The massive passage tomb and mound of Newgrange is Ireland’s most significant archaeological site. Built around 3200 BCE, it predates the ancient marvels of Stonehenge and the Giza pyramids by hundreds of years. This complex passage tomb, also called a chambered cairn, sits within a complex Neolithic landscape, littered with other monuments and graves.

It is famous for its astronomical significance, one of a few solstice-marking graves in Europe. Archaeologists are now revealing its mysteries as they revisit the site.

Brú na Bóinne

Located in Ireland’s “Ancient East” in County Meath, the passage tomb is about 50 km north of Dublin. It is part of a complex landscape of monuments collectively called the Brú na Bóinne lying in the fertile valley of River Boyne. The passage tombs of Knowth and Dowth and 90 more graves and monuments adorn the Boyne valley.

Antiquarians explored the area as early as the 17th century, but serious archaeology only began in the 1960s with Professor Michael J. O’Kelly, University College Cork.

The Builders

Archaeologists have debated whether Ireland’s megalithic passage graves were a local innovation or imported tradition. Ireland was home to Mesolithic hunter-gatherers until around 4000 BCE, when a new population migrated from Britain or Brittany. These Neolithic peoples introduced agriculture, a protein-rich diet, and new rituals and beliefs about the afterlife.

Genetic analysis of human bones from passage tombs across Ireland revealed that these Neolithic farmers initiated the construction of megalithic tombs in Ireland.

Construction

Europe has only a few solstice graves, including Maeshowe chambered cairn in Orkney, but none rival the size and spectacle at Newgrange.

While it is not the first passage tomb built in Ireland, it is unquestionably the greatest. In the west of Ireland, two monument complexes at Carrowmore and Carrowkeel boast earlier but smaller passage graves. Carrowmore and Carrowkeel and Loughcrew in the east include elevated plateaus, concentrations of graves, and similar material culture, including artifacts like quartz pebbles and bone pins. All of these features are also found at Newgrange.

The size reveals the power and wealth of its rulers. Massive numbers of workers quarried and transported colossal stone slabs. They moved the turf and boulders used to construct the mound, well over 200,000 tons of stone and earth. Its construction likely took decades.

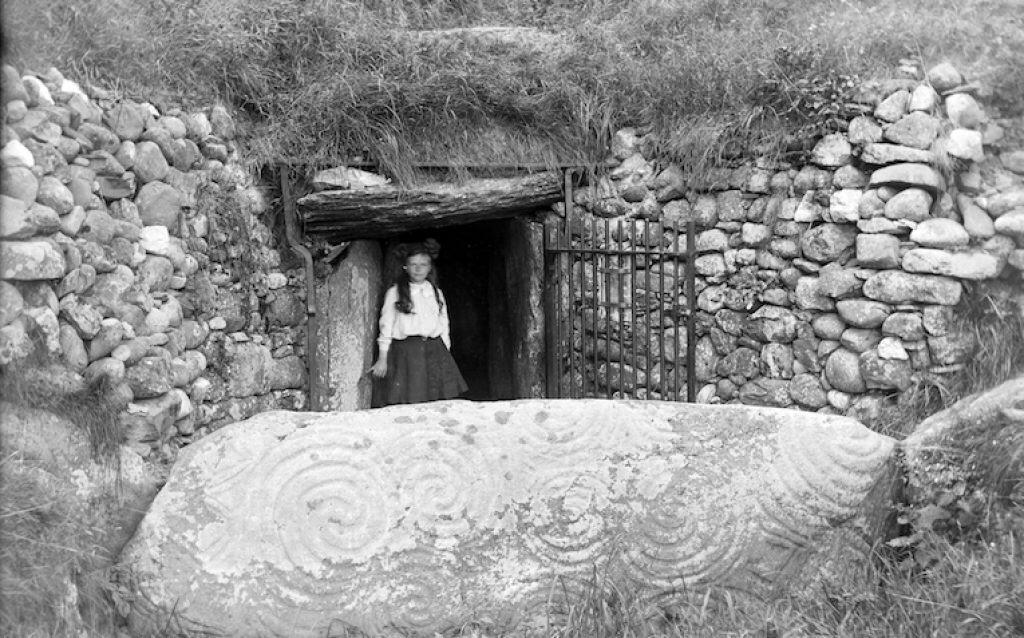

Designed to awe on several levels, those who viewed the passage tomb from the outside would have noted both the massive diameter (approximately 85 meters) and the mound’s height (12 meters). A high wall, or kerb, surrounded the mound, featuring large stone slabs with intricate swirled designs. Gleaming white quartz stones may have decorated an external wall or walkway alongside the mound.

You May Also Like: Mysterious Clava Cairns of Scotland

Just above the passage grave’s entry, a window-like roof box allowed the solstice sun to illuminate the passageway into the central chamber during the shortest days of the year. Over 5000 years ago, after Newgrange’s construction, the illumination would have come precisely at sunrise.

Megalithic Art

Newgrange features some of the most famous examples of megalithic art from Europe. The external kerbstones include a range of symbols and designs.

Cunliffe records some of the art as “zigzags, lozenges, concentric circles, spirals, U-motifs, and radial motifs,” often combined in careful patterns on a single stone.

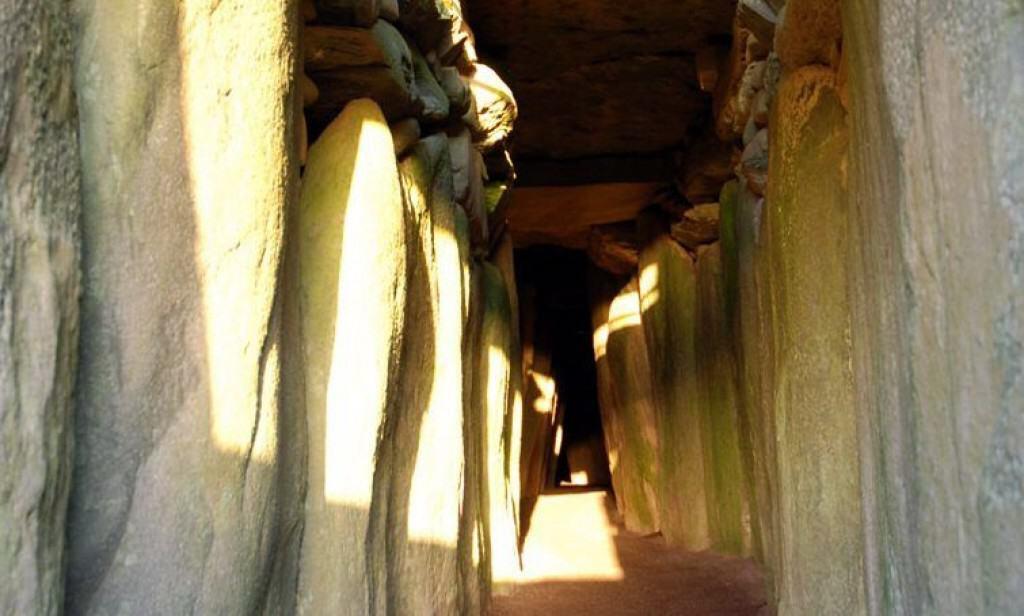

Inside the monument, orthostats and ceiling-slabs include more spiral designs, including triskele or triple-spiral patterns. This ordered artwork lends credence to conceptual design ideas – not simple decoration, but perhaps artwork with cosmic significance.

Interior

Only a select few would have had access to the passage within the mound. Upon entering the passage tomb, crouching visitors would find a narrow 19 meter-long entry passage lined with orthostats, or large stone slabs.

The passage ends at a central chamber area with a high corbelled roof. Three smaller chambers radiated off the central location, each of which included a basin for offerings or as a receptacle for buried remains. The chambers included grave goods of bone pins, beads, pendants, as well as human remains of cremated individuals and one important set of unburnt bones.

The Pharaoh

These unburnt, disarticulated bones belonged to a middle-aged man, labeled NG10 in a new study from Trinity College Dublin. With the only well-preserved remains left in Newgrange, this man was the product of “first-order incestuous union,” designed to keep an elite ruling family intact over the Boyne Valley. The burial of NG10 and his unique bloodline have led scholars to refer to him as an “Irish pharaoh,” indicative of sacred and secular power.

Tomb, Temple, or Holy Site?

Archaeological excavations, remote sensing, and drone surveys have revealed more monuments and features surrounding the area from the later Neolithic Age. Timber circles, crop marks, and even possible quay structures on the River Boyne may indicate travel paths and a ritual cursus, or processional route, leading to the passage tomb. Bronze Age peoples constructed both timber and stone circles around the site.

While Newgrange is clearly about demonstrating the ruling power, its higher purpose may have been more otherworldly. As a solar monument, it would have marked the turn of the year for this Neolithic farming culture, the solstice marking the start of longer days and a new season.

You May Also Like: Stonehenge: A Megalithic Monument of Britain’s Ancient People

This megalithic structure was a sacred space for those who built it, but not a temple or house of the gods. Later mythologies, though, would see it as such.

Mythology and Later History

Newgrange, while not Celtic in origin, became an integral part of medieval Irish mythology. Later Irish myth transformed this massive monument into the burial place of Dagda Mór, chieftain of the Tuatha Dé Danann. The Tuatha Dé Danann were the pre-Celtic supernatural inhabitants of Ireland, driven underground and into mounds when the early Irish came to the island. The great king Dagda oversaw both weather and the harvest, a sun god, fitting for a monument built originally by agriculturalists.

You May Also Like: Cahokia Mounds: The Largest Ancient City in North America

Known as Bruig na Bóinde in these later Irish myths, Newgrange features in the famous tale the Wooing of Étain, thought to be the birthplace of mythic Irish hero Cúchulainn.

The Neolithic or Celtic name for the site remains unknown. The word Newgrange originates from the medieval Christians who eventually controlled the Boyne valley. The term grange refers to an estate or holding of land. At some point, “new grange” was added to Cistercians monks’ property at Mellifont Abbey. The name stuck.

Newgrange Today

Visitors to the site follow a long tradition of ancient and antiquarian tourism. Reconstruction commenced following the excavations in the 1970s and 80s, with recent work completed on both the site and its visitor center. Designated in 1993 as a UNESCO world heritage site, it is among Ireland’s most visited sites. Winners of an annual lottery can witness the 17-minute solstice spectacle inside the passage tomb.

References:

Brú na Bóinne, Archaeological Ensemble of the Bend of the Boyne. UNESCO World Heritage List

L. M. Cassidy, R.Ó. Maoldúin, T. Kador, et al. “A dynastic elite in monumental Neolithic society.” Nature 582, 384–388 (2020).

Barry Cunliffe, Facing the Ocean: The Atlantic and its Peoples, 8000 BC-AD 1500 (Oxford University Press, 2001).

Robert Hensey, First Light: The Origins of Newgrange (Oxbow books, 2015).

Heritage Ireland, Brú na Bóinne Visitor Centre

Michael J. O’Kelly, Newgrange: Archaeology, Art and Legend (Thames and Hudson, 1995).