dragons were responsible for many natural disasters such as harsh weather and earthquakes. Even in China today, the dragon still features in the calendar and makes an appearance during New Year festivities.

The main dragon of China has been named as Nien. At the end of every year, legend would have it that Nien would terrorize the local villages. In order to prevent this, the villagers would make loud noises, wear flashy costumes, and use bright lights as well as fireworks. It is this tradition that has continued today.

Dragons were not limited to the East though. The Scandinavian Vikings utilized the symbol of the dragon. Many Viking ships were decorated with a dragon’s head at the stem of the hull. The ships with this symbol were called Drakkar (the Dragon Ships). It is likely that this stemmed from their own creation myths which featured the Midgard serpent, Jormungandar, who surrounded the Earth.

Top Image: Mušḫuššu, representing the god Marduk, on the Ishtar Gate of Babylon. Source: Osama Shukir Muhammed Amin / CC BY-SA 4.0.

By Kurt Readman