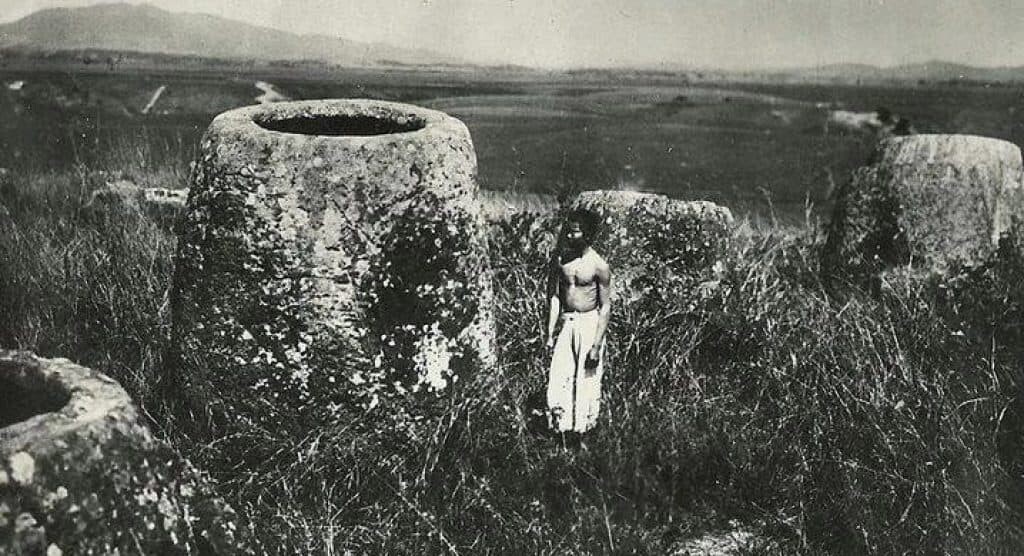

The Plain of Jars is a region of Northern Laos that contains clusters of open-air mortuary vessels of different shapes and sizes. There are more than 2,000 Iron Age jars measuring up to ten feet tall and weighing up to thirty tons. In the cemetery grounds around the jars, experts found burials pits and terracotta urns with human remains and stone discs. Although experts know the area was an ancient mortuary, the specifics about the funerary rituals and what group of people made the burial complex are some of the greatest mysteries in Asia.

Jars Sites

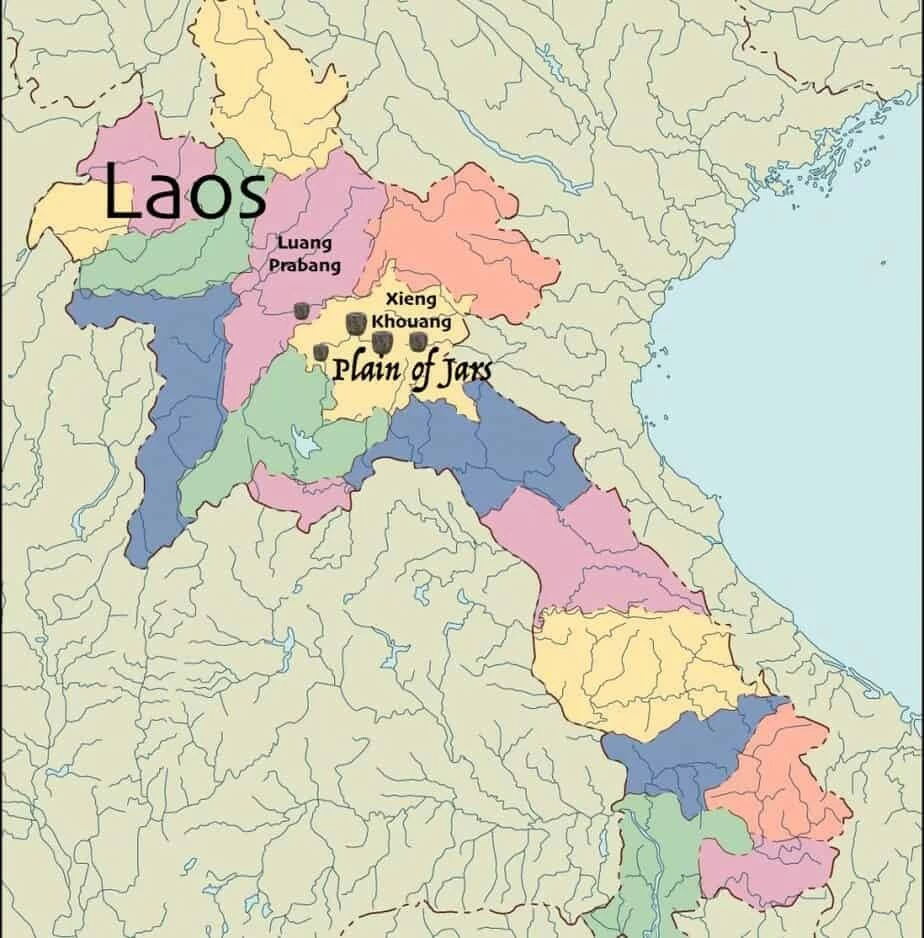

In the early 20th century, the ‘Plain of Jars’ referred specifically to Site 1 (Tong Hai Hin) at Ban Ang in the Xieng Khouang Province. However, since then, archaeologists have discovered and surveyed many other sites to add to the list. In reality, the jars extend into the Luang Prabang province just north of Xieng Khouang. However, none of those sites are open to the public for safety reasons.

There are approximately 90 official jar sites, but in 2014 only eight were open to visitors. The number of sites continues to rise as reports of additional jars surface. Each site contains anywhere between one and more than 400 stone containers. Unfortunately, the majority of sites are off-limits due to dangerous unexploded bombs (UXO) from the Indochina Wars.

Early Work in the Jar Plains

The renowned archaeologist Madeleine Colani of the École française d’Extrême-Orient first investigated the Plain of Jars between 1931-1933. Her research in the field remains the most comprehensive work in existence because she excavated the plains before the area became inundated with bombs during the Vietnam War. In total, Colani surveyed 12 sites in the region and published her findings in her paper, Mégalithes du Haut-Laos, The Megaliths of Upper Laos.

Descriptions of the Jars

The findings of Colani and other modern archaeologists, such as Lia Genovese, have identified many different forms of jars from one district to another. They are all megaliths, consisting of one large stone block carved into various sizes and shapes. Most have one opening on the top and a flat base, however, there are also rare examples of one opening on each end.

The vessels consist of natural rocks, such as limestone, granite, composite, and sandstone. Most of the stones came from local quarries in the surrounding areas. However, some derived from neighboring regions a little farther away.

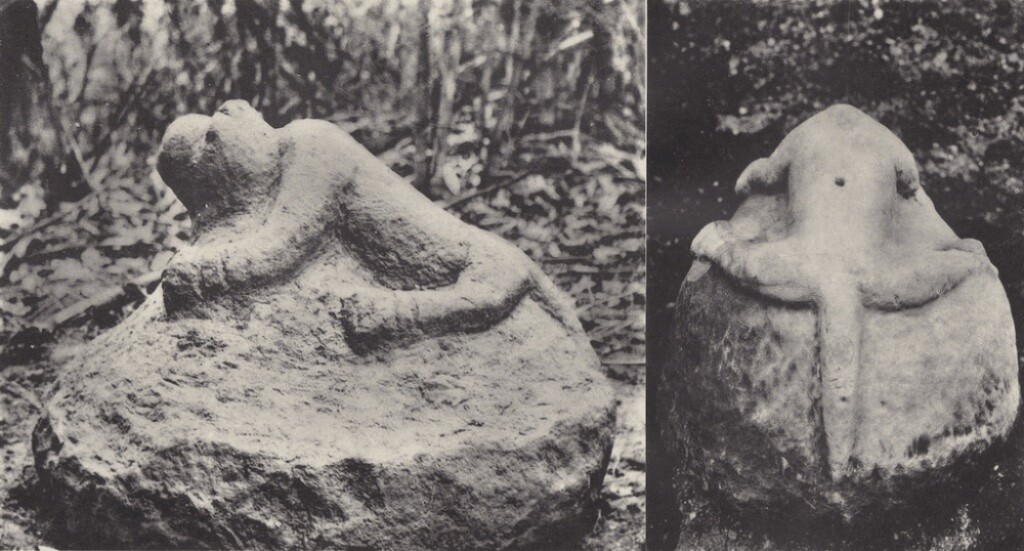

Although flat-top rims prevail, a version with inner rims exists at a few sites. Colani speculated that the inner rims may have supported the placement of a stone lid, however, this is still uncertain. Most jars have a barrel-shaped but there are samples that are more round, squarish, or oblong. Some of the vessels have longer necks. A few have a hole on the side, possibly for the placement of votives or other ritual items. Less commonly, zoomorphic (animal figures) or anthropomorphic (human figures) carvings decorate the lids or sides of the vessels.

Stone Discs and Burial Pits

Archaeologists documented about 200 rather mysterious stone discs around the jar fields. They range in size but are generally no more than three feet wide. Many of them are pancake-shaped, but others are more like button mushrooms. Although most of them are undecorated, some have a pommel or finial on top. A small number of discs exhibit a relief carving of a human, animal, or concentric circles.

Colani argued that the larger discs were not used as lids to the open-air vessels since many of them were not the same size as the jar openings. However, she does mention that the rounder, smaller stones that are buried in the ground are lids to clay burial pots. Eiji Nitta, of Kagoshima University, theorized that the large discs served as landmarks for burial pits.

Sandstone dome with a zoomorphic figure in Luang Prabang. Source: M. Colani. 1935. Mégalithes du Haut-Laos, École Française d’Extrême-Orient, XXV, Paris, vol. 1, pl. 53, 59.

Were There Human Remains?

One important issue that appears to have caused some confusion is whether or not there were human remains discovered in the jars. Lia Genovese is a leading archaeologist from Thammasat University in Thailand. She asserts that “Human remains have not been found inside the stone jars [in Laos], with the exception of ash in a small number of jars at two sites only, although the cremations could have been carried out in recent decades. Bones and teeth have been found inside terracotta pots or in burial pits, buried near the jars and around several of the sites.”

In 2016, an Australian team led by Dougald O’Reilly discovered the first and only primary burial consisting of one entire human skeleton in a ground-grave at Site 1. They estimated the remains to be about 2,500 years old.

Caves for Funerary Uses

Madeleine Colani excavated a cave that she discovered at Site 1 (called Ban Ang). The roof of the cave had two holes that she believed were man-made and possibly served as a chimney. She also found cremated human bone around the cave. Also, at some point, humans made the opening of the cave wider than its original opening. Ultimately, the evidence led Colani to theorize that ancient people had used the cave as a crematorium.

Archaeologists have excavated some other caves in the region within the last ten years, such as the Tham An Mah cave in the Luang Prabang province. Findings reveal human use of the cave possibly as far back as 13,000 BP. It was used as a mortuary since the Iron Age, as evidenced by stone tools and ceramic urns containing human skeletons and other remains. A white disc and boulders directly overlay the burials jars. Within the urns, both cremated and uncremated remains were found. Researchers believe that the same Iron Age people who made the megalithic above-ground jars may have also used the caves for secondary burials.

Importance of the Region

There are various theories about why a mysterious group of people chose this region as funerary grounds. It appears this area held human significance thousands of years before the stone vessels were made. Within the Xieng Khouang and Luang Prabang provinces, a number of caves have indications of human occupation since 13,000 BP. Even more incredible, Laura Shackelton and her team uncovered Southeast Asia’s oldest modern human skull to date in Northern Laos. Dated between 46,000-63,000 years old, this skull indicates that early humans occupied this area earlier than once thought. This doesn’t tell us who created the jars, however, it does tell us that the area has been in use for a very long time.

As history has shown, many civilizations sprung up along important rivers. Laos has the Mekong River which flows from the Tibetan Plateau through Yunnan, China, to Laos, Vietnam, Cambodia, and out to the South China Sea. The Mekong brings with it an abundance of biodiversity, ideal for the ancient hunter-gathers who existed in the region. Later, as people settled down, the river could have additionally provided agrarian farms with water. Inevitably, river settlements would have traded extensively with one another along the route.

Why Did They Choose This Area for Their Mortuary?

- Distance From Large Settlements

There are various theories about the vast expanse of jars, which today is known to make up more than 3,800 square miles (O’Reilly). Interestingly, scientists have not discovered any residential settlements near the jar fields. It may be that the inhabitants of the area chose to keep their dead separated from their settlements. The plains may have been far enough away from their homes yet close enough to transport bodies for funerary rites and burial.

In fact, Colani believed that the Plain of Jars was an intercultural crossroad or a corridor for trade. As such, there may have been large and diverse communities surrounding the area, and the funerary grounds may have served as a separate place for the processing of human bodies in preparation for the after-life.

- Nature and Elevation for Auspicious Burials

The elevation and elements of nature may have made for auspicious burials, as many Asian cultures associate both features with heaven and indwelling gods. While the Southern Chinese had hanging coffin cliff-side burials along the Yangtze, Laos had its vistas from its high mountain plateaus. As the most level spot in the country, the Xieng Khouang central plateaus would have provided stable ground at an elevation of more than 4,000 feet. According to many ancient Southeast Asian cultures, this would have placed the deceased close to heaven and the gods.

[blockquote align=”none” author=”Lia Genovese”]The Plain of Jars may have been a ritually sacred expanse of land with undulating hills, mountain slopes, rivers, spring water stations, abundant sources of stone and, above all, a place associated with ancient burials.[/blockquote]

What Was the Purpose of the Stone Jars?

- Distillation Theory

The mystery of the Plain of Jars is ongoing today. Several scholars, such as Van Den Bergh, R. Engelhardt, and P. Rogers propose the “distillation” theory that appears to have widespread appeal. In this case, the large containers would have stored the human bodies in the first stage of decomposition. This would have given the spirit time to leave the body. Then once the soul had sufficiently departed, the body would be cremated and the remains buried in clay pots in the ground.

A counter-argument against this theory indicates that many of the stone containers did not have internal areas large enough to contain a whole human body. What then did the people do with the jars that had small openings? Van Den Bergh argues that the megaliths appear to have undergone different phases of usage throughout the centuries, as the culture shifted away from distillation to cremation.

- Local Legends

Locals have their own legends about the history of the area. One story involves giants who once inhabited the land and used the massive containers for drinking. Another legend says the vessels were fermentation vats for a large amount of rice wine used for feasts.

Who Created the Funerary Sites?

There is uncertainty about the creators of the Plain of Jars. The people who inhabit the region today have only been there about a thousand years. Their descendants, the Tai group, began migrating into the area from Southern China around 500 CE. Some experts assert that the Tai people replaced earlier Austroasiatic people who may have created the vessels.

Archaeologists found similar stone vessels in Assam, India, and in Indonesia. This suggests that perhaps a wave of proto-Malays traveled through India and into Northern Laos. However, more research on the settlements around the area is necessary. Unfortunately, much of the land is too dangerous to explore.

Bombs in the Fields

As noted, a large amount of unexploded ordnance (UXO) blankets the area and hinders excavations. The bombing was an effort by the U.S. to thwart the movement along the Ho Chi Minh Trail during the Vietnam War. The National Regulatory Agency indicates that between 1964 and 1973, the U.S. dropped more than 200 million tons of ordnance on Laos. This included 270 million cluster bombs, of which about 30 percent are unexploded.

You May Also Like: Angkor Wat: The Enduring Pride of the Khmer Empire

Meanwhile, the jars and other ancient artifacts that survived the bombings are continually facing damage. The elements, farming, and vandalism by locals and tourists take their toll. Additionally, the development and the usage of vessels for various domestic purposes have disrupted the sites.

Mysteries Endure

The incredible Plain of Jars is a testament to an ancient and mysterious culture with spiritual and funerary beliefs that we are only beginning to understand. More research is essential to unlocking the enigmas of who created the fields of cemeteries and how did they use the stone vessels? Meanwhile, there are efforts by the Laotian government and UNESCO to protect this unique and rich archaeological site from further damage.

Additional references:

Genovese, Lia. Academia. 2016. Accessed March 28, 2017.

Roberts, Nicholas. “The Cultural and Natural Heritage of Caves in the Lao PDR: Prospects and Challenges Related to Their Use, Management and Conservation.” The Journal for Lao Studies, 2015, 120. Accessed March 28, 2017.

Featured social media image credit: Carrie Kellenberger.