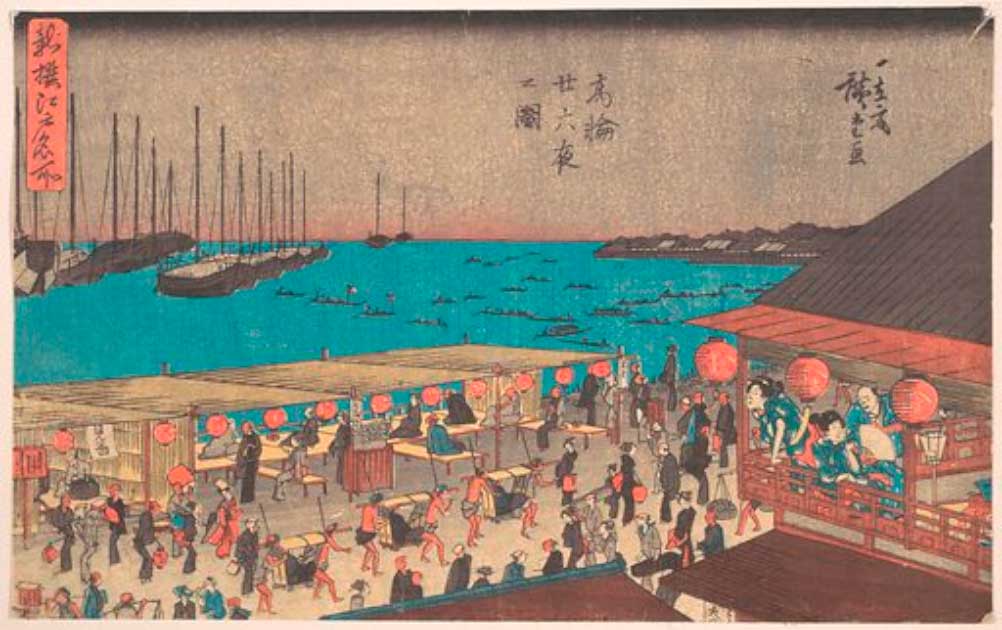

In 1860, Japan was a mysterious country to the rest of the world. For the previous 200 years, in self-imposed isolation, it had chosen to be cut off from the rest of the world. But things were about to change.

After 200 years the first Japanese were finally to leave their once isolated lands, and travel to America. Who better than the ancient Samurai warriors to represent the revered and insular Japanese culture?

This was no whim, and to truly understand the gravity of the Japanese delegation visit you must look at what the years leading up to this event were like for these Japanese nationals. By understanding the new era Japan was entering into we can understand the cultural significance of this. And to do this, we must travel further back into Japanese history.

Japan had experienced unrest, warfare, and volatility from 1467 until 1615. Ieyasu Tokugawa was finally awarded the title of Shogun, the military leader chosen by the emperor, in 1603 after years of warfare against his competitors.

Although the emperors remained officially in charge, the Shogun had far more actual authority over the nation. Tokugawa’s reign as Shogun would lead Japan into the Edo-era, a return to “traditional” Japan characterized by splendid isolation.

Japan Alone

Tokugawa was keen to uphold the peace that had finally been achieved in Japan. He was worried that permitting foreigners from the West to enter Japanese territory might spark turmoil there. The Shogun therefore made the unprecedented decision to impose self-imposed isolation on Japan in 1639, cutting it off from the rest of the world.

The law, sometimes referred to as Sakoku “chained/locked land,” was recognized as the “Closed Country Edict of 1635.” The four classes of Japanese society were not allowed to mix under this order, which was essentially a military dictatorship.

Foreigners and Japanese were both tightly prohibited from entering and leaving the nation, and any violation of this edict was punishable by death. This was in part prompted by the Portuguese, who had established trade networks with Japan and who brought many things from the West, most notably Christianity.

The Shogun was concerned that Western culture and Christianity would diminish Japanese ideals and eventually supplant Japanese culture. Rather than lose the traditions he held dear and see Japanese culture be watered down by European influences, Tokugawa chose to remain separate, and independent.

Remarkably, Japan remained separated from the rest of the world for the next 200 years, and the experiment was remarkably successful from an internal perspective. The country saw substantial growth in its economy and there was nationwide peace throughout this period.

- Where Truth Meets Legend: Was Jimmu the First Emperor of Japan?

- The Story of Utsuro-Bune: a 19th Century Japanese UFO?

However, the increasing globalization of humanity was not something Japan could ignore forever. Pressured by actions of the US Army and the increasing appeal of the foreign and exotic, the power of the Shogunate through the 19th century started to crumble.

Eventually, Japan could remain isolated no more.

Samurai: The Chosen Flagbearers of Japan

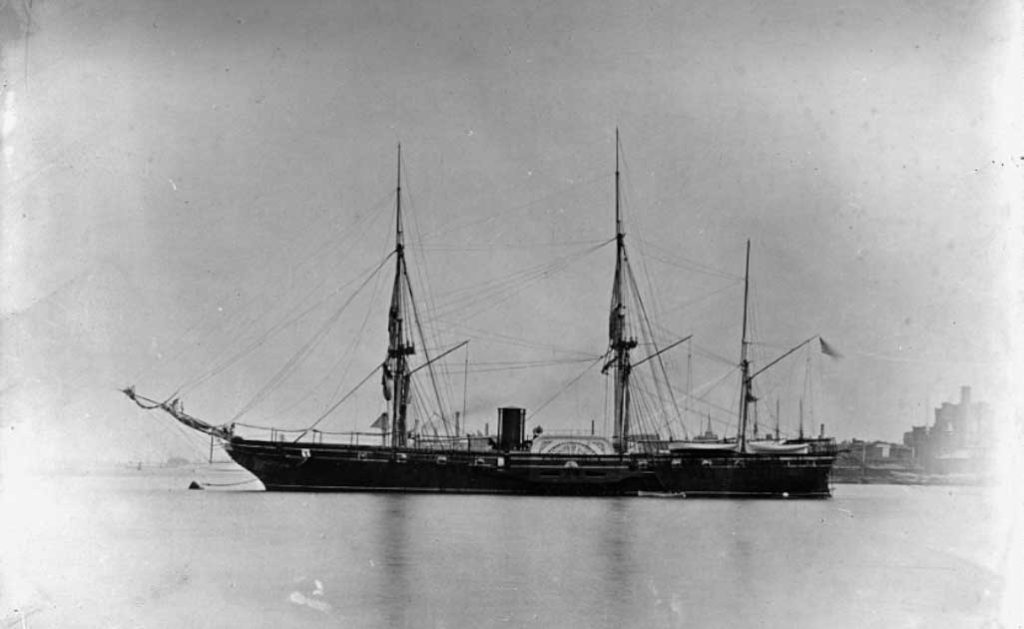

And so it was that the navy ship USS Powhatan sailed from Shinagawa, Japan, in January 1860 on an eight-month journey around the globe. The selected ambassadors embarked aboard these ships were a troop of 87 Samurai, the traditional warrior class of Japan.

They arrived in San Francisco first, where they were greeted by throngs of Americans anxious to see anything of this reclusive and mysterious culture. They traveled from San Francisco to Panama, Cuba, and then took a train across the continent to Washington, DC, where they exchanged the Treaty of Amity and Commerce.

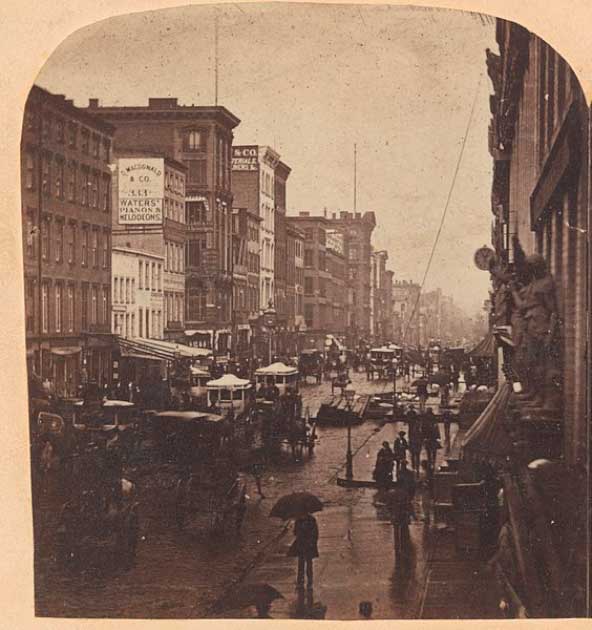

While in DC, they met President Buchanan at the White House. From there they traversed the country once more, stopping in Baltimore briefly before ending the US leg of their tour in New York City.

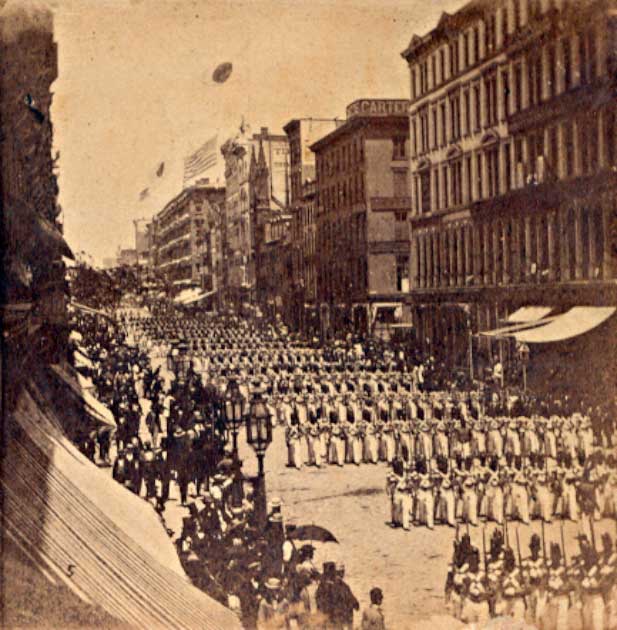

The Samurai received a hero’s welcome when they landed in New York. First thing on their busy itinerary was the “Samurai Parade” down the iconic Broadway thoroughfare. Massive crowds lined the street, with an estimated half a million New Yorkers coming to see the famous “East met West” encounter. The Japanese Samurai and American military officers were both dressed formally.

At the renowned Metropolitan Hotel in Soho, the City of New York hosted a lavish gala for the visiting dignitaries. In an article they published on the visiting warriors, the New York Times called the march “a glorious event that will go down in state history.”

Over the next three weeks the Samurai delegation did what any tourist does when visiting New York City, they went sightseeing to Central Park, university grounds and other famous landmarks within the city.

A Culture Shock for the Samurai

The media coverage depicted the Samurai warriors as “dignified” and “refined” which impressed and intrigued New Yorkers. However one of the Samurai kept a diary, and the writing exposed the fact that their assessment on American society were somewhat different.

He said that the unhealthy, oily cuisine left him and the other warriors with sick stomachs frequently, and he expressed this displeasure in his journal. However, the delegation raved about champagne and ice cream, which he referred to as “a sweet ice dessert that melts in your mouth”.

The United States was anxious to highlight its status as global leader in innovation and technology. One of the Samurai described how their hosts gave them a telegraph machine in an effort to impress the Japanese with this advanced technology. To their dismay the Japanese were not impressed.

The major culture shock for the Samurai was however the degree of freedom enjoyed by the populace. A number of the visitors mentioned how astonished they were to see ladies walking about with their shoulders bare and exposed. For many of the Samurai men, used to the rigid social norms and class structure of Japan, such freedoms were unknown.

What did the Americans Think?

On the American side, people were in awe of the ancient, traditional culture that the Samurai warriors still upheld, from the traditional kimonos they wore to their dignified demeanor. America capitalized on the public’s infatuation with the visitors while they were in the country by marketing goods, creating plays and songs about them, and even creating a cocktail called “The Japanese” in their honor.

- Land of the Rising Sun: Did Jesus Retire To Rural Japan?

- Judge Crater: The “Missingest Man” in New York City

One of members of the Japanese group wrote about how his opinion of Americans changed during his time their claiming that “For the most, the part of this country are extremely generous, honest, and sincere.”

One Samurai in particular caught the attention of the US public, his name was Tateishi Onojro. Onojro, a 25-year-old trainee translator, was the youngest person in the Japanese delegation.

Onojro was referred to by his coworkers as Tamehachi, or just Tame. His name was misheard by the American media as Tommy. With his newly appointed America name Tommy skyrocketed into the hearts and homes of many curious Americans.

The Samurai group participated in many parades, and Tommy often waved a handkerchief that a woman had given him to the cheering audience. A number one hit song was even composed about Tommy as the frenzy around him intensified. He allegedly had a deluge of love letters sent to his hotel rooms.

However, a young, low-ranking Samurai named Yukichi Fukuzawa had the greatest impact on the visit. Fukuzawa asked to be the ship’s commander’s servant because he was eager to learn about the West. Nobody could have imagined how this young boy would eventually come to influence the rapidly changing Japanese society, despite being given the role of servant.

Fukuzawa is remembered today as one of the pioneering intellectuals who assisted Japan’s transition into the modern world and toward westernization. Later, he was recognized for his leadership and his face was chosen to be inscribed on the 10,000 Yen note in his honor. He also went on to he found Japan’s Keoi University in Tokyo.

A Trip Overshadowed

Many of the Samurai were shunned by the Japanese public after returning home. Some of the 87 Samurai soldiers had become Christians while traveling the globe. Christianity has been seen for two centuries as a tool that may undermine the rich, traditional culture of Japan.

And in fairness, that is exactly what happened a few years later in 1867 when Japan’s military rule came to an end, allowing Japan to develop toward a more westernized state. Sadly, the Samurai had introduced into their society the influences which would cause their own destruction.

From this point it was only a matter of time before Samurai warriors themselves would be of no use to Japan as without a Shogun the military did not hold the same authority that is once held. After the Battle of Shiroyama in 1877, just 17 years after their world-wide US tour, the power of the Samurai was broken and their class became extinct.

Things were not rosy in the US either, and an enormous civil war was set to break out in the United States just one year after the Japanese visit. Although only a short visit used to advance US-Japanese relations, it was an important moment in time for both countries, and for the world.

Top Image: The Samurai visited New York after 200 years of isolation. Source: Pictosmith / Adobe Stock.

By Roisin Everard