Have you heard the story of the angry deity and the flood? The one where the world is flooded but one clever man builds a boat and survives, and then he and his wife then repopulate the sodden planet?

Of course, you have, but it might surprise you to discover we’re not talking about Noah. There are a surprising amount of apocalyptic stories from around the planet that tell almost the exact same story.

One of the oldest is the Greek Flood Myth which tells how an angry Zeus flooded the earth, but the pious Deucalion and his wife survived. It might sound a little familiar.

But the real mystery is why this is. Are these legends borrowing from each other, all descended from some proto-myth about a cataclysmic flood? Or is there something in humanity’s earliest memories about such an event, something which has been told and retold by every culture it touched since?

Ancient Greece’s Answer to Noah

There are various accounts of the Great Greek Flood and Deucalion. Some of them are quite similar with only minor variations, while others are wildly different.

For the most part, we’ll be going with Ovid’s (a Roman poet) version of the story with some Apollodorus (a first or second century AD mythographer) thrown in. These versions include the most common aspects of the Greek Flood Myth.

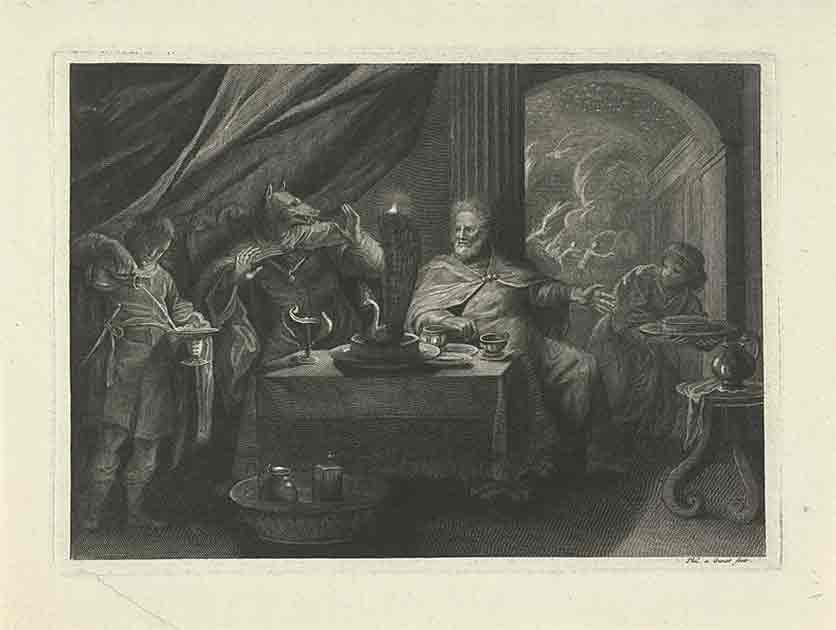

In Ovid’s Metamorphoses, the tale begins with Zeus hearing of all the immoral goings on happening on Earth. He decides to take a look for himself and visits the house of Lycaon, king of Arcadia. The king of the gods is welcomed by the city’s devout residents and Lycaon prepares a grand feast in his honor.

Things take a turn, however, when Zeus discovers that Lycaon plans on tricking him. Lycaon kills and cooks his son, Nyctimus, and serves him to Zeus at the feast, hoping to test how all-knowing the god really is. Zeus is not fooled, being a god after all, and doesn’t appreciate being tested by a mortal king.

The outraged god returns to Olympus where he gathers the council of gods. A decision has been reached: Lycaon has sealed humanity’s fate.

Zeus judges mankind as a whole is as evil as Lycaon and must be eradicated. His first act is to send one of his infamous thunderbolts hurtling at Lycaon’s palace, blowing up his sinful sons and turning Lycaon himself into a wolf. His next act is a bit wider in scope: Zeus’s follow-up is to wipe out the entire Bronze Age with a massive flood, washing away the evil world of man.

This is where Deucalion, usually portrayed as the son of the Titan Prometheus (who gave mankind fire) comes in. Prometheus once again goes against Zeus, this time by warning his son of the flood.

He instructs Deucalion to build a large chest, in reality a giant boat. This is described by the ancient Greek scholar Apollodorus as being, “a chest of the following fashion: to make it fifty cubits long, fourteen wide, and eight high.”

Deucalion and his cousin (or sometimes wife) Pyrrha, then board the boat. They get on board in the nick of time as Zeus begins to flood the earth, covering the land in water and killing every living thing. Every living thing except Deucalion and Pyrrha that is.

Eventually, Zeus notices the still-breathing couple, but seeing their piety decides to spare them. He sends in the North Wind to scatter the clouds and calm the storm. The couple then gives their thanks to the (kind of) merciful Zeus and the flood waters start to subside.

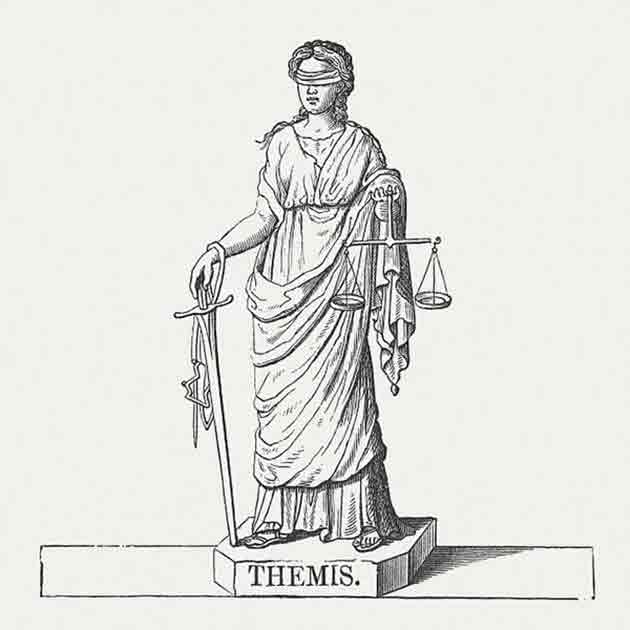

It takes nine days but eventually, the waters drop to the point where Deucalion and Pyrrha can land their chest on Mt. Parnassus (or sometimes Mt Etna, Mt Athos, or Mount Othrys depending on the version). It is only then they realize they are the only surviving mortals and they head to the springs of Cephius to visit the temple of Themis.

Themis was a titaness and a goddess of divine law, order, and custom who commonly played a significant role in the divine order of the cosmos. As such, the couple thought she was the best being to ask for help when it came to repopulating the earth. Themis was happy to help but her answer was somewhat cryptic.

Themis responded, “Leave the temple and with veiled heads and loosened clothes throw behind you the bones of your great mother.” After some deliberation Deucalion and his wife realized that Themis was referring to Mother Earth and the bones in her message were rocks. As they walked away from the temple, they threw rocks and stones behind them.

These stones then began to transform into a new race of humans, but humans crafted in a different fashion, humans with no prior relationship to the gods. As they did this, animals also began to be spontaneously formed from the soil. Thanks to the two humans, life was returning to the earth.

Deucalion and Pyrrha spent some time traveling and finally ended up in Thessaly. Upon their arrival, they got back to making human beings the old-fashioned way, without the need for stones. They had two sons, Hellen and Amphictyon.

Hellen’s offspring were particularly influential. His son Aeolus founded the Aeolians while his second son Dorus founded the Dorians. Both would go on to be extremely significant Greek peoples.

His third son, Xuthus, had Achaeus who founded the Achaeans, and Ion who founded the Ionians. Amphictyon on the other hand succeeded his father as king of Thessaly and founded the Amphictyonic League, a religious and political association of Greek city-states.

Deja Vu

This might all sound more than a little familiar and there’s no wonder. The Greek Flood myth isn’t the only ancient religious story to feature an Apocalyptic flood. In particular, the Mesopotamian Epic of Gilgamesh (one of the oldest surviving recorded tales in history) and the Biblical narrative of Noah’s Ark share some startling similarities with the tale.

All three stories feature mankind being wiped out by a powerful deity as punishment for its perceived transgressions. In the Epic of Gilgamesh, the gods wipe out earth due to human corruption but command Utnapishtim, a wise and pious man, to build a boat and survive the deluge.

- The Epic of Gilgamesh: Mankind’s First Story?

- More than Greek Myth? Sardinia and the Nuragic Civilization

In the story of Noah, which appears in Genesis, God likewise decides to wipe out mankind but commands Noah to build an ark. The three tales then all have the human survivors rapidly repopulating the earth, using some magical smudging of details to avoid the sticky question of mass inbreeding.

While details differ from story to story the general outline is pretty much the same. In fact, the myths are so similar some Second Temple Jewish and early Christian theologians believed that Noah, Deucalion, and Utnapishtim were one and the same and the stories all told of an ancient flood that had hit the Mediterranean region at some point.

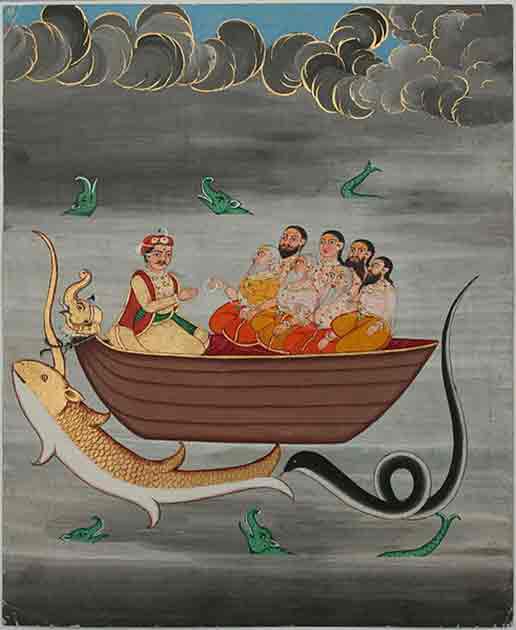

Interestingly, the parallels between the Greek flood myth and other ancient flood stories stretch far beyond the Mediterranean region. Hindu tradition also contains a flood narrative with striking similarities.

In the Hindu epic, the Mahabharata, there is an account of a global deluge known as the story of Manu (or Matsya). Like Deucalion, Manu is forewarned about the impending flood and instructed to build a large boat to preserve the seeds of life. As the waters rise, Manu’s boat comes to rest on a mountain, similar to the way Deucalion’s ark lands on Mount Parnassus.

Likewise, the Native American Hopi tribe has similar flood myths featuring themes of divine displeasure, survival in vessels, and the subsequent repopulation of the Earth. These similarities suggest a shared cultural motif, emphasizing the universality of such narratives in explaining the origins and challenges of humanity.

How can such diverse civilizations feature such incredibly similar stories? Is it evidence that there really was a Great Flood? After all, there’s a point where coincidence can become too implausible.

Well, for a long time, people have done their best to try and prove religious tales true. For example, some believe that Noah’s Ark rests on Mount Ararat in Turkey. Many have claimed that “boat-shaped” formations on the mountain are evidence of the Ark, but these claims have never been substantiated by credible archaeological or scientific evidence.

The truth is that there is no hard archaeological evidence that a great flood once wiped out much of mankind. We know that massive floods did hit ancient civilizations.

The Black Sea Deluge of around 5600 BC featured a dramatic rise in sea levels that may have inspired such stories. Similarly, the Tigris and Euphrates rivers in Mesopotamia often flooded and may have inspired the region’s flood myths. Pretty much everywhere floods.

These parallels between these stories likely suggest a shared cultural consciousness or common source of inspiration, reflecting the human inclination to explain natural disasters like floods and moral lessons through mythology. Like most other myths the Greek Flood myth, and flood myths in general, are just a way for people to explain the seemingly unexplainable.

Top Image: Deucalion, like Noah, survived the great flood by constructing a wooden boat. Source: Aleksander / Adobe Stock.