In the 15th century, proving your identity was more of a challenge than today. There was no identification card or DNA test to confirm you are who you say you are. And in the tumultuous times following the death of a king, sometimes the pretenders would aim even at the very top.

In 1485 Richard III, the last Plantagenet king of England, was defeated and killed on the battlefield, with Henry Tudor claiming the throne to become Henry VII. Although this was the final, decisive victory in the famous Wars of the Roses, this was far from clear at the time.

Henry VII faced many challenges to secure his throne. England was full of powerful nobles, kingmakers and feudal lords who looked to influence the throne wherever possible. And, should the young King Henry prove intractable, there were always more pliant contenders for the crown to be found.

Henry’s own questionable legitimacy to the throne (claimed through his mother, who aside from anything else was still alive at the time) encouraged dissent and rebellion in his early years as king. Two alternative claimants appeared to the throne.

We now know the two pretenders were named Perkin Warbeck and Lambert Simnel, but at the time there was some uncertainty as to who had the better claim. And with the royal family in disarray there were many missing nobles with a better claim than Henry.

Lambert Simnel

The first challenge to Henry’s crown came barely a year after he defeated Richard III. Richard’s faction, the Yorkists, remained undefeated in spirit and were plotting Henry’s overthrow. And then a convenient figurehead appeared.

Lambert Simnel was presented as the Earl of Warwick, Richard III’s nephew. The real Earl was a similar age to the young boy and the political machinations of the time had seen him imprisoned in the Tower of London, the formidable Norman castle which for centuries had held political and aristocratic prisoners.

The young Earl had never been seen again, and John de la Pole, the Earl of Lincoln and a leader of the Yorkist rebellion, seized on this opportunity. Along with Richard Simon, a priest from Oxford, the Yorkists presented Lambert Simnel as this legitimate claimant, free and backed by an army.

Where Lambert Simnel had come from is less certain. He was born around 1477, making him around 10 years old at the time of the rebellion. Various sources claim different parentage, but it is definite that he had a humble origin. Simon undertook his training courtly manners and etiquette to complete his disguise, spreading the rumor that he had sheltered the “Earl” after his escape from prison.

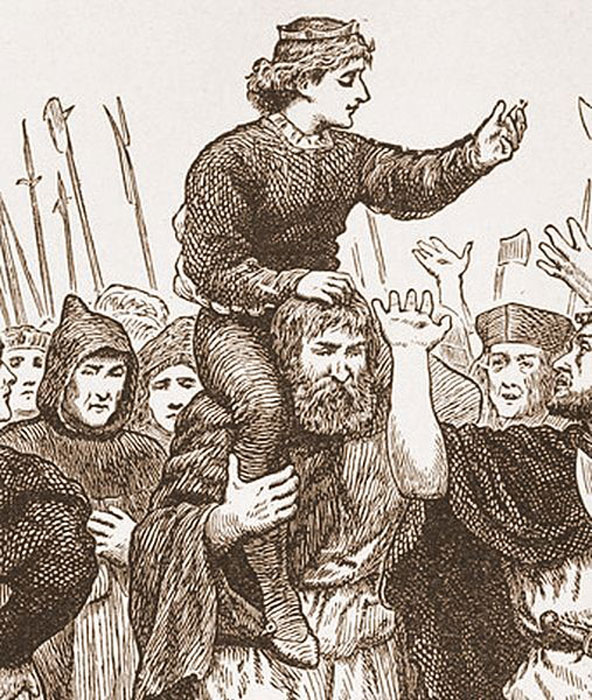

Lambert Simnel was crowned on 24 May 1487 as “King Edward VI” at Christ Church Cathedral in Dublin, Ireland. The Earl of Lincoln proclaimed Simnel as the rightful successor of King Richard III, with a better claim than Henry.

Lincoln went to Burgundy, where Margaret of York, the aunt of the real Earl of Warwick, was staying. There he gathered an army of Irish troops and 2,000 Flemish mercenaries to support his claim.

- Princes in the Tower: A Mystery of Missing Royalty

- Living the Lie: Who Was the Mysterious Man from Formosa?

After Henry VII was informed about this, he also started gathering troops. Henry was therefore prepared for the pretender, forewarned of events and bolstered by the lack of English support for Simnel. The army of Henry VII suppressed the rebels.

Henry had an unexpected trump card in his hand with which to defeat Simnel. The real Earl of Warwick, long imprisoned in the Tower, was in fact still alive. Henry was able to unmask the pretender as an imposter, and the rebellion foundered.

Henry had survived the first major rebellion against his throne. But the next pretender, a thorn in Henry’s side for much of the next decade, was a far more serious opponent.

Perkin Warbeck

Perkin Warbeck claimed himself as the direct heir of King Edward IV. Edward had two sons, Edward V and Richard, Duke of York, who were both imprisoned in the Tower by their uncle, Richard of Gloucester.

The so called “Princes in the Tower” disappeared mysteriously and Richard claimed the throne, becoming Richard III. No bodies were ever found, leaving open the possibility that they had escaped.

In 1490, Warbeck appeared at the court of Burgundy on the continent, claiming to be Richard the younger of the two princes. Warbeck explained that Edward V, his older brother, had indeed been killed, but that he was spared due to his young age.

Warbeck also claimed he had been forced to take an oath not to reveal his identity for some years, in return for being spared. He had stayed in Europe under the protection of Yorkist loyalists from 1483 to 1490 but now intended to return to England.

In 1491 Warbeck travelled to Ireland and John Atwater, the ex-Mayor of Cork, supported him. This was a turning point in his fortunes. Charles VIII of France welcomed him, and although Henry was quick to block French involvement through the Treaty of Etaples, the support of the French king sent a powerful signal.

He also received support from the sister of Edward IV, his supposed aunt. Whether she truly believed him as her nephew or considered him an imposter is unclear, but she publicly supported his cause.

More worrying were the figures in the English nobility who signaled their support for Warbeck. Encouraged, the pretender made several landings in England with small armies in the 1490s.

The Crown Responds

Henry dealt with this threat decisively. The nobles who supported the pretender were executed after show trials in 1495. Henry’s army met the first invasion force in 1495, crushing the attack before Warbeck had even made it to dry land.

- The Mysterious Case of Tichborne and His Stolen Identity

- The Witch-Queen of England? Revisiting Anne Boleyn’s Guilt

Forced to flee, Warbeck was welcomed by James IV of Scotland. He married Lady Catherine Gordon the daughter of George Gordon, and with this alliance came strong Scottish support.

In 1496 Warbeck and James IV crossed into England. The invasion was disastrous as Warbeck failed to find the hoped-for public support in England. And when Henry offered James his daughter in marriage, the offer was accepted and Scottish support for the pretender melted away.

Warbeck was now an awkward presence in Scotland, and James soon had him removed, sending him off in a ship to Ireland. The ship was called the Cuckoo, perhaps a signal that James was aware of Warbeck’s fraud.

Warbeck returned to Ireland and attempted to besiege Waterford, an Irish city loyal to Henry. This again failed and, forced to flee with only 120 men remaining, Warbeck made one last, desperate landing in Cornwall in England.

Cornwall, then as now an independent minded part of England, provided Warbeck with 6,000 men to march on Henry. But this last throw of the dice amounted to nothing, and this time, Warbeck was captured, surrendering in panic at the approach of royal forces.

Warbeck Confesses

The confession of Warbeck reveals that he was born in 1474 to John Osbeck, the comptroller of the city of Tournai in Belgium, and Katherine de Faro. At the age of 10, Perkin was learning Dutch, and then he learned from various masters before finding employment with John Strewe, an English merchant.

Then he travelled several countries, before a Breton merchant hired him and brought him to Cork, Ireland, in 1491, where he learned to speak English. After he was seen wearing silk clothes, some Cork citizens honored him as a member of the Royal House of York. This led to the decision to claim that he was the younger son of King Edward IV.

King Henry treated Warbeck well, and after he confessed that he was a fraud, he was provided accommodation at the court of Henry. His wife became a handmaid to Henry’s queen. But after remaining in court for eight months, he tried to escape and was soon recaptured. Imprisoned in the Tower, he was hanged as a commoner on 23 November 1499.

A Sign of the Times

Lambert Simnel was treated more kindly. Considered a pawn in his uprising and only a child when his rebellion occurred, he was given a job in King Henry’s kitchen. Later he became a falconer for the king, and never showed the slightest inclination to rebel again.

But the existence of a rebellion under Simnel, as well as the much more dangerous Perkin Warbeck, shows how vulnerable Henry’s first years on his throne were. He had won the crown through military victory and a dubious claim, and this left him open to the same thing happening to him.

Who knows what could have happened if the pretenders to the crown had succeeded.

Top Image: Henry’s first years on the throne were beset by rebellion. Source: Tony Marturano / Adobe Stock.

By Bipin Dimri