There is a little-known but true sabotage incident in the United States that occurred during World War II. In June of 1942, the Nazis put a plan in motion to infiltrate and attack America via the East Coast beginning with two four-man teams. Codenamed Operation Pastorius by German military intelligence, the plan was ambitious from the get-go. However, what was initially designed to sabotage and disable key military targets turned into an embarrassing series of events.

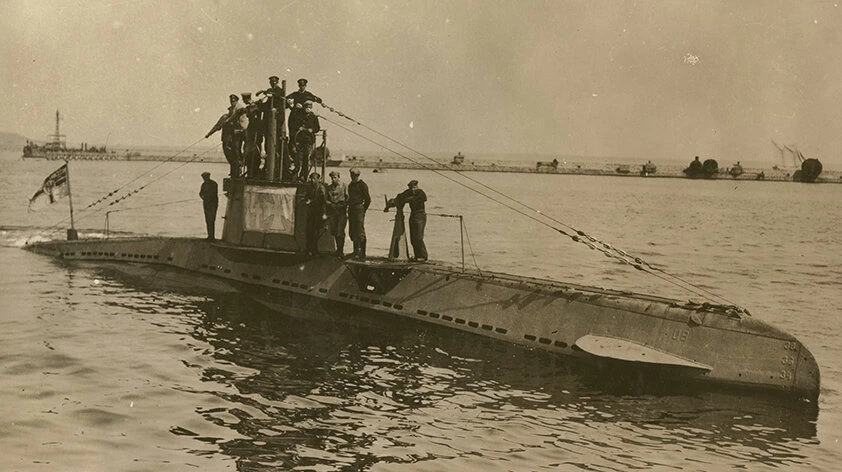

German U-Boats dropped eight German spies off New York and Florida. Public domain.

[blockquote align=”none” author=”Richard O. Johnson”]Terrorism did not make its first appearance on our shores on 9/11. Had Operation Pastorius been successful, serious damage could have been done at a strategic moment, not only to the American infrastructure but also to the morale of a nation dragged reluctantly into what they regarded as a foreign war.[/blockquote]

What Was Operation Pastorius?

The primary goal of Operation Pastorius was to cripple the production of military equipment and supplies, which the U.S. had been furnishing to countries fighting the war against the Nazis. A German submarine would drop eight saboteurs off the coasts of New York and Florida under the cloak of night.

From there, the group planned to split up, and over the next two years, they would travel to major cities. Using their insight and familial contacts to fit in and remain undercover, they would hatch their plans to destroy a number of targets. The Nazis had carefully chosen these targets not only to impede the wartime production but to also instill chaos and fear within the American population.

Targets and Cities

Targets included the Horshoe Curve railroad pass and repair station at Altoona, Pennsylvania, aluminum plants in Illinois, Tennessee, and New York, train stations, hydroelectric plants, bridges, and other manufacturing plants.

Team One headed for Long Island, New York, while Team Two targeted Ponte Verda Beach, Florida. The two teams would land a few days apart but would rendezvous on July 4th in a Cincinnati hotel to properly coordinate their malicious mission.

By our modern standards, we may call these men terrorists. However, as they were enemy agents of a nation with which the United States was officially at war, the men of the Pastorius operation were technically saboteurs.

Recruitment

The Nazis had scoured the records of the Ausland Institute to find their men. This German organization kept track of the political affiliations of its citizens who moved overseas and those who returned to Germany. In this case, the Nazis were particularly interested in those who had lived in the United States. Many of the members were also in the German-American Bund, an American pro-Nazi-Fascist organization. This group focused on speaking out publicly in favor of Hitler and against the would-be Allies and their treatment of Germany.

The Ancient History of the Swastika

In an abstract twist, the Bund even once managed to amass twenty thousand followers at a rally in Madison Square Garden around this time period. The organization was radical and known to be violent. Officially, the German Reich distanced themselves from it. However, as we know now, Nazi Germany actively recruited from their ranks.

Operation Pastorius Saboteurs

Chosen for their familiarity with the United States, the men who made up the team were of German heritage but had been born or grew up in the U.S. Lieutenant Walter Kappe, a Nazi loyalist who had spent considerable time in the States headed the whole operation consisting of two teams. Kappe had been active in the Bund and also held office in the Ausland Institute. The other members were as follows:

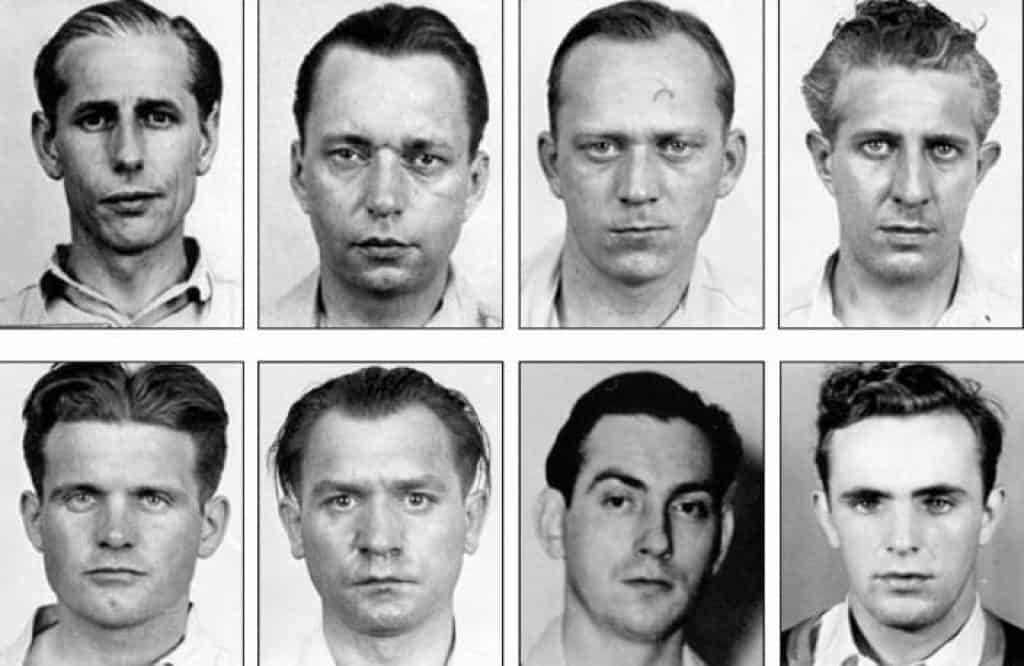

Eight Nazi spies that attempted sabotage of the U.S. in Operation Pastorius. Top: Dasch, Burger, Heinck, Quirin. Bottom: Kerling, Thiel, Haupt, Neubauer. Source: FBI Files.

Team One

- George John Dasch – Team One Leader. As a veteran from the final months of the First World War, Dasch had actually spent more of his military career as an American Private than a soldier in the German Imperial Army.

- Ernest Peter Burger – Fled Germany for the USA to escape brawling charges related to his time in the Nazi Party. He became a naturalized citizen in 1933 but returned to Germany to become a Brownshirt when Hitler gained power.

- Heinrich Harm Heinck – Machinist at Volkswagen who had returned to Germany before the start of the war out of duty to his country of birth.

- Richard Quirin – Also spent time in the U.S. Ironically, Quirin had worked for General Motors in the States while also participating in the Bund. This self-proclaimed Nazi loyalist directly assisted with the allied war effort.

Team Two

- Edward Kerling – Team Two Leader. Immigrating to America in 1929 to work as a butler and cook. Eventually getting back to Germany in 1940, Kerling ended up working at the infamous Ministry of Propaganda, run by Joseph Goebbels.

- Herman Otto Neubauer – Aware of his ideologies, Kerling recommended Neubauer for the operation.

- Herbert Haupt – At only twenty-two, Haupt was the youngest member of the operation. Having moved to America with his parents when he was only four, he was also potentially not the best choice as he was an all-American young man and a U.S. citizen barring his Germanic heritage.

- Werner Thiel – A member of the Bund and a metal worker in a German war plant.

Preparations for Nazi Sabotage in the U.S.

Long before the submarines departed for America with its malicious cargo, the cracks in Operation Pastorius were beginning to show. During training, Team One leader George John Dasch left Top Secret documents on a train. At a bar in Paris, another member of the team drunkenly told fellow patrons he was a secret agent. Although these were signs of how the mission would unfold, they pressed on.

With only eighteen days of intensive sabotage training covering everything from Jiu-Jitsu to demolition tactics on factories and infrastructure, the team made final arrangements and packed their cargo. To travel easily within the U.S. they took along a wide variety of counterfeit documents, including birth certificates, licenses, and Social Security cards. Amongst their sabotage equipment were large quantities of explosives, primers, and detonation devices. The group also stored some German liquor and uniforms for the trip.

Surprisingly, the members of Operation Pastorius were given $175,000 in American currency that would support the team’s efforts for the remainder of the war. Adjusted for inflation, that is over 2.5 million dollars. On May 23, 1942, the two teams received their assignments. Team One was assigned targets with a focus on affecting the aluminum production of America, ideally to cripple or at least dampen it. Team Two was assigned a number of targets focused on disrupting the nation’s railways. They also intended to wreak chaos with the bombing of Jewish owned department stores.

A Rocky Landing

Team One arrived on a Long Island beach near Amagansett, New York, in the early morning of June 13, 1942. Unlike Team Two’s smooth landing in Florida, when they landed a few days later, Team One’s landing was anything but seamless. In an effort to land the team as close to the shore as possible, the U-boat had become temporarily stuck on a sandbar.

The men came ashore wearing German Kriegsmarine (Marine Navy) uniforms, presumably to obey the Rule of War regarding spies. Unlike general enemy combatants who need to be taken as prisoners of war, spies can be shot on site. They changed into their American civilian ensemble and buried their crates of munitions and equipment to retrieve later. As they walked up the sandbank, a stranger appeared on the cusp of the dune.

A Run-In With the Coast Guard

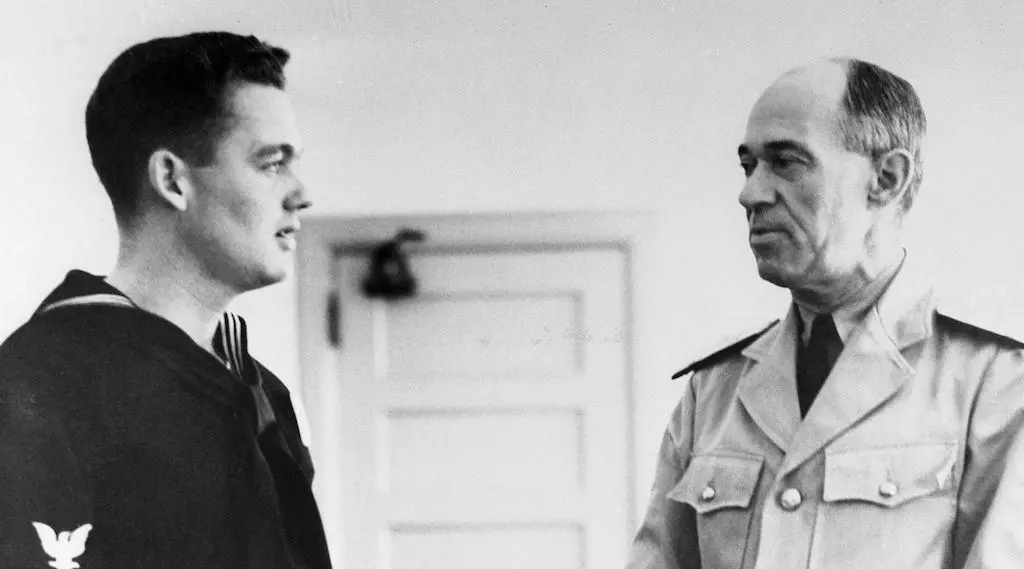

John C. Cullen was a Second Class Seaman in the Coastguard. Unbeknownst to everyone in the German spy team, they had landed alarmingly close to the Coast Guard Station at Amagansett. Cullen was on his familiar nightly foot patrol along the beach when he came across what appeared to be a lone figure walking out of the mist. After demanding the stranger to identify himself, Dasch claimed he and his team were beached fishermen from Southampton.

John C. Cullen receives congratulations from Vice Admiral Russell R. Waesche (right), Commandant of the United States Coast Guard . Credit: Bettmann.

After some menial back and forth, it seemed the German had the situation under control. That was when another member of the team reached the peak of the dune and shouted out something in German. Dasch then gave Cullen $260 as a bribe and instructed him to forget about what he had seen and to leave.

Digging for Spies

Threatened but keeping his wits about him, Cullen faked compliance, took the bribe, and made his anxious journey back to the Coast Guard Station. Although the other members of the Coast Guard initially thought Cullen was joking, the evidence at the beach was irrefutable. Many pairs of footprints led from the surf, and freshly turned earth was present. Upon excavation, they found the malicious cargo of explosives, money, and uniforms. Most startling, however, was the silhouette of a German submarine they could see leaving the shore. Seeing this, they alerted the FBI, which launched one of the largest manhunts in American history. Meanwhile, Dasch and his men found their way to a train station and headed to New York to carry out the operation.

Betrayal Within the Ranks

In retrospect, Dasch’s lenient behavior with Seaman Cullen on the night of the landing evidenced his lack of loyalty to the Nazis. Modern historians, however, question how long he intended to defect and betray the team.

However, the actions of the group as a whole demonstrate either an ineptitude for the mission or voluntary sabotage of the operation. From the comfort of five-star hotels, the teams planned Operation Pastorius between fine dining at restaurants and shopping trips to the same Jewish-owned department stores they planned to blow up.

Many experts believe that Dasch had intended to defect to America all the way along. Upon both teams’ arrival in Cincinnati, Dasch made his intentions known. He invited Team One’s most devout member, Ernst Burger, into his hotel room to include him in his plans to go to the FBI.

Contacting the FBI

After his own persecution at the hands of the Nazi government, Burger was only too happy to abandon the original plan. Concerned about how to proceed with their defection, they decided that they would contact the FBI directly. George Dasch called ahead and gave them the name “Pastorius” and announced that he was heading to Washington for a meeting.

Was the Nazi Bell “Die Glocke” a Secret Weapon?

In his mind, he imagined that the American Government would quickly recognize him as a hero for foiling Operation Pastorius. Little did he know, his call had gone through to the “Nut Desk.” When he arrived in Washington, he called the FBI from the hotel and again gave them the name Pastorius. The FBI quickly went to the hotel he was staying at and picked him up for interrogation. Even upon his arrival at the FBI headquarters, they bounced him around between agents as no one believed his story. It was not until he handed over more than 80 thousand dollars to the agent that anyone took him seriously.

Dasch offered the names and locations of everyone in the two teams. Surely, he would receive a full presidential pardon. Within ten days all eight would-be saboteurs were in custody. However, unbeknownst to Dasch, the Director of the FBI, J. Edgar Hoover took full responsibility for the arrests as if he had figured out this enigma without the help of the loose-lipped German.

The Trial of Operation Pastorius

Franklin D Roosevelt – America’s Wartime President – assembled the first military tribunal since the one that sentenced Lincoln’s assassin in 1865. The effort to create this coalition was to sentence the German spies to death. Between July 8th to August 4th, 1942, the secret Nazi invaders stood trial. All eight were guilty of four charges around the Law of War and espionage.

Trial of the Nazi saboteurs, Washington D.C. 1942. Library of Congress.

Although all received the death sentence, J. Edgar Hoover and the Attorney General informed President Roosevelt that Burger and Dasch had turned themselves in and provided the details of the operation. As a result, the president commuted their sentences. Ernest Burger received a life sentence and George Dasch got a 30-year stint. All the other saboteurs were executed at the District of Columbia Jail on August 8, 1942.

The FBI caught one more undercover Nazi spy who supported the agents of the Pastorius plan. Carl Krepper had gone to seminary school in the U.S. during the early 1900s and returned to German in 1935 in support of Nazi ideals. Hitler sent him back to the states in 1942 to assist the spies in Operation Pastorius in case they needed documents, money, or other support. In 1944 while working undercover as a pastor in the Lutheran church, he was arrested, found guilty of espionage, and served his sentence in prison for six years.

In 1948, President Harry Truman deported Dasch and Burger to American-occupied Germany. Although Dasch thought that he would become a national hero in America, the government branded him a traitor and barred him from entering the country ever again. Nevertheless, the president granted both men clemency and freed them in Germany.

The Cold German Reception

The Nazi government had fallen years prior. Thus, both men returned to a defeated country with no one interested in their sacrifice. However, Peter Burger attempted to bring media attention to the way Dasch had betrayed the team and caused the deaths of six men. With the failure of the operation, Hitler and the German Naval Intelligence did not continue their grand plans of sabotage. Operation Pastorius turned out to be little more than an embarrassing debacle for the Nazis. Peter Burger died in 1989 and George John Dasch followed suit in 1992.

Another Spy Attempt

In 1944, the Nazis implemented another plan called Operation Elster when they dropped off two more German spies on the coast of Maine. Their goal was to gather intelligence on the American technical and manufacturing process. The FBI captured both of them the same day as they made land.

As it happened, a seventeen-year-old boy scout saw them attempting to use a compass on a main local road. He was immediately suspicious. When the scout retraced their steps, he found that their footprints appeared from the surf. Immediately, he contacted the authorities.

The Nazi Errorists

If not for its lack of climax, a director like Wes Anderson or Taika Waititi could translate this kooky tale into an Indie Film. In fact, a movie based on Operation Pastorius, They Came to Blow Up America, came out in 1943. The sheer incompetence of the team sent to sabotage economic targets in the U.S., however, was undoubtedly a blessing in disguise. If fully realized, the operation would have deployed independent sabotage cells fortnightly and killed ten of thousands of people. It is impossible to imagine the havoc and damage to American morale and fighting capacity that would have occurred had they pulled it off.

References:

Klein, Christopher. “When the Nazis Invaded the Hamptons.” History.com. A&E Television Networks, June 12, 2017.

Johnson, Richard O. “The Nazi Spy Pastor: Carl Krepper and the War in America by J. Francis Watson (Review).” Lutheran Quarterly. Johns Hopkins University Press, March 21, 2016.

“Nazi Saboteurs and George Dasch.” FBI. May 18, 2016.

Prior, Leon O. “Nazi Invasion of Florida.” The Florida Historical Quarterly 49, no. 2 (October 1970): 129–39.

Putnam, Christopher S. “Operation Pastorius.” Damn Interesting. Damn Interesting, June 13, 2016.