Scholars continue to debate the existence of King Arthur as a real historical figure or simply folklore. Did an English King unite Britain’s islands against the Saxon invaders or was the legend created to muster up much-needed morale? Let’s examine what the historical record tells us.

Grave at Glastonbury Abbey

In 1191, monks at Glastonbury Abbey in southern England made a most fortuitous discovery in their monastic cemetery – the grave of King Arthur and Queen Guinevere. Contemporary historian Gerald of Wales recorded the find just two years later in his handbook for rulers, the Liber de Principis Instructione:

In our own lifetime Arthur’s body was discovered at Glastonbury, although the legends had always encouraged us to believe that there was something otherworldly about his ending, that he had resisted death and had been spirited away to some far-distant spot. The body was hidden deep in the earth in a hollowed-out oak bole and between two stone pyramids which had been set up long ago in the churchyard there… Beneath it, and not on top, as would be the custom nowadays, there was a stone slab, with a leaden cross attached to its underside. I have seen this cross myself and… the inscription read as follows:

HERE IN THE ISLE OF AVALON LIES BURIED THE RENOWNED KING ARTHUR, WITH GUINEVERE, HIS SECOND WIFE

Gerald of Wales

The monks did not doubt that Arthur was a real king. A leader whose deeds and faith had made him legendary centuries before they happened upon his grave. The discovery was an exceptionally lucky find for them, as the Abbey was in desperate need of funds for repairs. Finding the tomb of Britain’s greatest king was a boon, leading hordes of pilgrims, and their donations, to the impoverished Abbey. As it turns out, the grave was a fake; is this an apt metaphor for the whole of Arthurian history? Was King Arthur real?

Questioning King Arthur’s Existence

Unlike the monks, historians have long debated whether King Arthur was a myth or reality. While no direct evidence of Arthur as a king or a warrior survives today, many historians are hesitant to wholly discredit the possibility that Arthur was a historical figure.

Historians like David Dumville, Nicholas Higham, Guy Halsall, and Michael Wood, while appreciative of the later medieval fictions and legendary impact of Arthur in courtly society, have asserted that a real Arthur, wholly lacking direct and contemporary evidence, did not exist.

Others, like Eric John, in his 1996 Reassessing Anglo-Saxon England, will not dismiss the core of historical reality behind this tradition:

“Only a romantic novelist would seek to find the real Arthur. But traditions of some antiquity say he was a real person and in sufficient number to make it difficult to explain them away. They never call him king but present him as a successful general. They say he won battles in places they name and there is general agreement where those places were. None of this, sounds like myth.”

Historical Context

If Arthur were a real person, he would have flourished in the tumultuous fifth century. An era popularly, but wrongly, known as the dark ages. The Romans had fled Britannia as their Empire diminished, leaving Romanized Britons to the mercy of Saxon invaders. This period swirls with controversy, and historical debate called an age of invasion, migration, colonization, or simple settlement.

Professor Susan Oosthuizen maintains that archaeological, historical, and linguistic evidence indicates not invasion and conquest, but continuity and cultural assimilation, as Germanic peoples slowly migrated into Britain and the local British population adapted to their new post-Roman existence.

Using a host of evidence, including genetic analysis of 5th and 6th-century human remains, other historians and archaeologists maintain this was a period of bloodshed and apartheid. Germanic populations eliminated British bloodlines and marginalizing survivors into their relegated communities. Within this complex era of cultural change, the historical Arthur may have risen to some form of power. Although certainly not as a king.

King Arthur Legend

Working from the later traditions to the earliest, historians and literary scholars can peel back the accretions of legend to try to discern a kernel of historical truth. The most significant of all Arthurian authors is Geoffrey of Monmouth. His History of the Kings of Britain, written in the 1130s while Geoffrey was a cleric in Oxford, popularized the Arthurian legend as never before. It incorporated Welsh traditions and works of earlier historians. However, he states that much of his story comes from a “lost manuscript.”

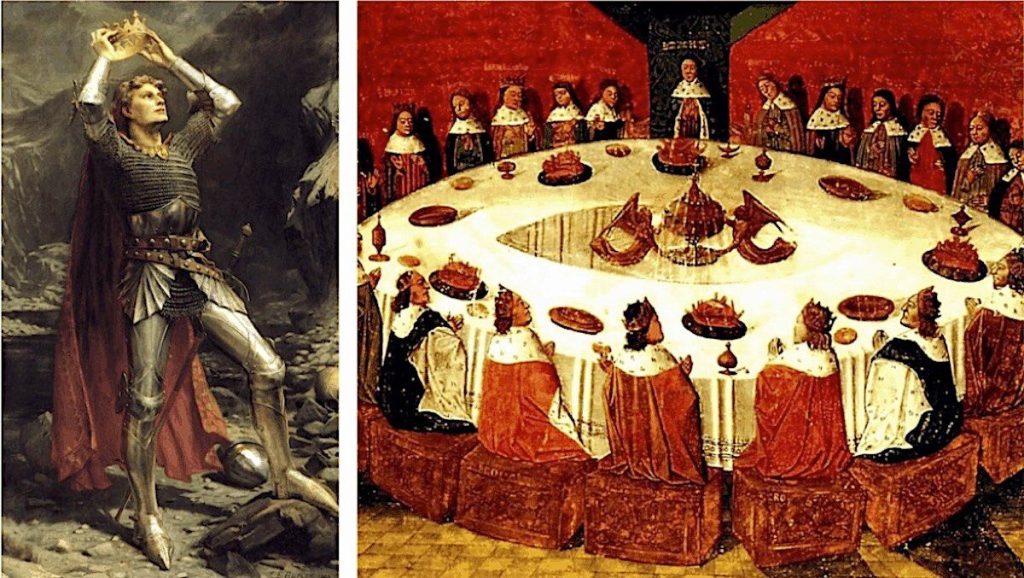

Geoffrey’s history provides a lengthy account of Arthur’s life, from conception to death and entombment on Avalon. An international king of wisdom and power, Arthur was a worthy model for kings of Geoffrey’s own age, a politically fraught era of royal contests for power. While he introduced his readers to many of the landmarks of popular tradition, including Excalibur, Merlin, Tintagel, Camelot, and Avalon, his work is held today as a literary invention with minimal historical merit.

You may also like: Sword in the Stone at the Monte Siepi Chapel

Romance and Christianity

Following Geoffrey, the Arthurian traditions took hold in the romantic literature of royal courts in England and France. Marie de France, Countess of Champagne and daughter of the feisty Queen Eleanor of Aquitaine, patronized Chrétien de Troyes, author of some of the most famous medieval works of courtly love featuring the Arthur and his knights of the Round Table.

In the 12th century, these courtly legends of King Arthur supplanted the historical realities of a warrior Arthur. Arthur became a symbol of Christian kingship. Alongside the tales of his loyal knights of the Round Table, he offered medieval Christians models of behavior to inspire faith and fortitude and to boost recruitment as the Crusades forged on in the Holy Land.

William of Malmesbury and Authentic History

A kernel of historical truth, though, remained alive in the works of William of Malmesbury, a monk, and historian. He who wrote Gesta Regum Anglorum in 1125, possibly while in residence at Glastonbury Abbey. William describes Arthur as warlike, not royal: “It is of this Arthur that the Britons fondly tell so many fables, even to the present day; a man worthy to be celebrated, not by idle fictions, but by authentic history. He long upheld the sinking state, and roused the broken spirit of his countrymen to war.”

Geoffrey of Monmouth, writing only a decade after William, had partially based his fabulous and expansive history on William’s Gesta. William himself was reliant upon earlier Welsh poets, chroniclers, and historians who offered a spare account of the historical and homegrown British hero Arthur.

Welsh Traditions and the Earliest Historical Evidence

Welsh historical traditions never refer to Arthur as a king but as a warrior devoted to Christ and the Virgin Mary.

– Annales Cambriae

The Annales Cambriae, a 10th century chronicle compiled at St. David’s cathedral in Wales, is the first text to offer specific dates for two seminal episodes in Arthurian history and legend.

The first is Arthur’s great victory against the Saxons at Mt. Badon in 516 CE, when he bore the cross of Christ upon his shield. The second entry on Arthur records his death in 537 CE at the Battle of Camlann. He falls by the sword of Medraut, often called Mordred, his son according to legend. The Annales, written centuries after Arthur’s historical existence, place him within other European and British historical events, such as the great plague that swept through the Roman world in 547 CE.

– Historia Brittonum

The deeds of Arthur, the warrior, are offered in somewhat more expansive detail in the 9th century Historia Brittonum, or History of the Britons. Perhaps written by the Welsh monk or cleric Nennius, the Historia is a partisan history of the kingdom of Gwynedd. It liberally mixes legend and myth with history and genealogy. The Historia also provides the core of historical tradition regarding the warrior Arthur. It offers a geographical survey of his twelve major battles, famously culminating in the Battle of Mount Badon, where Arthur killed 960 Saxons in a single charge. In this Historia, Arthur is no king, but a dux bellorum – a Roman title used for military leaders in border territories.

– Y Gododdin

Finally, in the sparest of details, the achingly sorrowful and heroic poem Y Gododdin, written in the 7th century by Welsh poet Aneurin, is the first source to introduce the name Arthur into textual tradition. The poem is not historically reliable, contextualized, or even clear in translation.

Centered in the Northern British kingdom of Gododdin, the poem documents a battle between Britons and Angles near Catraeth in southern Scotland. Arthur appears only once, and as a heroic epitaph made at the death of another warrior who falls in battle. While a bulwark in battle, the fallen Briton Gwawrddur “was no Arthur.” Historians and linguists believe this reference could be an interpolation or later addition. But it stands nonetheless as the first textual reference to a heroic warrior Arthur.

– De Excidio et Conquestu Britanniae

One last text bears some reference, as it is the earliest historical reference to the Battle of Mount Badon. Doleful monk Gildas wrote De Excidio et Conquestu Britanniae, “On the Ruin and Conquest of Britain,” sometime in the early 6th century. Gildas was no fan of British kings of his era. He declared them as petty and constantly warring tyrants who created nearly as much chaos as the invading Anglo-Saxons. Some historians believe that Gildas’s distaste for secular rulers led him to omit their names and to highlight the invasions instead as a just punishment from God for the many sins of the Britons.

You May Also Like: England’s Great Outlaw, Robin Hood: Real or Legend?

His didactic work references Ambrosius Aurelius as a hero of the Britons. A Romanized leader often asserted to be kinsman to a historical Arthur. While discussing the 5th-century wars, Gildas notes that warlords repulsed the invading Saxons at the Battle of Mons Badonicus, Mount Badon. Still, he never credits Arthur for this victory, as do all of the sources previously discussed.

Archaeology of Arthur

The archaeological landscape of England in the fifth and sixth centuries, like most historical evidence, offers no firm evidence of a historical Arthur. But not for want of trying. Archaeologist Leslie Alcock in the 1960s investigated numerous Iron Age hillforts in Somerset, southern England. Built in the 1st century BCE by Celtic Britons, these sites became reused in the post-Roman era as defensive sites against Anglo-Saxon incursions. Excavations by Alcock and others at Cadbury Castle and Glastonbury, among other areas, sought to make connections between the Arthurian age and this post-Roman landscape.

Another Iron Age hillfort and settlement at Tintagel, Cornwall, has been the site of frequent excavation since the 1990s. Tintagel was an aristocratic site occupied after the Roman withdrawal. It is also one of Britain’s few settlements tied into an Atlantic trade network that brought high-status Mediterranean products into Britain. The Cornwall Archaeological Unit has overseen excavations at Tintagel, following work in the 1990s by Glasgow University archaeologists.

In 1998, the team from Glasgow famously uncovered the Artognou stone, bearing a Latin inscription that reads: “Artognou descendant of Patern[us] Colus made (this).” Media reports immediately connected Artognou with Arthur, following Geoffrey of Monmouth’s invention of Tintagel as Arthur’s birthplace. Archaeologists and epigraphers have been more cautious about the affiliation. They remain focused on Tintagel as an exemplary high-status site that happens to be associated with Arthurian traditions.

Verdict and the Afterlife of Arthur

If King Arthur is real, he is rooted in this 6th-century archaeological landscape more than in Geoffrey’s tales or in a hollow oak tree in a tomb in Glastonbury. The search for the real Arthur was reborn in the 20th century as Britain faced unimaginable peril during the bombing raids of World War II. Arthurian novels, films, comics, and video games give this early medieval warrior turned medieval king a new afterlife today.

References:

- Eric John, Reassessing Anglo-Saxon England. Manchester University Press, 1996.

- Roger Sherman Loomis, The Development of Arthurian Romance. Dover Publications, 2000. (Available on Amazon)

- William of Malmesbury, Gesta Regum Anglorum: The History of the English Kings vol. I, ed. and trans. by R. A. B Mynors (Oxford: Clarendon, 1998).

- Arthurian Archaeology