The Roman Imperial period saw one of the most aggressively expansionist policies ever adopted on a large scale. The Romans launched themselves into an all-or-nothing attempt to conquer the entirely of western Europe, leaving the stamp of Roman architecture and Roman culture on lands as far apart as Turkey and Scotland.

During their centuries of growth the Romans encountered many other cultures whom they dismissively referred to as “barbarians” (as in “blah blah, we don’t understand what they are saying”). Many of these were exotic, but almost all of those weaker than the mighty armies of Rome were ultimately conquered, subsumed and absorbed into the empire.

However, this is not to say that the Romans did not encounter “problematic” barbarians who did not relish the opportunity to become Roman. Britain, protected by treacherous seas and full of hairy natives, was a particular problem.

Although Britain did eventually fall to the Romans, in the far north was Scotland, full of an enigmatic and even hairier people. And here the Romans finally met their match. Despairing of ever dealing with these strange peoples, the Romans were forced instead to build a huge wall across northern England to keep them out.

Who were these warrior folk, who faced the Roman legions and defeated them? The Romans knew then as the painted people for the blue woad bodypaint they always wore into battle (although trousers were apparently optional). We know them still by this name, although untranslated: they were the Picts.

A Mystery People

Sadly for modern archaeologists, the fact that the Picts were never conquered means that the information we have on them is extremely limited. We know some of what they built, through the archaeology which survives. We know some of how they fought, through Roman descriptions.

But how they lived and who they were is far trickier to understand. And, most enigmatic of all, we do not know what ultimately happened to them, and why they disappeared.

The first mention of the Picts was made by a Roman chronicler in 287 AD. For the next seven centuries, from various documents written by outsiders like the Irish and the Welsh, we know they continued to live free in the wilds of Scotland. But from 900 AD onwards they simply disappear.

- Mysterious Clava Cairns of Scotland

- How the Darien Scheme Changed the History of Scotland’s Independence

They appear to have lived in a loose confederation, similar to the later tribes of Scotland. Their unification apparently predates the coming of the Romans, or may have been a response to Roman expansionism, but there is no record of who brought them together, or how.

For much of their existence nothing is known of these tribes. They were fearsome and fearless warriors, fighting largely on foot and apparently given special powers by their druids through their warpaint. They would resist any encroachment on their territory, aided by the difficult terrain that they seemed to know by heart.

Only in the 7th century do we start to see written records which offer a picture of the Picts in detail. One chronicle talks of seven Pictish kingdoms making up Pictavia, but it is unclear whether this is a legendary history.

They may have inherited kingdoms through female succession, which suggests an unusually high status for women in the tribes at that time in history. And while a lot of the surviving archaeology is similar to other Celtic peoples, they were distinct in one aspect: their stones.

Pictish Stones

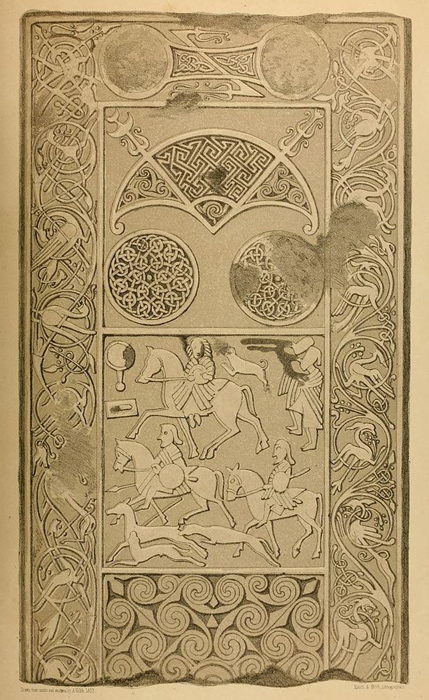

The Picts carved monumental stones with intricate designs and inscriptions. They are the singular surviving evidence of what is was to be distinctly Pictish, and nothing like them has ever been found anywhere else in the British Isles.

Later stones which postdate the Scottish conversion to Christianity retained much of the earlier style and can be seen as analogs to the crosses found elsewhere in Christian kingdoms. This continuation would suggest that the earliest, pagan stones also have a religious function. But what that religion was, and the function of the stones, is almost entirely mysterious.

Archaeologists, baffled by the strange symbols, can only guess. Perhaps the stones were territory markers, although a much simpler and less labor-intensive marker would just as easily serve. Perhaps they were a Pictish language, although if this is the case it is unlikely it will ever be deciphered.

The stones that remain are beautiful in their intricacy and often contain common symbols, such as a crescent moon or common household objects such as a comb. A strange monster is also apparently depicted, perhaps a sea monster of some kind.

But what they were for, is unknown.

What Happened to the Picts?

The later in recorded history we look, the clearer the picture of the Picts can be drawn. And it seems that this group of people, and their unique culture, disappeared within 50 or 60 years amid a period of upheaval and open warfare.

Theories suggest that a new king, Kenneth I, came to rule over the Picts after a brutal Viking attack on the Pictish kingdom of Fortriu in 839 AD. The attack was centered on modern-day Moray, in the northeast of Scotland.

The attack left the king Eóganan mac Óengusa, along with his brother Bran and the King of Dalriada dead. Kenneth swiftly moved to occupy the power vacuum and suppress the remaining Pict culture, seeing the old ways die out.

Kenneth’s maneuver, known as the Treachery of Scone, has become the stuff of the legends. The story of his succession was so transformational and so vivid that it was included in a list of “learned tales” in the 11th Century, part of the oral tradition to be recited at feasts.

According to the legend, the Pictish leadership were invited to a feast where the benches were loose. The loose seats were prepared in that way so that a peg could be drawn from them and the seat would collapse.

At the feast, the Picts were betrayed and the pegs removed so they crashed to the floor. The Pictish leadership were then dispatched, and the new King declared himself at Fortriu. Conquering eastwards from there, he took the fortress at Forteviot and then established his dynasty at Scone.

Kenneth I died in 858. The kingship was passed to his brother Domnall and further, to his son, Constantine I. Kenneth’s descendants still styled themselves “King of the Picts” but much of what made the Pictish culture unique was lost.

What Remains of Their World?

Archaeological excavations of a large fort at Burghead on the Moray coast provide a clearer understanding of the Picts. This site was destroyed in the ninth century, and it is believed that the destruction of this place may reveal their eventual fate.

There is quite some evidence of a slow merging with Gaelic peoples, particularly the western kingdom of the Gaels. The people of the northeast also faced a new threat in the form of the Vikings. Crushed between the two and betrayed by one of their own, these new invaders did what the Romans never could, and extinguished the strange, wonderful world of the Picts.

Top Image: Much of what we know of the Picts comes from their enemies. Source: Iantresman / Public Domain.

By Bipin Dimri