In the second in this series which seeks to understand the life of a great general through the battles he fought, today’s article focuses on possibly the greatest self-made man of the 19th century: Napoleon Bonaparte. Born in obscurity, this Corsican captain rose to proclaim himself Emperor of the French and to redraw the map of Europe.

Napoleon’s tactical genius is without question. But it was in his strategic grasp of Europe and his ability to move his armies quickly to where they could apply the most pressure that allowed him to face off against the great armies of Europe, and defeat them.

Napoleon of course would end up defeated and in exile, but it is in his victories that we see his brilliance. There are other lessons to be learned from his later defeats, but in seeing his endless activity and energy, his clarity of purpose and drive, that we understand how he was able to reshape a continent.

What was his plan? How did he execute it, and how did he know what to do? Here is the life of Napoleon, broken down into his most important battles.

1. The Siege of Toulon (1793)

Napoleon’s first great victory came almost by accident. A lowly artillery captain travelling the coast, he was diverted to Toulon to assist with a thorny problem.

In the chaos after the Revolution Toulon had declared for the king, and in order to defend itself it had invited the British and Spanish fleets under Lord Hood into its harbor. At a stroke, Britain had won herself a strategic Mediterranean port in France without a shot being fired.

Napoleon’s understanding of the power of artillery was what won the day. He understood that a key fort, across the harbor from the city, could threaten the British ships at anchor with cannon fire were it to be taken. The fort was taken, the fleet withdrew, an d the city fell to the French.

2. The Italian Campaign (1796)

After a strangely quiet spell in Nice (which nonetheless saw Napoleon rise to the rank of brigadier general by the age of 24), Bonaparte’s army marched into Italy in 1796. After a lightning series of battles lasting only a month, Piedmont was forced to accept terms.

The key battle was at Mondovi, where Napoleon relied on two things: speed, and independence of action. Trusting to his divisional commanders, he subdivided his force into autonomous units which were to outmaneuver the enemy and overwhelm them. These tactics became a mainstay of Napoleonic warfare.

- (List) Alexander the Great: A Life on the Battlefield

- Napoleon’s Downfall: How did the Little Dictator Lose at Waterloo?

Having forced Piedmont to the table, Napoleon then turned and saw off a large Austrian army heading across the Alps, headed for Mantua. In a series of attacks the Austrian army was reduced to the point where it could not offer sufficient reinforcement, and with a final defeat of a second Austrian column at the Battle of Rivoli, northern Italy was now held by the French.

3. The Battle of Marengo (1800)

Italy was in French hands, but the fighting was far from over and repeated attempts to free the peninsula, supported by the British and Austrians, led to a series of battles and sieges. It would only be at the Battle of Marengo that a decisive victory was won.

The day did not start well for Napoleon, who rose to find himself facing a surprise attack from the numerically superior Austrian army. Bonaparte had been fooled by an Austrian agent into diverting a large part of his force away to the north, and now faced the full might of Austria.

Retreating against the Austrian attack in good order, the French were themselves able to offer a surprise counterattack as the Austrians found themselves strung out in pursuit. In the subsequent rout 14,000 Austrians were killed, the army fled out of Italy, and the peninsula was won.

4. The Battle of Austerlitz (1805)

After a pause for politics and to have himself crowned Emperor in 1804, Napoleon intended his next target to be England. He started to mass troops in Northern France, to the alarm of the growing coalition arrayed against him.

Napoleon saw the gathering storm and the threat of invasion, and so switched his attention from the Channel to the east, and the Rhine. He assembled 200,000 French troops in secret and force marched them over the Rhine to face the Austrians, reinforced by the Russians.

Napoleon managed to flank the Austrian position and force their surrender, and then arranged his army to appear exhausted and out of position, inviting an Russian attack. The Allies leapt at the chance to attack a weakened France, but it was all a ruse, and the French counterattack crushed the center and left both enemy flanks in disarray.

5. The Twin Battles of Jena and Auerstedt (1806)

So much for the Austrians, now for the Prussians. Having secured his territorial gains with the Treaty of Pressburg after Austerlitz, Napoleon moved his army into what is now Germany to the northwest, initially encountering the Prussian army near the city of Jena.

Once again Napoleon relied on speed and the ferocity of his assault to win the day. The Prussians were tough opponents and 5,000 French were killed at Jena, but this was enough to rout the Prussian force and send it back in disarray.

The Battle of Auerstedt, fought at almost the same time, saw Napoleon’s reinforcements blocked from joining him by a huge Prussian army led by King Frederick William III. The quality of training and discipline of the French troops won the day, and the two French columns were able to unite, defeating Prussia in detail along the way.

6. The Battle of Friedland (1807)

Austria, Prussia, now it was time for Russia. Napoleon’s first attempt to crack the Russians led to an uncharacteristically indecisive action at the Battle of Eylau, and in pursuit of a more satisfactory outcome the French army moved to Kaliningrad, on the Baltic Sea.

- The Great Stock Exchange Fraud: Lord Cochrane’s Napoleonic Lies?

- Was Napoleon Poisoned by his Wallpaper?

The Battle of Friedland started with a Russian mistake. A Russian marshal, acting against orders and apparently not an expert on how things had been going recently, decided to divert his force to attack a French division. 60,000 Russian troops started to cross a river and attack the French.

But the French troops were not so easily beaten, and when Napoleon appeared himself with 80,000 the Russians fond they had trapped themselves with the river at their back. The Russian army routed, fell back and then fell to pieces. 40% of the Russians died, many drowning as they fled.

7. The Battle of Corunna (1809)

So now to Spain and Portugal. Napoleon had sought to secure these territories through treaties, and while Spain was willing Portugal was having none of it. Napoleon needed to intervene himself, and so he did, marching into Iberia in November 1808 and Madrid before Christmas.

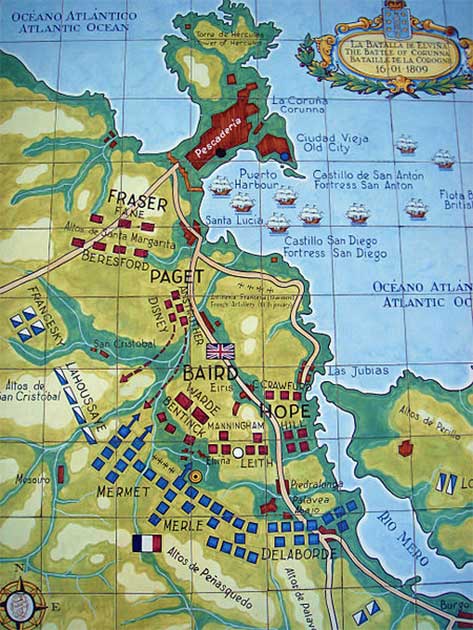

Portugal still resisted, but it was the British soldiers in Spain that concerned Napoleon the most. Under their loved and admired general Sir John Moore, the British had bolstered Spanish and Portuguese armies in battle, and now they faced the French one last time, at the Battle of Corunna.

And Napoleon was defeated. Not in person, to be sure, and Sir John Moore’s decisive victory was won at the cost of his own life, but in another Dunkirk the French were denied their victory and the British escaped.

The British were driven from Spain, but here was Napoleon’s first real mistake: considering the peninsula war all but over, he allowed it “to fester” as he later put it. It would prove fatal.

8. The Battle of Wagram (1809)

But Napoleon had good cause to feel his attention should lie elsewhere: the Austrians were back. Emboldened by the removal of French troops from the Rhine to fight in Spain, Austria invaded Bavaria, a French ally, seeking to win back its position as a major power in Europe.

Napoleon was uncharacteristically caught by surprise, and even more astonishingly lost a battle he personally commanded, the Battle of Aspern-Essling. However, assembling a force of some 170,000 troops Napoleon then decisively took the fight to the Austrians, crossing the river Danube and giving battle at Wagram.

By now Napoleon’s enemies were learning. The Austrians enjoyed a defensible position and Napoleon, despite having more troops, took two days to crack them. Only an enormous artillery bombardment from the French secured victory, and even then the Austrian army escaped.

Conclusion: An Empire in Ten Years

After Wagram comes Russia, and the turning of the tide. There are many lessons to be learned from Napoleon’s later defeats, also, but it is in his victories that we understand what the Little Dictator tried to achieve.

His precision, his speed, the discipline of his troops and his own mystique helped France to victory as he declared war on all of Europe, and beat them every time. Only the Russian winter (and a festering Portugal) could stop Napoleon in the end.

Top Image: Napoleon in 1807 as the master of many battles. Source: Paul Delaroche / Public Domain.

By Joseph Green