This article contains spoilers for the 2019 film Midsommar.

Human civilization has a long and gruesome history of human sacrifice. As barbaric as human sacrifice is now, the practice was common since prehistoric times.

By the Iron Age, around the first millennium BC, religions became increasingly developed and sophisticated and human sacrifice began to happen less frequently in many different cultures. Amongst the Germanic peoples who practiced the Old Norse religion, for example, the practice of human sacrifice was seldom performed.

Yet one of Sweden’s many sagas mentions a rather strange form of human sacrifice. The practice, known as Ättestupa is a form of senicide that has even appeared in the film Midsommar in 2019. What is Ättestupa?

Ättestupa

Ättestupa is Swedish for “kin/clan precipice,” It is a name given to several precipices across Sweden. Ättestupa is also the name of Swedish ritualistic senicide that was said to take place during the pagan prehistoric Nordic times.

The ritual of Ättestupa requires elderly people to throw themselves or be thrown off the edge of a cliff to their death. Swedish legend indicates that Ättestupa took place when elderly people were no longer able to assist in the household or support themselves. It was a way to remove burdens from a clan or family, and the ages at which Ättestupa would occur varied by person.

Senicide or geronticide is the deliberate killing of the elderly or abandoning them to their death. The Hippocratic Oath, developed in the 4th century BC, speaks of human euthanasia with the line, “I will not give a fatal draught to anyone if I am asked, nor will I suggest any such thing.”

The practice of senicide can be found elsewhere in the history of certain cultures and it is suggested that it is associated with periods of hardship. During times of famine, Inuit people would leave their elderly on the ice to freeze to death.

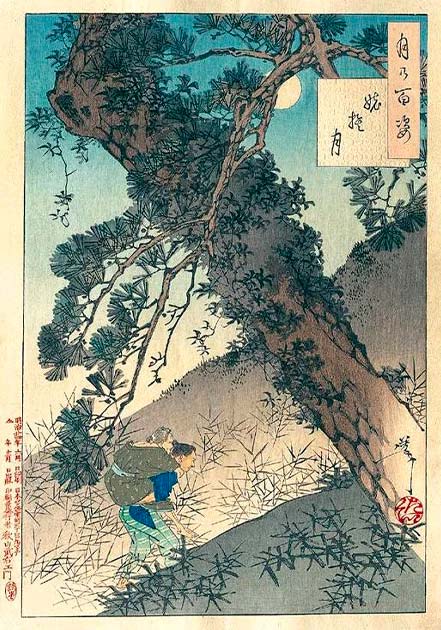

In Japan, there was the practice of Ubasute which means “abandoning an old woman”. Ubasute required an elderly or infirm relative to be carried to a mountain or some remote and desolate place like a forest and left there to die.

This is not all ancient history, either. In Tamil Nadu, the illegal act of senicide known as thalaikoothal is said to occur many times each year.

- The Tophet: Was Ancient Carthage Driven to Child Sacrifice?

- An Ancient Party? The History of Celebrating Midsummer

There is also the still-controversial practice of assisted suicide or physician-assisted suicide (PAS), in which a physician or healthcare worker assists in the suicide of another person. This is legal in many countries under certain circumstances.

In most of the countries where PAS is legal, a person will only qualify for the service if they meet specific criteria, such as having a terminal illness, repeatedly expressing the wish to die, etc. We usually hear of PAS when it comes to younger people, but it is available to the elderly as well.

Instead of jumping off a cliff like the ritual of Ättestupa, voluntary euthanasia commonly involves taking lethal doses of medications like Secobarbital. While senicide is no longer a cultural practice in many places, PAS can be considered another way to end the life of the elderly with their consent.

History of Ättestupa

The term Ättestupa in Sweden first appeared in the 17th century and appears to come from an old Icelandic saga known as the Gautreks Saga. The saga is partially set in Sweden, and the particular story Ättestupa comes from is called Dalafíflaþáttr. The translation of the title is “The Story of the Fools from the Valley.”

In this story, a family is so parsimonious that they would rather kill themselves than see their fortune spent on hospitality and others. The members of this miserly family take turns killing themselves by jumping off a high cliff called Ættarstapi or Ætternisstapi, which means “dynasty precipice.” People began calling high cliffs Ättestupa as a nod to the ritual senicide from the region.

Some former Ättestupa locations in Sweden are Keillers Park in Götenborg, the precipices at Vargön located close to lake Virstulven in Västergö, and the Kullberget in Hällefors in the municipality of Örebro Iän is called “ättestupan” by locals.

Most recently, the 2019 movie Midsommar by Ari Aster includes a scene in which the elderly members of the cult commit ritual suicide by throwing themselves off a tall precipice at the age of 72. This graphic and disturbing scene brought the act of Ättestupa into the vocabularies of non-Swedes who watched the film.

The Truth

Today, Ättestupa is considered by historians and linguists to be a myth. Thankfully the practice or ritual of suicide precipices for the elderly never existed.

Many of the places mentioned in the Gautreks Saga exist in Sweden today, and it is easy to see how the myth and the story about Ättestupa may be believed to have existed as well. But it should be remembered that the lesson of Gautreks Saga is that the family is acting so poorly that they would rather die than share their wealth: the saga is a critique.

This is not to say that senicide never took place during Sweden’s long history. Ättestupa as a ritual never happened, but senicide was common in prehistoric times in the form of abandonment. In Sweden, the word Ättestupa is often used as a political buzzword to describe the poorly funded and neglectful social security programs for retirees.

- The Detroit Occult Murders: What Happened to Benny Evangelista?

- “Thou Shalt Not Suffer a Witch to Live”: The Witch-Cult Hypothesis

Regarding the Ättestupa shown in the film Midsommar, it is essential to remember that while some of the traditional Midsommar practices, like picking flowers, dancing around a maypole, and intergenerational celebrations, are accurate, most of the movie, including the Ättestupa ritual, is inaccurate.

The director Ari Aster admitted to taking great liberties from Nordic folklore, developed a “fake” language that is not Swedish, and even created runestones that are not found in Sweden. Before being hired to write the script of a horror movie centered on midsummer celebrations, Aster had never been to Sweden.

COVID-19

However, recent events have brought the concept, if not the ritual, back into the limelight. During the COVID-19 pandemic, Sweden had looser regulations regarding prevention of the spread of the disease than many other countries across the globe.

The lack of enforcement of wearing masks, social distancing, and looseness of quarantine measures is seen as the government attempting to solve the issue of the pandemic through herd immunity. Herd immunity is the “idea that natural immunity should be built up in the population by either slow or fast spread of infection in order to protect society at large”.

What this herd immunity meant in effect is that the elderly and vulnerable members of society would, in essence, be sacrificed for the good of society as a whole. Ättestupa in reality, albeit in a more modern and less visibly disturbing way.

The Swedish Public Health Administration denied that they were using herd immunity as a form of Ättestupa and has said that the goal was to protect the elderly and infirm. If an old person did not want to catch the virus and die, it was their “individual responsibility” to avoid infection.

It should also be remembered that the two concepts have marked differences. The concept of Ättestupa involves targeted removal of those who do not contribute to society and are therefore a burden, whereas the Swedish COVID-19 policy was an attempt to introduce a natural resistance to the virus with the understanding that those with weaker immune systems would be at more risk.

Sweden was careful to emphasize these risks and attempt to protect as many as possible. The recommended individual responsibility actions included staying away from family members, friends, and caretakers, grocery shopping, or any other measures appropriate to avoid infection.

But the reality, in Sweden and many other countries, was that long-term care facilities and nursing homes have become the new cliffs of Ättestupa. The quality of care for individuals in nursing homes and long-term care facilities is notoriously poor.

Preventable infections and viruses frequently take hold of these facilities exposing everyone to illnesses that can be fatal. In Sweden, face masks were not required or recommended, and it was believed that their public transportation systems were “less crowded” than in any other country.

Working from home was recommended if possible, but it was not enforced. This meant that nurses, housekeepers, and even cooks at these facilities could bring COVID-19 with them to work, exposing high-risk individuals to a deadly disease.

Top Image: While Ättestupa is known from an Icelandic saga, it is not believed that it was performed as a ritual. Source: Captblack76 / Adobe Stock.