In recent years, our perception of Vikings has transformed. Once seen solely as barbaric raiders, scholars now recognize the complex and sophisticated culture and ideologies of these Scandinavian raiders. Their seafaring abilities, sense of adventure, and complex mythologies and world views continue to fascinate us. A series of symbols affiliated with their most prominent gods help us better understand their central beliefs. Norse symbols, including Mjöllnir, Yggdrasil, Valknut, Ægishjálmur, and Svefnþorn, reveal the earliest Viking warrior culture. These ideas embody the strength, cunning, and power associated with these North Atlantic warriors.

Sources for the Symbols

Archaeology perhaps offers the best testament to early Norse symbols and traditions. The metalwork from graves like Købelev in Denmark, images from runestones in Sweden, and various objects from ship burials in Norway help us reconstruct early Norse beliefs.

Textual sources from Iceland provide the most precise descriptions of the powerful symbols and images that defined traditional Norse thought. The two Eddas, the Poetic Edda, and the Prose Edda offer insight into pre-Christian Norse traditions. The Poetic or Elder Edda is a collection of works by anonymous authors, orally composed in the 10th century. Written down in the 13th century, it includes heroic tales, including both Creation and Ragnarök. Most famously, it also includes the Hávamál, the sayings of Odin, and the Völuspá, or the sayings of the Vala, a seer or priestess. Here the reader finds the origins of the Norse mythological and ethical world.

Based on the Poetic Edda, Snorri Sturlusson’s Prose Edda is a more accessible source for Old Norse beliefs. Snorri, a powerful Chieftain and Christian, wrote the Edda to preserve both poetic tradition and the ancestors’ beliefs. As with the Poetic Edda, Snorri’s book includes the Norse creation epic, and tales of the major gods, including Odin, Thor, Loki, the Aesir and Vanir, and the main geographies of the Norse universe.

Finally, the Icelandic sagas are the pearl of Old Norse literary tradition. Exciting stories, historical and mythical, of the Viking Age, these 13th to 15th-century works, some epic in length, detail travels, politics, economics, law, and supernatural encounters. The Islendingasögur, or Family Sagas, is the most famous, but the Fornaldarsögur, or Legendary Sagas, offers wild and mythological tales of heroic encounters with trolls, witches, and shapeshifters.

Symbols of the Viking Age

The earliest symbols of Norse culture date from the Viking Age (circa 790-1100) or before. Indigenous Norse symbols are relatively few in number but are repeatedly seen in many Norse stories and artifacts. Norse people also used more common ancient symbols, like the swastika, found in many premodern European and Asian cultures.

You May Also Like: Vikings Introduce Native American DNA To Iceland

Mjöllnir: Thor’s Hammer

Easily the most well-known of all Norse symbols, the hammer of Thor, Mjöllnir, was the primary weapon of the god of thunder. Forged by dwarfs, Mjöllnir was the mightiest weapon of Asgard. Thor used it to protect both his realm and that of humans. Additionally, the hammer was thought to be used in consecration at weddings, births, and deaths.

Norse people embraced the Mjöllnir symbol in a range of contexts. Most common are small silver pendants or amulets worn by warriors and found in graves across pagan and medieval Scandinavia.

Even as the Viking Age ended and the Norse world became Christian, Mjöllnir was too culturally engrained to abandon. Archaeologists have found molds for the production of reversible pendants, featuring Thor’s hammer on one side and a Christian crucifix on the reverse.

Thunderstones, or dynestein, are small pebbles, flint stones, or white quartz found across the Scandinavian world. The Norse believed them to be byproducts from Mjöllnir, falling from the sky during his battles. These stones could be deposited in graves or built into houses and served as an extra level of protection.

Yggdrasil: The World Tree

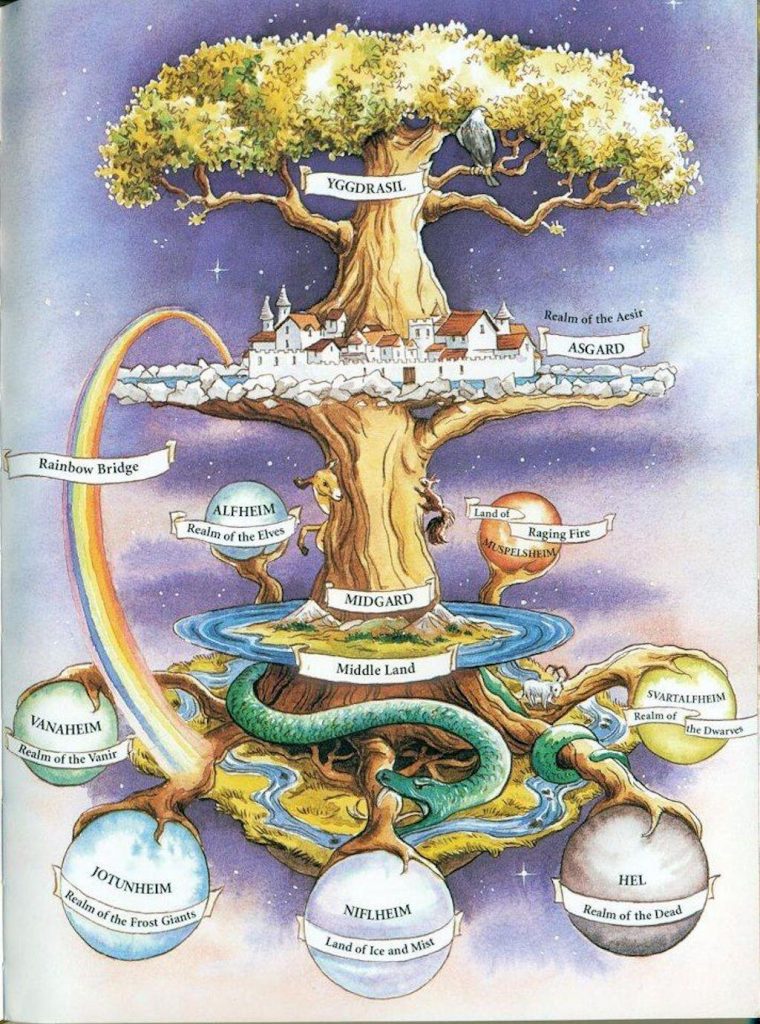

Both Eddas describe Yggdrasil, the World Tree. Called “the largest and best of all trees” in the Prose Edda, sacred Yggdrasil is the giant tree that connects the Norse universe’s nine realms. Ambiguity surrounds the structure of Yggdrasil’s universe, whether the nine realms exist vertically or concentrically around the tree. The gods hold court in Asgard, and warriors reside in Valhalla, all found in the interlaced limbs of the world tree Yggdrasil.

Creatures travel the extent of the tree; the serpent, Nidhogg, gnaws ominously at the roots, while an eagle, with the hawk Veðrfölnir perched atop its head, sits in the upper branches. Busy squirrel Ratatosk travels the trunk, bringing gossip to the realms. At the base of Yggdrasil is Mimir’s well, where Odin trades an eye in exchange for a drink, giving him both wisdom and intelligence.

Related: Yggdrasil Tree of Life and Nine Worlds of Norse Mythology

Yggdrasil is perhaps too complex to appear as a whole in most Norse artwork. Some art historians have speculated that interlace found at Urnes Stave Church, and maybe even on other woodwork or metalwork, could represent Yggdrasil’s intertwined roots and branches.

Valknut: Odin’s Knot

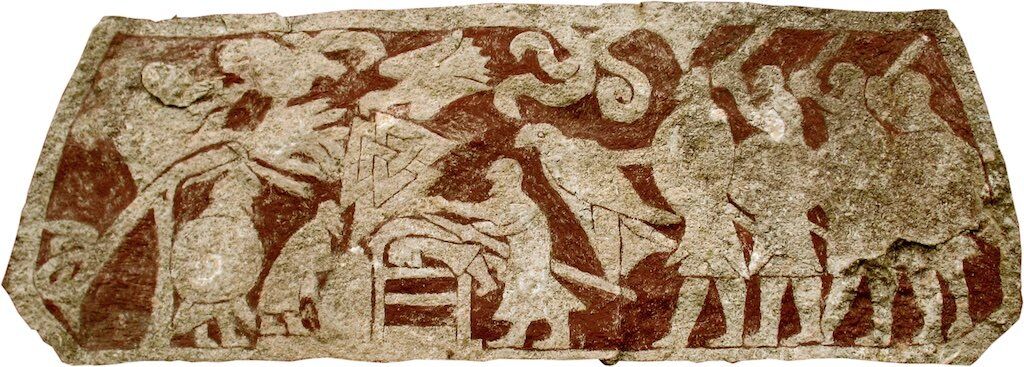

The valknut consists of a series of three interlaced triangles and often referred to as the symbol of Odin. The knot resembles the familiar triskele, or three-part knot, common in Danish and Swedish runestones, like the Funbo runestones of Uppsala, Sweden.

The valknut may represent the power of an oath. On the Stora Hammars stone in Gotland, a valknut symbol is above a man who lies prone on a surface. Another man above him bears a weapon, and two birds close in the frame. This imagery may represent the consequences of a broken vow, particularly a vow given to Odin. The two birds could be Huginn and Muninn (Thought and Memory), the two ravens who sit by Odin on the throne.

The nine corners of the triangles could represent the nine worlds that encircle Yggdrasil. In this respect, the concept of an oath could also be present, as the nine worlds were linked and maintained peace only through Odin’s power to bind.

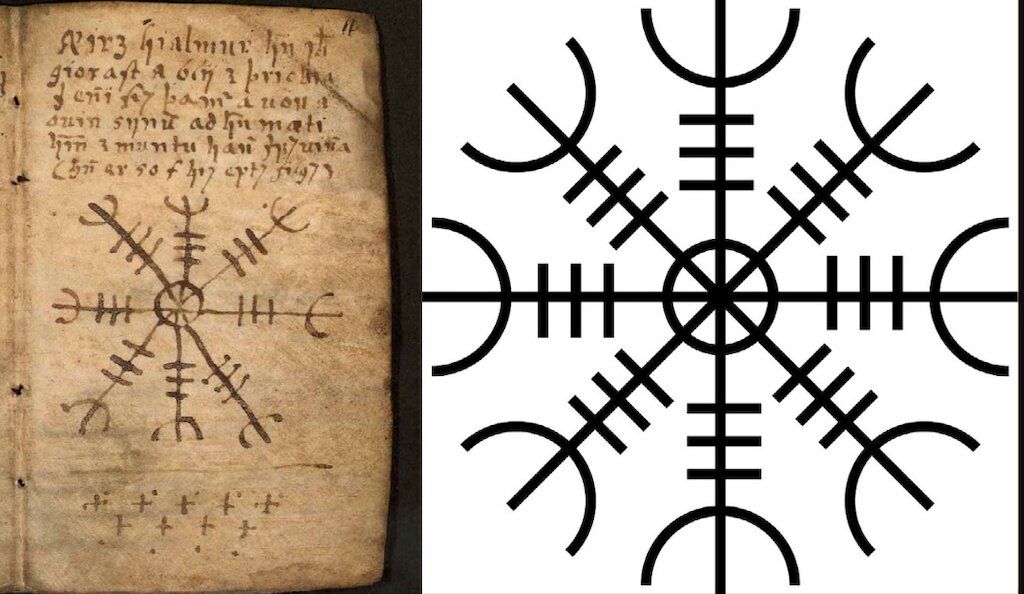

Ægishjálmur: Helm of Awe or Dread

Early text translations like in the Saga of the Völsungs and the Prose Edda describe the Helm of Awe (Aegis-Helm) as a helmet or a defensive weapon. It does not appear in early artifacts or art, unlike most of the other symbols.

In the Prose Edda, the Aegis-Helm appears in the battle of Sigurd the Dragon Slayer. Fafnir kills his father, Hreidmar, out of lust for gold. Following the murder, he claims his father’s helmet, the Aegis-Helm, or Helm of Dread, which “brought fear to all living things when they saw it” (Skaldskaparmal, 7). He then transforms into a serpent or dragon, lying atop his ill-begotten gold.

You May Also Like: Mysteries of Surt’s Cave: Bandits, Mutilations, and the Fire Giant

In the Saga of the Völsungs, Sigurd fights and kills the transformed Fafnir. Having dealt a death blow to the dragon, Sigurd and Fafnir discuss gold, greed, and kinship:

Have you not heard that all people are afraid of me and my helm of terror?… I have borne a helm of terror (Aegishjlamur) over all people since I lay on my brother’s inheritance. And I blew poison in all directions around me, so that none dared come near me and I feared no weapon.’… Sigurd said ‘This helm of terror you speak of gives victory to few, because each man who finds himself in company with many others must at one time discover that on one is the boldest of all

Byock, Saga of the Volsungs, ch.18

The manuscripts that preserve images of Ægishjálmur change the image over time, from the defensive weapon of the Völsung saga and the Edda to a stave-based protective symbol.

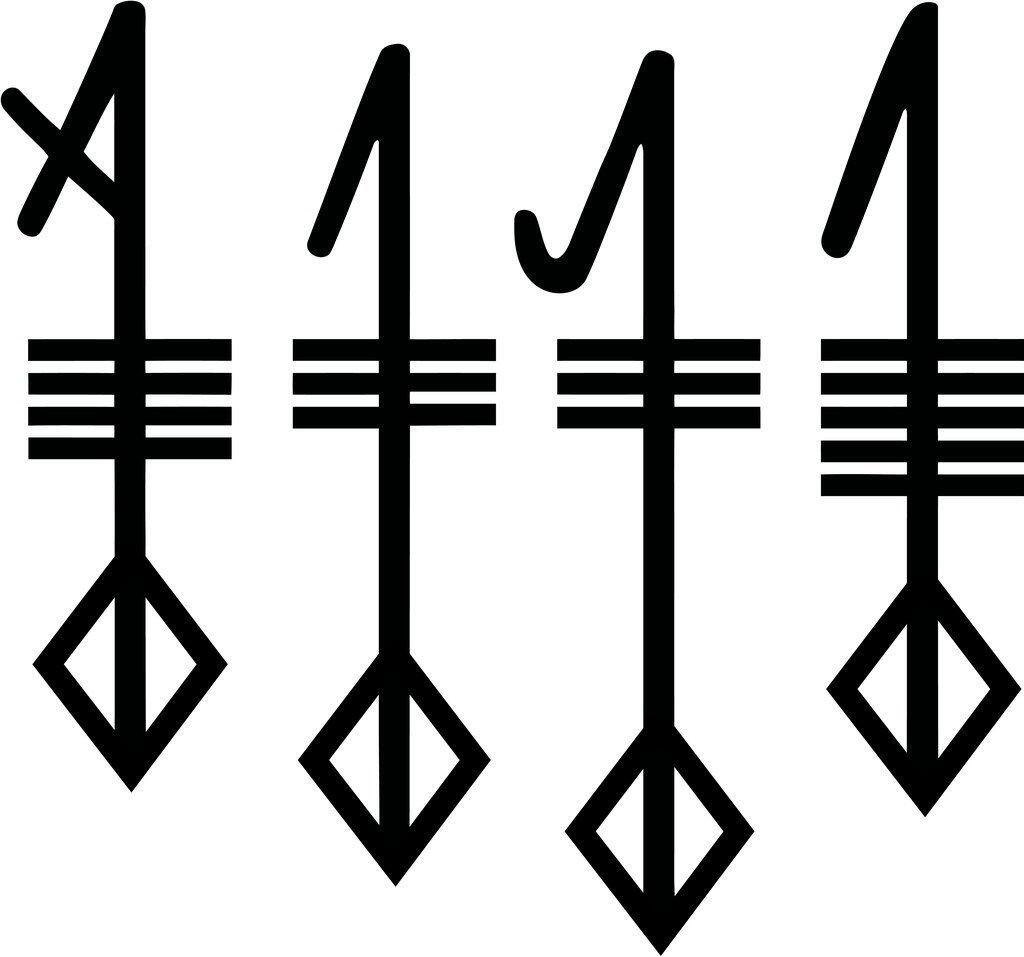

Svefnþorn: Sleep Thorn

No medieval manuscript or artifact seems to depict the Svefnþorn. In modern depictions, it contains four hooked lines, sometimes associated with runes. It may have been carved and used as a curse upon enemies to set them into a deep sleep. However, the sagas indicate the sleep thorn was wielded as a weapon.

Several sagas describe the Sleep thorn, including two legendary sagas – The Saga of King Hrolf Kraki and Gongu-Hrolf’s Saga. It also appears in the aforementioned Saga of the Völsungs, deployed by Odin against the Valkyrie Brunhild. When awoken by the hero Sigurd, slayer of Fafnir, Brunhild explained her precarious state:

What was so strong that it could slash through her coat of mail, ‘and rouse me from sleep… I struck down Hjalmgunar in battle, and Odin stabbed me with a sleeping thorn in revenge.

Byock, Saga of the Volsungs, ch.21

Norse Symbols and White Supremacy

In the 20th century, Norse symbols became adopted by Nazi propagandists as symbols of ethnic purity. In the late 20th century and even today, white supremacist groups continue to misappropriate Norse mythologies as symbols of a false era of racial purity. Groups identified by the Southern Poverty Law Center and other organizations as Neo-Völkisch hate groups have displayed Norse and Germanic symbols.

Related: History of the Swastika and Its Fall From Grace

References:

Thomas A. DuBois, Nordic Religions in the Viking Age (University of Pennsylvania Press, 1997).

H.R. Ellis Davidson, Gods, and Myths of Northern Europe (Penguin, 1964).

John Lindow, Norse Mythology: A Guide to the Gods, Heroes, Rituals, and Beliefs (Oxford University Press, 2001).

Saga of the Volsungs, transl. Jesse Byock (Penguin, 1990).

A. Somerville and R. McDonald, The Vikings, and their Age (University of Toronto, 2013).

Snorri Sturlusson, Prose Edda, transl. Jesse Byock (Penguin, 2006).