Robert Prager was a man who found himself in the wrong place at the wrong time. An inhabitant of Collinsville, Illinois, he doubtless felt himself to be far away from the terrible destruction wrought on the other side of the Atlantic by World War I.

But he was mistaken, as a a chilling incident which occurred on April 5, 1918, would demonstrate as it cast a sinister shadow on the American Homefront. Prager, a German immigrant, and coal miner, fell prey to the unchecked aggressions fueled by wartime hysteria and anti-German sentiment.

His story, encapsulated in the tragic events that transpired that fateful day, serves as a haunting reminder of the darker side of nationalism and the perilous consequences of unfounded suspicions.

Who was Robert Prager?

Prager was born in Dresden, Germany on February 28, 1888, but moved to the United States in 1905 when he was just 17 years old. By the time the United States had joined the war against Germany in 1917, he was living in St. Louis, Missouri.

Prager showed early on whose side he was on and started efforts to become an American citizen the day after Woodrow Wilson’s war speech on April 2, 1917. He then signed up for the draft with the hopes of joining the Navy. A patriot to his adopted country, he liked to display an American flag in his window, going as far as to report his landlord to the police when he objected.

Unfortunately for Prager, the Navy rejected him due to medical reasons. For much of 1917, he then moved around Missouri and Illinois looking for work.

Towards the end of summer, he ended up in Collinsville, a mining town in southern Illinois. At first, he worked as a baker for a fellow immigrant, Lorenzo Bruno, but soon learned he could be earning much more as a miner.

He began working as a laborer at the Donk Brother Coal and Coke Co. and decided to apply for full membership as a mine worker in the United Mine Workers of America Local 1802 union. In recent years, the miners’ unions in the area had become increasingly radicalized and quick to turn to violence after there had been little official resistance to recent strikes.

There was also a lot of social tension at play. The hiring of black and “imported workers” in the region had led to the East St Louis Race Riots in early 1917. All of this, plus the fact that Prager was a socialist by conviction, meant that his application to join the union was declined. His reaction to this injustice would lead to his death.

The Hunt for Prager

Things started going wrong for Prager on April 3, 1918. At that night’s union meeting his application to join was rejected and the miners paraded the poor man near Maryville’s saloons. He was then “warned” to leave town.

Unfortunately, Prager had an argumentative personality and wasn’t ready to take this lying down. The next day he wrote a letter to the miners complaining that he’d been treated unfairly by their leader, President James Fornero.

In the letter, he declared he had never been a scab (striker breaker) and that he was the “heart and soul for the good old USA. I am of German birth; of which accident I cannot help.” He posted his letter around the town’s mines and saloons.

That was his next mistake. The miners reacted poorly to receiving Prager’s letter and things quickly got out of hand. Initially a group of around six men headed to Prager’s home on Candlia Street, the group growing with each saloon it passed.

At around 9.45 pm dozens of men turned up at Prager’s door. Prager was told to come out and kiss the flag to prove his patriotism. Prager agreed. He was then told to take his shoes off, and barefoot, he was wrapped in the flag and paraded along Main Street in Collinsville. The mob began to snowball, and it soon numbered around 300 men.

At 10 pm the police became involved. Three policemen managed to take Prager from the mob and lock him up in jail for his safety in the basement of City Hall. He didn’t remain safe for long.

The mob, enraged by the police’s interference, congregated outside City Hall. The city’s mayor, John H. Siegel, then tried to calm the mob down by urging them to let federal authorities deal with the German. Appealing to the mob’s intelligence they pointed out that if he really was a spy, he might have intel the government could use.

The mob refused to listen and instead began attacking the officials, accusing them of being pro-German traitors too. While this was going on the police were trying to find a way to sneak Prager out. Sadly, there was no escape and they settled on hiding him.

At the same time, the mayor told the mob that Prager had been taken away by federal authorities. The mob, evidently not as stupid as they looked, didn’t believe him and insisted on searching City Hall. Prager was quickly found and carried back out to the mob.

As the mob marched along Main Street and St. Louis Road, Prager was forced to sing patriotic songs and kiss the flag. Upon arriving at the top of Bluff Hill, which overlooks St. Louis, the mob decided to tar and feather Prager.

When they failed to find enough tar 28-year-old Joe Reigel (who was also of German descent) pulled out some rope and suggested they hang Prager. His companions were initially reluctant, but no one was brave enough to speak up. Prager was lynched in front of 100-200 men (and some women) at 12.30 am, April 5, 1918.

Why Prager?

It’d be easy to single out the mob and lay all the blame on them, but in truth, the American government deserved a fair share of the blame. When the First World War broke out in Europe in 1914 much of America held a deeply Isolationist viewpoint.

- The Murder of Mabel de Belleme, Arch Schemer of the Norman Conquest

- The Osage Indian Murders: Oklahoma’s Reign of Terror

For many, the war was a European problem, not an American one. This view was echoed by the country’s anarchists and socialists, who were against the US joining the war in favor of focusing on domestic issues like economic inequality and labor rights.

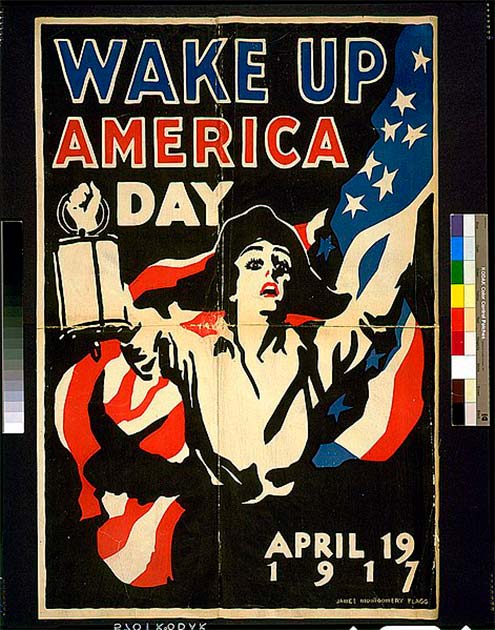

However, the US government wanted to join the war effort and needed to sway public opinion. This led to the Committee on Public Information (CPI) releasing a massive propaganda campaign to increase patriotic support for the war. Newspapers and magazines were flooded with pro-war propaganda and the streets were plastered with patriotic posters.

At the same time, Congress passed the Espionage Act of 1917. The government wielded this as a weapon against anarchist and socialist groups who were still largely anti-war (as well as being opposed to the government in general).

This all added up to a climate of fear in deeply patriotic areas like Collinsville. The propaganda released by the government urged people to be on high alert for enemy spies.

Soon any European immigrant was a threat. A statement released in the Collinsville Advertiser perhaps sums this climate up best: “Every German or Austrian in the United States, unless known by years of association to be absolutely loyal, should be treated as a potential spy,”.

No Justice

On April 25, 1917, five men, including Joe Riegel, were indicted for Prager’s lynching, their trial began on May 13. Anti-immigrant opinion was so ingrained in the area that attorneys had to review over 700 prospective jurors before the trial could even get underway. The judge, hoping to get Prager justice, banned the defense from claiming Prager was disloyal.

It was all for naught. The trial lasted for five days with the jury’s deliberations only taking ten minutes. All defendants were found innocent, despite the fact Riegel had confessed to everything when questioned by the police.

The local paper the Collinsville Herald celebrated with an editorial that said, “The community is well convinced that he was disloyal…. The city does not miss him. The lesson of his death has had a wholesome effect on the Germanists of Collinsville and the rest of the nation.”

Nationally the attitude was more measured with papers like the New York Times condemning what had happened to Prager and pointing out the dangers of “mob justice.” In subsequent years, efforts were made to memorialize Robert Prager and ensure that his death was not forgotten.

The national discourse surrounding the lynching contributed to a broader awareness of the dangers posed by unchecked aggression, urging communities to confront their own biases and prejudices. The legacy of Robert Prager’s tragic death became a haunting reminder of the fragility of justice and the imperative of guarding against the corrosive influence of unchecked hatred.

Top Image: Robert Orager was murdered for who he was, rather than anything he had done. Source: Zef Art / Adobe Stock.