Kensington Palace is one of many royal estates in the heart of London. Flanked by immaculately pedicured gardens, the enormous castle holds great history as the residence of a number of kings and queens and royalty today. But an often overlooked former member of this household is that of a young child named Peter, also known during his day as Peter the Wild Boy. Because he was found in the woods living like an animal and unable to speak, most people believed Peter was a feral child. Nonetheless, he was a gentle soul with a jovial nature and everyone adored him. Featured a number of times in the ornate murals and artwork on the ceilings of the Palace, Peter was a beloved resident that deserves to be remembered.

Origin of Peter the Wild Boy

One day in 1726, King George I of England was hosting a dinner party near Hamelin, Germany, when some local folks presented a young boy of about 12-15 years old. The townspeople had found the boy the previous year in the Hertswold forest, all alone and nude, except for an old shirt collar that still hung around his neck.

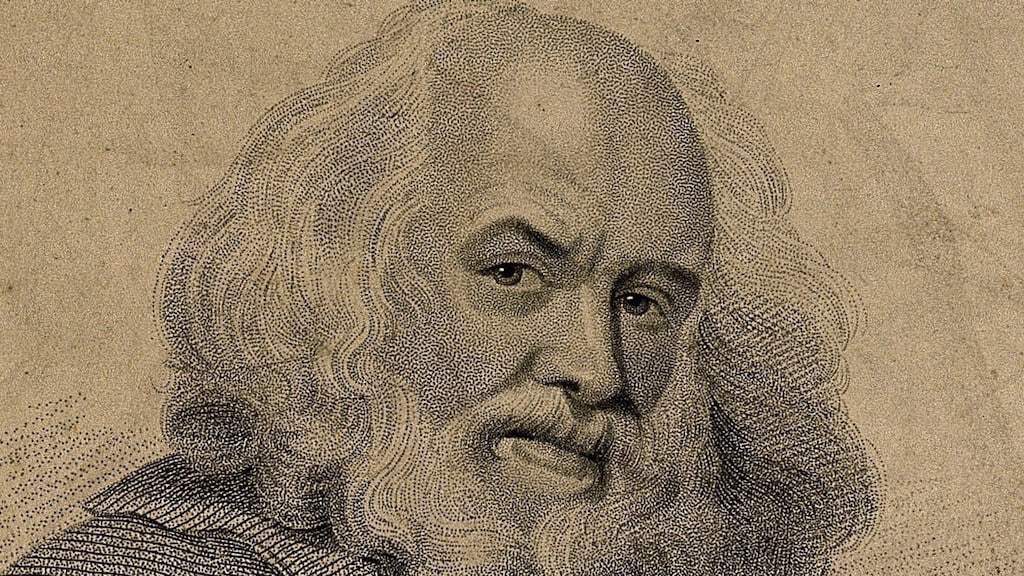

It appeared that the boy had been fending for himself for quite some time. A thick bushy mop of hair sat atop his head, and his green eyes scanned the details of the room as he scuttled up to the king. The child lacked any verbal or social skills and, to the men, appeared “wild,” albeit curious and cheerful.

Naturally, everyone wondered how the child had gotten into this predicament. Had he wandered into the woods and gotten lost? Or sadly, had his parents cast him off as a young child because they were unable or unwilling to adequately care for him?

Unfortunately, child abandonment was not uncommon. If someone could not care for a child or if there was something physically or cognitively wrong with the child, the parents might abandon him in the woods somewhere outside the city where he would likely die of exposure or starvation. (Lewis, 2016).

Peter Goes to Britain

In any case, Peter had miraculously survived. The Princess Caroline of Wales, the King’s daughter-in-law, requested that Peter come to London, and in 1726, he joined them at Kensington Palace. She entrusted Peter to Dr. Arbuthnot to oversee his education and socialization, while another team of servants oversaw his care.

The reputation of this “feral” child from the Hamelin woods spread, and there was much chatter within British society. Everyone knew him as Peter the Wild Boy. At first, he ate with his hands and preferred not to wear clothes. Life in the palace was, at first, distressing for him. In fact, his caretakers wrestled him into his suits each day. Instead of sleeping in bed, he preferred the hard ground in the corner of the room. Although he initially crawled on the floor, he learned to walk upright. Also, like other children, Peter had to learn what discipline was about and received his share with a “broad leather strap.”

Although characterized by his rambunctious behavior, everyone loved Peter. He was cheerful most of the time and absolutely loved music. During his time at the palace, he grew especially close to one of the Queen’s bedchamber women, Mrs. Titchbourn.

Philosophical Debates

In the courts and houses of aristocrats across Europe, there was a fascination with the concept of “feral.” The king once invited Peter to a royal dinner where Peter shocked everyone by devouring his meal only with his hands. He was also known for pickpocketing and “stealing kisses” from fellow courtiers.

During this time, Peter the Wild Boy was the subject of philosophical and moral debates on the nature of man. According to Lucy Worsley, curator of Historic Royal Palaces, they asked questions such as, “If he has no speech, does that mean he has no soul? Do human beings really have souls?” (BBC).

Peter was treated very well, however, because he once ran away later in life and was missing for a number of days, he did wear a collar with his address and reward information should he get lost again. He was indeed renowned for his unsolicited adventures.

Early Development

Physically, Peter did not appear to have anything wrong with him, except for the fact that he had two webbed fingers on his left hand. But although Dr. Arbuthnot diligently worked with him, he could not teach Peter to speak at all. On the contrary, the energetic child loved music and could easily learn and hum the melody to a song after hearing it only once.

Emotionally, Peter had a range of feelings like anyone else. He expressed joy, anger, and the like, and only when there was inclement weather, he tended to be edgy and sullen.

The End of Palace Life

Eventually, Peter left the care of the doctor, and Mrs. Titchbourn assumed his care for a healthy annual stipend. She took Peter to a farm where she would spend her summers with Mr. Fenn. It was a lush burrow that could have closely resembled the place he was discovered in many years earlier. From that point forth for a number of years, Mr. Fenn cared for Peter for a pension of 30 pounds per year.

After Mr. Fenn passed away, his brother, Thomas Penn took Peter to live at a farmhouse called Broadway. Peter lived here in relative joy with several successive tenants for the rest of his life. It was during his adult life that Peter seemed to improve the most in his development.

Sometime during his later years, Peter began instruction with a man, Mr. Braidwood, who taught students with disabilities such as deafness. Mr. Braidwood taught Peter a number of words that allowed him to answer simple questions. He knew his own name. If someone asked who his father was he answered, “King George.” “Bow-wow” meant the dog. He also knew how to count to a low number. Although he never initiated speech on his own, he seemed to understand just about everything anyone was asking him. (The Scots Magazine, 1785, 12).

Did Peter Have a Disability?

Although Peter received excellent care, everyone believed that he was simply a feral child from Hamelin. They did not consider that perhaps he had a genetic condition. With a modern understanding of cognitive and physical disability, historians have been able to analyze the case of Peter the Wild Boy with new eyes. Lucy Worsley first thought Peter was likely autistic. However, upon further analysis, she believes he may have actually had a far rarer disease called Pitt Hopkins Syndrome. This is a disease that has many overlapping symptoms with Autism and also causes delayed learning and motor skills.

Pitt Hopkins Syndrome is a rare genetic condition characterized by symptoms including:

- Limited Height

- Thick Curly Hair

- Hooded Eyelids

- Pronounced curves in the upper lip, sometimes called a “Cupid’s bow mouth”

- A dislike of clothes

- Fusing of fingers

- Complete lack of or minimal speech

These are all features present in artistic depictions and accounts of Peter the Wild Boy. Interestingly, instead of his webbed-fingers, the artwork portrayed his hands holding leaves or branches.

Last Days on the Farm

Peter spent the last 15 years or so of his life with one last caregiver, Farmer Brill, to who Peter had grown very attached to. Farmer Brill was likely a kind man who allowed Peter to help him around the farm in various ways. Peter loved to drink gin and eat raw onions, and he rarely went anywhere without Farmer Brill. Nor did he ever run away during this time.

You May Also Like: Boy Jones: The Peeping Stalker of Queen Victoria

James Bennet, a Scottish Judge and Philosopher, visited Peter and said that Peter was in good health and sporting a great white beard. Another visitor said that he looked like Socrates.

Peter lived approximately seventy years of life. When his caregiver Farmer Brill died suddenly, Peter became despondent and refused to eat anymore. A few days later on February 22, 1785, Peter the Wild Boy passed away. He was buried in Northchurch and his grave is now a heritage site.

In one fell swoop, Peter’s life went from the forest to one like nobility at Kensington Palace. The child who was probably cast off by his parents in his youth survived and found himself amongst the most powerful people in the known world at the time. He is fondly remembered for the joy that he brought to so many. If Peter could have told his own story, it would have been a magnificent story to tell.

References:

Lane, Megan. “Who Was Peter the Wild Boy?” BBC News. August 08, 2011.

Lewis, Margaret Brennan. Infanticide in Early Modern Germany. The University of Virginia. 2012. (PDF Download).

Worsley, Lucy. “Peter The Wild Boy.” The Public Domain Review. April 26, 2018.

“Pitt-Hopkins Syndrome – Genetics Home Reference – NIH.” U.S. National Library of Medicine.

Sands, Brymer, Murray and Cochran. The Scots Magazine. Vol. 47. Princeton University,1785. Digitized 2008.