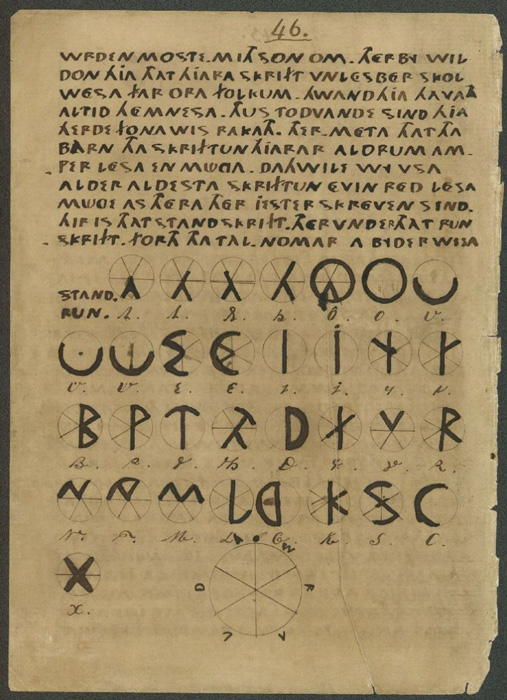

In 1867 the world of European history was thrown into confusion by the mysterious appearance of a manuscript. Known as the “Oera Linda” Book, this document, written in an Old Frisian dialect, claims to include historical, mythical, and religious topics from the distant past, stretching back from the 9th century AD as far as the third millennium BC.

The document was initially hailed as a new source for Europe during the dark ages and before, filled with secrets. Jan Gerhardus Ottema (1804–1879), an expert on ancient Frisian, published a Dutch translation in 1872 and proclaimed the text to be genuine. However, from the first, there were doubts.

By the time the translation was available the book was already at the center of a fierce debate as to its authenticity, as it had been since the document first became known to the general public in the 1860s. By 1879, everyone agreed that it was a recent invention, and today the document is considered a fraud or forgery by experts in Germanic texts.

Nonetheless, the book continues to fascinate. It was a centerpiece of Nazi occultism in the 1930s, and it is occasionally mentioned in esoteric fringe literature, sometimes associated with the legend of Atlantis. But, if a fraud, why was it created in the first place?

The fact is, we just don’t know. It is unclear whether the goal was to create a deliberate fraud, a parody, or whether this was simply a flight of fancy on somebody’s part. This mystery has passed down through the decades and is certainly part of the book’s fascination today.

One of the more recent attempts to understand the book comes from historian Goffe Jensma. According to Jensma, it was most likely intended as a joke, but written in the understanding that it would potentially fool some nationalist Frisians (a region that includes parts of Germany and the Netherlands) and orthodox Christians, two ideologies who have ever clung to evidential straws to support their world view.

Is the Oera Linda manuscript a fake? And why did it appeal so much to nationalists and fundamentalist Christians?

Where Did It Come From?

The story of the Oera Linda manuscript starts in the year 1867 when Cornelis Over de Linden (1811–1874) first produced the manuscript, which he claimed to have received from his grandfather via his aunt. De Linden showed it to Eelco Verwijs (1830–1880), the provincial librarian of Friesland, for translation and publishing.

The text was rejected by Verwijs, but a Dutch translation was published in 1872 by Jan Gerhardus Ottema, who believed it was written in authentic Old Frisian. However, it would seem that Ottema had overlooked several problems with the text when concluding it was authentic.

- Voynich Manuscript: Undeciphered Medieval Book

- The Hidden Text of the Sanaa Manuscript: A Prototype Quran?

For a start, the text contained many anachronisms, both in content and in style. Although the possibility of its being genuine was still debated for several years, by the end of the decade it was largely accepted to be a fake, albeit a clever one.

Preaching to The Choir

Perhaps what made the Oera Linda Book so popular was its content, and the great history it purported to contain. The manuscript wrote of a great Frisian history which had previously been undocumented, describing the Christian nation ruled by just leaders, victorious in battle, at the heart of Europe.

No wonder orthodox Christians and those hungry to learn of Frisia’s great past rushed to support the book: it was, after all, a gift to nationalism, allowing those who wanted to believe it to reconstruct their glorious Frisian history they had long hoped for. As a parody of 1870s Frisian nationalism, it seems to have been altogether too successful.

However, when a notable Frisian antiquarian took the joke seriously and published a translation and commentary which treated it as authentic, it became clear that the joke had gone too far. Once some sections of the populace had accepted it as true, it became much harder to dismiss as a joke.

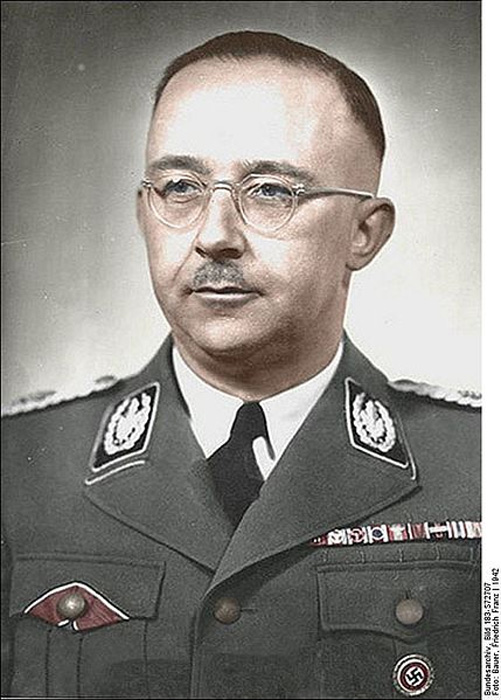

While it was widely acknowledged as a fake by the late 1870s, it would continue to appear whenever it suited the ideological narrative of the moment. Thus it was translated into German in 1933 and was characterized as the “Nordic Bible” by Nazi Germany in 1934, proving inspirational to Himmler.

Himmler used the text as the basis for his own Nazi mythology (Friedrich Franz Bauer / CC BY-SA 4.0)

From the late 1970s onwards, it would again become popular, this time among neopagans alongside the Neo-Nazis. These groups seemingly all share a common purpose in support of the manuscript, in that they feels their search for historical support for their nationalism has been rewarded.

Such as approach does not make for sound research. The groups who claim to believe that the text are genuine share similar motivations, and look to the text to legitimize their current actions, rather than as a lens for understanding the past.

The study of history should be about understanding where we came from and ancient texts are useful as a lens through which to understand the writer, and the society they were writing for. Those who seek to endorse Oera Linda do so not for this reason, but because they need legitimacy in the present day.

The Oera Linda manuscript tells us nothing about Frisia during the dark ages, then. Where it does shine a light is on those in 1870s Frisia, and after, who sought to believe the hoax, and why they so readily accepted the fraud.

The Fake History of Continental Europe

The Oera Linda manuscript offers nothing less than a complete, secret history of Europe. The text, described as a satire of the Christian Bible, writes of a matriarchal, Germanic society ruled by a priestly class and dedicated to worship of the goddesses Jrtha (the earth mother) and Frya (daughter of the creator god).

- Codex Gigas Devil’s Bible: Weird Medieval Manuscript

- Joseph Smith Papyri: The Ancient Egyptian Gods of Mormonism

The interrelationship such a society would have with other, known civilizations which existed in Europe at the same time is largely ignored. European history undergoes a radical change to assert Frisian dominance, which ranges from vague assertions that Frisia was the pre-eminent society in Europe to truly outlandish claims such as the Frisian alphabet predating Greek, or Phoenician.

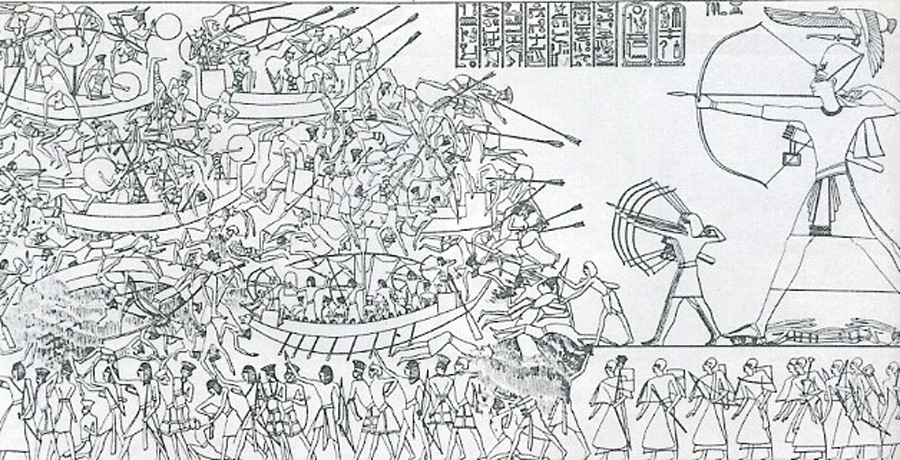

The book includes a lengthy description of a sea battle between Egypt and Phoenicia in the Aegean Sea, as well as a global disaster which echoes the Biblical flood. It then follows a section of the Story of Wenamun (supposedly the first such surviving account, if you believe the claimed dates of composition) at one point. Other historic events are given a new spin also, such as the Bronze Age Collapse or the arrival of the Sea Peoples in the eastern Mediterranean.

The text itself is made of several smaller compositions, with the earliest portion supposedly written in 2194 BC, a gross anachronism for such a text but apparently necessary to give the manuscript the sense of authenticity and primacy. The text itself seems to fall apart in the final sections, although whether this is artful and deliberate or due to authorial ennui is unclear.

One particular section has also proven appealing to modern pseudohistorians. Certain passages of the book describe “Atland”, a name used in the 17th century to refer to Atlantis. Prompted by this, modern Atlantean enthusiasts have seized on the manuscript as further, ancient evidence that Atlantis was real.

But none of this is true. Either Cornelis Over de Linden or Eelco Verwijs (or possibly an acquaintance of both men) are the two most likely authors, writing a comedy text to poke fun at an overtly nationalistic audience in the late 19th century. It was likely never to be taken seriously.

Useful Propaganda

So, is the manuscript worthless? As an ancient record of Europe it can tell us nothing, an exists as a work of speculative fiction, by a modern writer and for a modern audience.

However, as a work of its time it is very revealing. Through its reception and popularity it highlights the undercurrent of Frisian nationalism in the 19th century, and the belief being encouraged at the time that pride in your country was tantamount.

Those who seek to drum up nationalism will often obscure the truth. From the US Marine Recruiting Sergeant promising naïve teenagers the world, to jingoistic tabloids seeking to drive newspaper sales through divisive, provocative headlines, the elements of society who foster such beliefs will seize on anything that offers support for their position.

The world of Oera Linda was not real. But nationalists, first in Frisia and then with the Nazis, found it very useful in their attempts to stir up the masses in their support. Supporters of Atlantis, in framing this text as evidence for their lost continent, should be wary of falling into similar traps.

Top Image: What made some people believe that Oera Linda was genuine? Source: inarik / Adobe Stock.

By Bipin Dimri