The year was 1971. The New York Times had begun printing the Pentagon Papers: the truth was out about the Vietnam war. The Walt Disney Theme Park opened in Florida, Pakistan and India had gone to war and The Soviet Union sent its first space station into low Earth orbit.

Meanwhile, a pandemic was spreading across the United States, apparently targeting children. Healthy seeming kids were being rushed to emergency rooms across the country in droves, all with one symptom in common: pink poop.

Hospitals were being inundated with parents requesting that their children’s stools be tested. Medical professionals were very worried that this unusual symptom was a sign of rectal bleeding or possibly worse, internal bleeding.

What was happening to these children?

The Stool Study

Recognizing the potential severity of the situation, the Journal of Paediatrics began a study on the strange phenomenon, catchily titled the “Benign Red Pigmentation of Stool Resulting from Food Coloring in a New Breakfast Cereal” case study. They observed the daily life of a twelve-year-old boy who had been admitted to the hospital with pink poop but, after running a battery of tests, physician John V. Payne, who was running the study, was baffled by the inconclusive results.

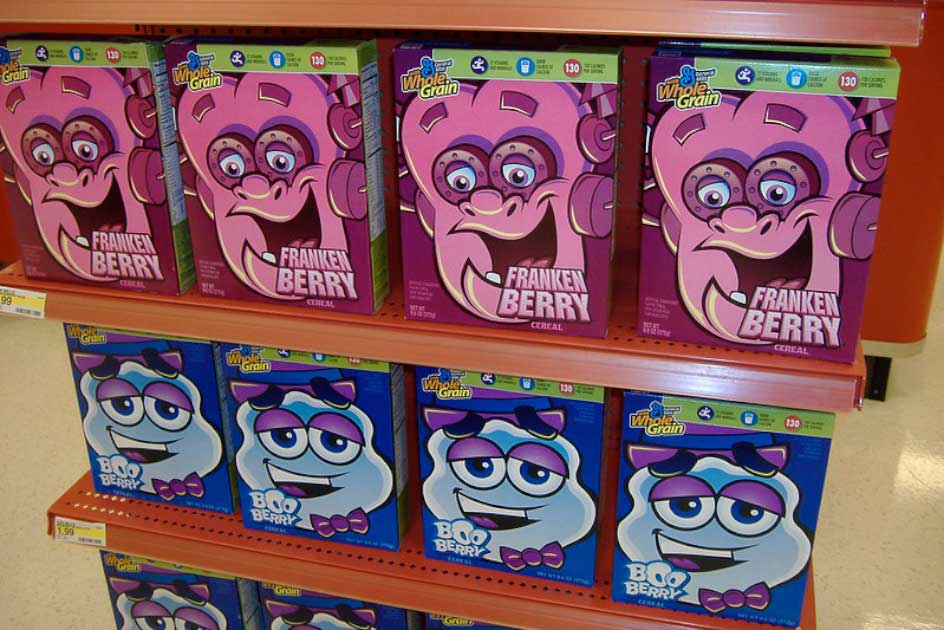

In a last-ditch attempt, they cleared the digestive tract of the boy and then fed him four bowls of popular children’s cereal at the time. “The stool had no abnormal odor but looked like strawberry ice cream,” reported Dr. Payne. The culprit, Franken Berry cereal, was finally apprehended. Upon discovering the study was renamed ‘Franken Berry Stool’.

Once parents’ minds were put at ease that their children weren’t experiencing internal bleeding doctors turned their attention to the question of what had caused the pink-hued poop, and whether it was potentially harmful. General Mills, the manufacturer of the cereal, had been using Red Dye No.2 which was the name given to amaranth, a synthetic food dye. Amaranth was in fact the most commonly used food dye at the time.

- Heroin Cough Medicine? The Rise and Fall of Patent Medicine

- Sending a Message: What was MI6 Doing With All That Semen?

Having only been placed on the market a few weeks earlier, General Mills swiftly switched out Red No. 2 for Red Dye No. 40 in their cereal, in an effort to avoid a public scandal. Evidently, they weren’t the only ones fearing a public backlash.

Mars, the producers of M&M chocolates, removed the red-colored M&Ms for almost ten years. The funny part was that the popular chocolate candies didn’t in fact contain any traces of Red Dye No.2 but in the eyes of the general public, any food dyed red might pose a health hazard so the food company couldn’t take the risk.

That same year in February a Russian study examining the long-term effects of Red Dye No.2 yielded very alarming results. Scientists tested the dye on rats who apparently went on to develop tumors. The FDA dismissed this study as being flawed, though they were not one hundred percent sure that the artificial compound was without potential health risks. Airing on the side of caution, the FDA removed Red Dye No.2 from the list of dyes safe for consumption, effectively banning it.

Another Food Safety Scandal

Since the start of the 20th century, the United States had begun to address the lawlessness in food production and food safety. An eye-opening food study, dubbed “The Poison Squad Trials” revealed many toxic chemicals that were being used in food production, and the FDA had no choice but to address the issue. The “Pure Food and Drug Act” of 1906 saw the first of many sizeable overhauls in food regulations.

The new legislation had banned 80 dyes that were commonly used in the production of confectionaries and edibles, some of which were also being used to dye clothes. Overall, seven colors were given the thumbs up by the FDA as safe to use, and Red Dye No. 2 was one of the seven deemed “safe”.

Evidently they were mistaken, but this was not the first time the 1906 list needed to be revised. The pink poop scandal rang similar to a minor crisis that unfolded on Halloween in 1950, where a number of unsuspecting children fell very ill after eating orange candy containing a mere two percent of FD&C Orange No. 1 food dye.

- The Poison Squad Trials: Do You Know What’s In Your Food?

- The Salem Witch Trials and Ergot: Mushroom Madness?

The following year the FDA was forced to do a complete review of all color additives used in food. After extensive re-evaluation, “The Color Additive Amendments of 1960” provided a guide as to what was deemed as “suitable and safe” for consumption.

Alarmingly about 200 additives that had been in circulation were placed on this list, and were suddenly deemed unsafe. In order to be labeled as safe, they would need to go through more rigorous testing. If the company could not establish that they were harmless they would have to find a safe alternative.

But this was not the first case of a cereal causing the usual color changes in children’s poop. General Mill released Booberry cereal in December 1972, which was colored blue, the same color as the ghost printed on the front of the cereal box.

Booberry used Blue Dye No. 1, a food additive that is currently banned in France, Norway, and Finland. It had the same effect as its red-colored predecessor as it changed consumers’ poop green. The only difference is that green poop doesn’t appear as alarming as red poop,and this is perhaps why it was allowed to pass.

Food Laws: A Work In Progress?

The pink poop scandal was one of a few events that occurred that helped point a finger at the FDA’s loose food safety laws and the need for a massive overhaul. Since then, more strict laws have been put in place around food safety in the USA and now 75% of the die used in cereals today are natural.

However, in Canada and the UK Red Dye No. 2 can still be found in cereals and other confectionaries. Will they ever ban this potentially harmful chemical, or will it take another pink poop pandemic to bring about change?

Top Image: Why did so many children suddenly have pink poop? Source: Tamara / Adobe Stock.

By Roisin Everard